Biography

Celebrated for her artistic contributions to the pulp fiction industry during the 1940s, Gloria Stoll Karn (b. 1923) was one of very few female illustrators working to create a steady stream of tantalizing images for the covers of popular romance and dime store magazines. During the first half of the twentieth century, inexpensive fiction magazines were described as “the pulps” for the wood pulp paper that they were printed on, in contrast to the glossies or “slicks” like The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, and Harper’s, which were published on higher quality stock. Sensational subjects—from romance and westerns to crime and detective stories—were popular fare for the genre, which was enjoyed by millions for its captivating entertainment value.

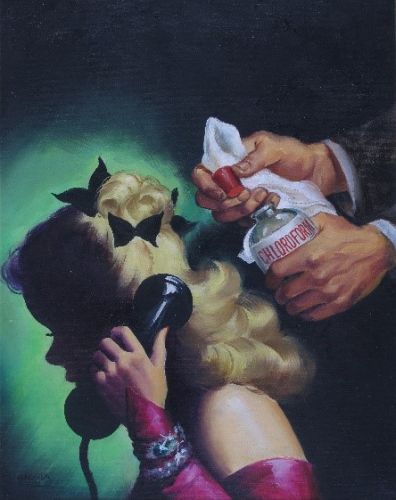

Fig. 1. Gloria Stoll Karn, Cover illustration for Detective Tales, July 1945

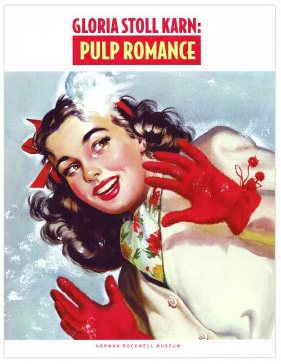

From 1941 to 1949, Stoll Karn’s vibrant, sometimes provocative illustrations were highly sought after by Popular Publications, one of the largest publishers of pulp magazines, and her work appeared regularly in issues of Black Mask, Dime Mystery, Detective Tales, New Detective, All-Story Love, New Love, Love Book, Love Short Stories, Love Novels, Romance, and Thrilling Love, as well Argosy. At the time, female illustrators more frequently worked in educational publishing, or created illustrations focused on domesticity and themes relating to childhood or motherhood. Gloria Stoll Karn: Pulp Romance, a Norman Rockwell Museum exhibition scheduled to be on view from February 10 through June 10 2018, explores the illustrator’s prolific, nearly decade-long career, and her unexpected journey in a world previously assigned to male artists.

The child of Charles and Anne Stoll, both artists, Stoll Karn was born in the Bronx, New York, and grew up in the borough of Queens. Her earliest aesthetic lessons were derived from her father, a designer and illustrator who gently critiqued her youthful drawings for their accuracy and adherence to the conventions of artistic technique. In describing the use of contour, light, and shadow to describe form, “he reminded me that the lightest lights and the darkest darks never appears on the edge of an object,” she said. “I always remembered that, and it's so true, because even the darkest side of an object has some reflected light coming from its surroundings.”

During her teenage years at the newly-established High School of Music and Art, Stoll Karn established fond memories and developed a strong portfolio, hoping to forge a career in the field. However, her father’s untimely death at the age of 45, when she was just 15, and the urgency to earn an income, almost caused her to change course. After graduation, hoping to assist her mother in supporting their household, she sought employment as an artist, but became discouraged when assignments did not materialize. To shore up her finances, she obtained an office job at New York Life Insurance Company, where did secretarial work and filed informational cards on the company’s clients. Eventually, she was promoted from filer to puller, “so I removed the cards then, and there were just endless rows of steel filing cabinets. I can remember looking at the clock and watching the second hand go around,” she said.

Fig. 2. Gloria Stoll Karn, 1941

Sure that a career in the arts would not be realized, Stoll Karn decided to free up space in the small apartment that she shared with her mother by burning her art portfolio in in her Queens building incinerator. Too large to fit down the chute, she left her work on the floor, awaiting trash removal. Thankfully, a knock on her door by the building’s handyman the next morning revealed that her art was still intact—he had taken the time to leaf through her work and share it with famous pulp illustrator Rafael DeSoto (1904-1992), who was also a building resident. Impressed by what he saw, DeSoto referred Stoll Karn to Popular Publications, and the steady stream of assignments that followed allowed her to establish a thriving freelance career.

“I was still working for the insurance company when he got me a story to illustrate,” Stoll Karn remembered. “We were not supposed to leave the company at lunch or anytime, so I snuck out of the building and took the subway up to 42nd Street to deliver the illustration. I was seated in the editor's office, and after a while, the secretary who had delivered my piece to the art director came back saying, "Well, Alex said 'we've had worse.'" Thinking that her career had been launched, Stoll Karn wondered about the implication of this statement, and was concerned that this might be her last opportunity to publish her art, “ but low and behold, sure enough, I did,” she said. “I got another illustration to do, and then another, and another, and another. That's how I got started.”

Just seventeen when she met DeSoto, Stoll Karn found the more established artist to be an important mentor—he willingly shared background on painting techniques and the publishing business, and encouraged her to continue drawing from the model to enhance her knowledge of the figure. While earning her living as an illustrator, she attended evening classes at the Art Students League, where Norman Rockwell had received training decades before, studying anatomy, etching, painting, and lithography. Noted Golden Age illustrator Harvey Dunn (1884-1952), who had been a student of Howard Pyle (1853-1911) and classmate of N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945), was one of her most highly regarded teachers.

Fig. 3. Gloria Stoll Karn, 1945

When creating her compositions, Stoll Karn sought visual reference for her work at the famed Picture Collection at the New York Public Library, then housed at the Mid-Mahattan Branch. There, images on every subject, from animals to appliances, could be referenced and checked out for review. “Then I started my own—I used to call it the morgue. It was my own collection of pictures from magazines, and of course, Rafael DeSoto had a big assortment, so I had access to that as well.” Stoll Karn created a studio in her bedroom at home and secured work space with DeSoto in a well-lit sixth floor studio at 28 West 65th Street in Manhattan. She later rented an apartment that became her studio in Brooklyn Heights, where she managed to cook and entertain without the benefit of a kitchen. “I would have dinner parties, small ones. It just served my purpose and was very, very nice. Those were years of maturing and I needed to be on my own.”

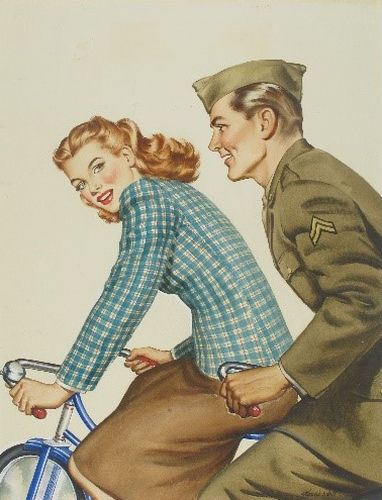

Boy meets girl themes envisioned with a touch of humor were Stoll Karn’s specialty, and the most popular scenarios in pulp magazines. Steamy portrayals of couples in embrace, gallant soldiers and cowboys, and hardboiled detectives and scoundrels—male and female—kept the artist and her readers consistently entertained. To stand out on the newsstand, Stoll Karn’s images were colorful and clearly delineated, with idyllic, animated figures dominating the picture plane. “I love to do hands and I love to paint hair—those are the two things I like to do best,” said the artist, who appreciated their expressive potential. “The anatomy of the hand is interesting, and it's actually simple once you get the feeling for it.” Models appearing in the artist’s cover illustrations were often professionals hired from New York agencies, but her friends and beaus also made regular appearances in her art.

Fig. 4. Gloria Stoll Karn, Cover illustration for All-Story Love, November 1945

Fig. 5. Gloria Stoll Karn, Cover illustration for Rangeland Romances, February 1945

When creating cover concepts, Stoll Karn generally presented three sketches for review. “They had to be approved by Harry Steeger, who was the CEO and co-founder of Popular Publications. He would gently choose one of the three to bring to a finish, but I would save the other two for a while and resubmit them later on. Many were eventually accepted because they were good ideas.” Artists working for Popular Publications developed cover concepts designed to communicate the flavor of each magazine without having to specifically reference the stories inside. For Stoll Karn, who was about 18 years old when she began creating covers, “romantic ideas were very easy to come by. I used to love the 1940s movies, where boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl. Those films were a big influence on my subject matter—I think I learned more from the movies than from real life at that time.” “I could see where romantic ideas would naturally come to a young girl, but where did the more gruesome ideas for cover illustrations come from? I guess I realized that people have a shadowy side. I think we all do, and that was my way of expressing it.”

Fig. 6. Fred Karn and Gloria Stoll Karn, 1942

Though she relished her nearly decade-long career as a pulp illustrator, the artist’s life took a different turn in 1949 when she married Fred Karn, whom she met at a party given by Rafael DeSoto. A chemist by profession, Karn found employment as a scientist at the Bureau of Mines in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where the couple would settle and raise three children in a home that they designed and built. Though her last pulp cover was published that year, she continued to create art for personal enjoyment. In Pittsburgh, Stoll Karn attended classes at Carnegie Mellon University, and taught painting and collage at the Community College of Allegheny County, The Sweetwater Center for the Arts, and the North Hills Art Center. Now in her nineties, Stoll Karn still reaps the rewards of a creative life and continues to explore a range of techniques and styles in her art which bring satisfaction.

Stephanie Haboush Plunkett

With sincere thanks to Jeanne Torlidas Willow

Fig. 6. Gloria Stoll Karn, 2017

Purchase the Gloria Stoll Karn: Pulp Romance Exhibition Catalog here...

Illustrations by Gloria Stoll Karn

Additional Resources

Bibliography

Ellis, Douglas, Ed Hulse, and Robert Weinberg. The Art of the Pulps: An Illustrated History. San Diego, CA: IDW Publishing, October 24, 2017.

_60_60_c1.jpg)

_60_60_c1.jpg)