Biography

Becoming an Artist

Born in Brooklyn, New York in 1927, Mort Künstler showed an innate talent for art as a child, and was encouraged by his father, Tom Künstler, to explore and pursue a love of drawing. He purchased art supplies for his son long before he began his formal education, setting up still-life arrangements and instructing him to “paint what you see.” Elementary school teachers at Brooklyn’s Public School 215 took note of Künstler’s burgeoning skill, and with the support of his mother Rebecca, he enrolled in art classes at the Brooklyn Museum. This youthful art school experience, which provided access to the collections of a world-class museum, exposed him to a wide variety of artists and established a love and appreciation of art.

At this time, Künstler began developing health problems. Though frustrating, his time in bed afforded him ample opportunity to develop his drawing skills. To help him regain his strength, his father proscribed a course of athletics to follow. Although the family’s resources were limited, he provided his son with basketballs, bats, and baseballs to increase his physical stamina, while simultaneously, Künstler continued to develop his keen sense of composition.

Tom Künstler, an Amoco salesman, also brought Mort on visits with his friend Dave Gross, an artist who worked with his sons George Gross and Arthur Gross in the field of commercial illustration. “By watching these men as artists, I developed an appreciation for how they worked, what art was like as a business.” Künstler acknowledges how much this exposure and experience shaped him as an artist. The Gross family encouraged and critiqued his early work, and he took their advice to heart, more determined than ever to move forward as an artist.

At Abraham Lincoln High School in Brooklyn, Künstler was no longer the sickly boy of his youth, as he excelled as an athlete, particularly in diving and basketball. His high school art teacher, Leon Friend, author of the book Graphic Design, offered much inspiration, encouraging Künstler to think abstractly when painting and to consider attending art school to extend his studies. In 1943, at just fifteen years of age, Künstler graduated from high school and enrolled at Brooklyn College, where he excelled in athletics, becoming a four sport letterman. His focus on sports left little time for his art at that time, and he attended University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) on a basketball scholarship, until the sudden decline of his father’s health prompted his return home. After spending time assisting his father, Künstler enrolled in art school at Pratt Institute, an opportunity made possible by former Brooklyn College coach, Artie Musicant, who secured a basketball scholarship for him there.

In 1949, Künstler and a fellow Pratt student set out on a summer excursion to Mexico City, outfitting a pair of bicycles with personal effects and art supplies to paint and draw the Mexican countryside. Splitting up after a month together, Künstler spent the rest of the trip biking and painting with the goal of producing a picture each day. Künstler looks back on this period of his life with fondness, for being alone required him to be self-reliant, learn the Spanish language, and become adept as a watercolorist, all while working in an unfamiliar environment.

Early Career

After graduating from Pratt Institute, Künstler was hired by Bill Neeley, owner of Neeley Associates, a fast-paced New York illustration studio. Hired to clean the studio and do prep work for the other artists, Künstler used this time to pepper the studio’s artists with questions about their assignments, absorbing as much as he could by watching the illustrators work. “In those days,” he recalled, “there were illustration studios that would provide space and materials, and sales people who would sell the work on a commission basis. The fees were split fifty-fifty between the artist and the company.” Eventually responsible for making necessary changes to finished assignments, he also began creating his own imagery to build experience. Künstler recalled a bit of advice that popular illustrator Mac Conner gave him at the time. “Figure it out for yourself,” Conner said, ”We all use the same models, we all have projectors, we all have the same brushes, the same paints. What is the difference between one illustrator and another? Why does one get the work and why doesn’t another? The big difference is up here,” Conner emphasized, pointing to his head, “as well as here,” holding out his hand. “And that was a great lesson,” Künstler said. “I learned a lot from that, and would only add that one must also listen to their heart.”

After three months at Neeley Associates, Künstler left the studio to pursue freelance illustration, bringing his portfolio around to potential clients to secure work for himself. Rapidly gaining assignments, he produced book jackets for paperbacks and illustrated stories for popular men’s adventure magazines. During this time, he worked with and shared studio space with his childhood idol, George Gross, whose art was in demand by publishers of pulp magazines and paperback books. Gross took time to discuss the art of Golden Age illustrators J.C. Leyendecker, N.C Wyeth, and Norman Rockwell with Künstler, holding them up as examples of how to compose particular subjects and use light and shadow effectively in an artwork—commentary that would be taken to heart and reflected in Künstler’s own compositions.

Practiced Professional

By the mid-1950s, Künstler had become a skilled and experienced artist who was receiving commissions from many of the most prominent publications of the day. Sports Afield, Boys’ Life, The Saturday Evening Post, Outdoor Life, and True Magazine published his work regularly, and Men’s Adventure, a frequent client, offered both artistic challenge and financial rewards. His dynamic illustrations, focusing on themes of man’s encounters with nature, criminals and mobsters, damsels in distress, espionage, and military conflicts were gripping, rich in detail, and immensely popular.

As the 1950s progressed, Künstler understood that photography and television were starting to change the landscape of the illustration business. A relatively new medium at the time, television began replacing publications as the primary focus of advertising dollars, and photography, which conveyed a greater sense of immediacy in a rapidly changing world, stood in more frequently for illustration. The loss of revenue and audience prompted many magazines to change direction or fold entirely, and Künstler realized that his illustrations had to provide something that the camera could not. His dramatic compositions and theatrical scenarios portrayed stories in a way that could have not possibly been captured by photography, and he determined to create illustrations in a visually exciting and richly detailed way. Working constantly, as much as fifteen to sixteen hours a day, Künstler honed his vision and his skills, and cites long hours of work as instrumental in developing his technique and style.

In 1961, Künstler moved to Mexico in the hope of providing his wife Deborah Künstler, who modeled for many of his paintings, and their children David, Amy, and Jane with a unique cultural and educational experience. While in Mexico, Künstler continued producing art for Magazine Management, a company that published and circulated men’s adventure, humor, and lifestyle magazines of the day. Magazine Management was also the parent company of Marvel Comics, which famously hired writer Stan Lee to run its comics division, and eventually became known as Marvel Entertainment. Künstler continued to “paint what was in front of him,” as his father had advised, but he also created imaginative visual fantasies that engaged his many readers and fans. “I liked making pictures for stories that were believable, and I did paint pictures for a lot of stories that were unbelievable. I think those were the most difficult, but I tried to make those pictures look real, too,” he said.

Returning to the United States in 1963, Künstler settled his family in Oyster Bay, New York, a scenic town on the Long Island Sound, and continued to work with Magazine Management. The company’s talented stable of writers included Mario Puzo; Künstler would later illustrate the first depictions of the Corleone family in The Godfather. Always seeking new outlets for his art, he discovered a new arena for his work—the model kit market. His interest in historical accuracy dovetailed nicely with the needs of model manufactures that required striking, detailed images illustrating the contents of their kits featuring classic aircraft, automobiles, and World War II themed subjects.

Artist and Historian

A 1966 assignment for National Geographic depicting the early history of St. Augustine, Florida, introduced Künstler to the deep and comprehensive research needed to render a historically accurate scene. A later assignment about the discovery of San Francisco Bay fully exposed him to National Geographic’s scientific and historical subjects and their methodology for producing articles about non-fiction subjects. Consulting with historians and experts in the field, Künstler embraced this method of working, and would continue to use historical research, often combined with site visits, to produce his imagery.

With the demise of many men’s adventure magazines in the 1970s, Künstler began to take on assignments for Newsweek and Good Housekeeping, and create advertising art for national brands like Solarcaine, Old Crow Whiskey, and NYNEX. His eye-catching advertisements led to projects for major film studios, and he painted theatrical movie poster illustrations for such classic disaster films as The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and The Hindenburg (1975), and action movies like Go Tell the Spartans (1978), The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974), and the cult favorite, The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1974).

Commissions from Blair Galleries in Santa Fe, New Mexico were among the first that Künstler accepted for artworks not intended for publication, shifting his focus from published illustration to gallery painting. Künstler created his first painting to be produced as a limited edition print in 1976, using the research skills that he acquired as an illustrator in Stroud Farm, a lyrical work that drew inspiration from site visits to the wheat fields of Kansas and Nebraska. That year, he also produced a satirical cover for the iconic and irreverent humor magazine, MAD, adding his distinctive spin to the popular poster for Jaws under the alias “Mutz.”

On the advice of long-time friend, James Bama, a successful illustrator who turned to painting Western themes, Künstler too began selling his Western subjects in galleries. Brisk sales of art inspired by the American West and Native Americans of the Northwest Coast attested to their appeal, inspiring him to continue down this path. Long-standing relationships with the Kennedy and Hammer Galleries in New York have been testaments to his success. Always seeking new challenges, Künstler was commissioned by the Rockwell International Corporation to capture the 1981 launch of the Space Shuttle Columbia, providing unexpected viewpoints that would have been difficult to access without the vision of a skilled and creative artist.

Reimagining the American Civil War

Künstler’s depictions of the American Civil War have decidedly established his legacy as an outstanding visual historian. In 1981, he accepted his last advertising commission as an illustrator in order to turn his full attention to his work as a painter of historical subjects. In 1982, Künstler completed the painting that would become the official logo for the CBS mini-series, The Blue and the Gray. His personal interest in the American Civil War and the positive reaction that his artwork garnered inspired Künstler to continue his focus on the period. His meticulous, expressive paintings highlight chaos, battle, and poignant moments of intimacy against the backdrop of the most traumatic and bloody conflict the nation had ever endured.

Absolution Before Victory: The Irish Brigade at Antietam, September 17, 1862 portrays a moment that is both fleeting and moving. In the image, the Irish Brigade is about to engage the enemy at the Battle of Antietam. As they are about to move forward, a priest turns his horse to bless his charges before moving on, a moving image that highlight the faith, courage and devotion that these soldiers displayed. Success as a Civil War painter has established Künstler as one the preeminent historical artists in the world. Sought after by collectors and publishers, he has exhibited his art in museums and at historical sites throughout the United States, and has earned recognition from prominent scholars in the field.

Continuing his work with great dedication, and maintaining an intensive schedule by any standard, Künstler continues to create popular illustrative artwork that brings together his passion for historical research and vast artistic abilities to current subjects and projects. Recent depictions of the American Revolution offer the opportunity for immersion in another time period, and a new series of works for Maximus Vodka bring him back to his roots as an illustrator of adventure stories. “I think I’ve got the best job in the world, because if I were retired, I would still want to paint pictures,” Künstler said, reflecting upon his prolific six-decade career. “What more could you want than to have people look at your work and enjoy it?” he said, showing no interest in slowing down any time soon.

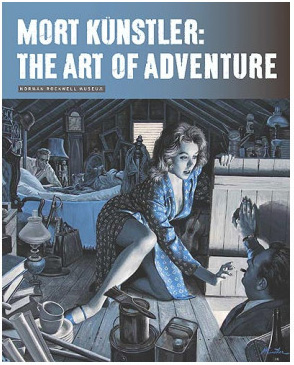

Purchase the Mort Kunstler: The Art of Adventure: Exhibition Catalog here...

Illustrations by Mort Künstler

Additional Resources

- Yesterday’s Papers

- The Paperback Palette

- Mort Kunstler: The Art of Adventure

- “Mort Künstler: The Art of Adventure”

- “The Illustrator in America, 1860-2000,” by Walt Reed

Bibliography

Künstler, Mort. The Civil War Paintings of Mort Künstler. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House, 2006.

Künstler, Mort. Mort Künstler's Civil War: The South. Nashville, TN: Rutledge Hill Press, 1997.

Künstler, Mort and Dee Brown. Images of the Old West. New York: Park Lane Press, 1996.

Künstler, Mort and James I. Robertson. Gods and Generals: The Paintings of Mort Künstler. Shelton, CT: Greenwich Workshop Press, 2002.

Künstler, Mort and James I. Robertson. Mort Künstler's Old West: Cowboys. Nashville, TN: Rutledge Hill Press, 1998.

Parfrey, Adam. It’s A Man’s World: Men’s Adventure Magazines, The Postwar Pulps. Los Angeles, CA: Feral House, 2003.

_60_60_c1.jpg)