Biography

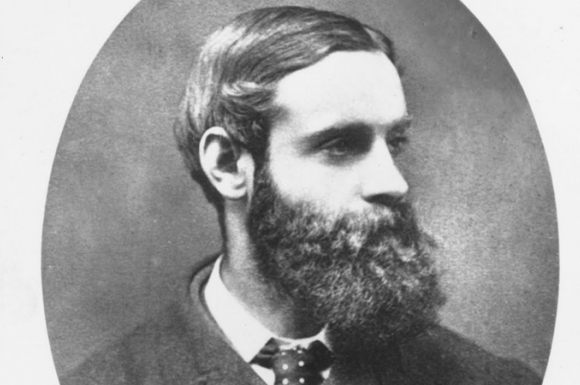

Randolph Caldecott (1846-1886) was born to John and Mary Dinah Caldecott in Chester, Cheshire, England on March 22, 1846. As a child, Caldecott attended school in Chester and frequently drew animals and painted in oils, and even created a small portrait of his brother, Alfred. Caldecott contracted rheumatic fever which permanently affected his heart. Like Edward Lear, he continued to suffer with poor health for the rest of his life, frequently traveling to continental Europe to escape the cold, damp conditions of England. When he was fifteen, Caldecott left school and moved to Whitchurch, Cheshire where he worked for the Whitchurch & Ellesmere Bank, a logical step for the son of an accountant. While living in Whitchurch, Caldecott took up hunting as an extension of his love of horseback riding. This hobby proved useful as he made many sketches of hunting scenes and the local scenery in that part of Cheshire which he would later incorporate into his illustrations. In 1861, the same year that Caldecott left school, his first drawing was published in Illustrated London News. The image that was published was a sketch of a disastrous fire at the Queen Railway Hotel in Chester, which accompanied Caldecott’s written account of the event. After spending six years in Whitchurch, Caldecott moved to Manchester to work at the head office of Manchester & Salford Bank. While living in Manchester, Caldecott began attending night school at the Manchester School of Art. Manchester was a new experience for Caldecott because it was a larger city with many more opportunities for him to develop his artistic skills; while living there, he contributed to local papers and even a few London publications with some success. By 1869, one of Caldecott’s pictures was hung in the Royal Manchester Institute, a symbol of his imminent success.

In 1870, while still living in Manchester, Randolph Caldecott was put in touch with Henry Blackburn, the art editor for London Society, a popular magazine. Blackburn published a number of Caldecott’s drawings in several issues of his magazine, eventually becoming a close friend of the illustrator. By 1872, at the age of twenty-six, Caldecott quit his job at the bank and moved to London to pursue a full-time career in art. After years of contributing to publications with success, and friends insisting that he could sustain himself in an artistic career, Caldecott took the plunge and became a successful magazine illustrator within two years. Working on commission, Caldecott was creating individual sketches, illustrations of written articles, and a series of illustrations based on a holiday in the Hartz Mountains with Blackburn. This series was actually the first of many due to its popularity in the publication. Caldecott lived in London for seven years, and while there made many eminent acquaintances, such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, George du Maurier (a fellow contributor to Punch magazine), John Everett Millais, and Sir Frederic Leighton. Caldecott’s friendship with Leighton also connected him to Walter Crane, who became both a friend and a professional rival.

Caldecott’s relation to Crane also arose in his partnership with Edmund Evans, the color printer and famed engraver who had worked with Crane throughout the early years of his career. In 1877, Evans contacted Caldecott about taking over for Walter Crane as his lead illustrator, working on two books for Christmas, The House that Jack Built (Crane’s preeminent debut work) and The Diverting History of John Gilpin. Published for Christmas 1878, Caldecott’s first children’s books were an immediate success. He enjoyed illustrating them so much that he continued to finish two per year for the next eight years until his death. Caldecott chose the stories and rhymes that he illustrated, often altering, and in some cases writing or rewriting the text himself. Eventually, Caldecott illustrated two books for Washington Irving, three for Juliana Ewing, another for Henry Blackburn, one for Captain Frederick Maryatt, and several for other authors. Unlike Walter Crane, who accepted a one-time payment for each of the books he illustrated for Edmund Evans (meaning that he did not financially benefit from any of the sales of his books created for the publisher), Caldecott refused to agree to a contract that stated he would not receive royalties from his books, and eventually reached an agreement with Evans that he would receive a small portion of the one-shilling price for each book.

Randolph Caldecott was familiar with Walter Crane’s work for Edmund Evans and thought it too static and lifeless. Crane was known for his very Romantic and decorative prints, filling the entire page with flowing decoration that complemented his regal figures. Knowing that he could not, and did not want to replicate Crane’s style, Caldecott told Evans that he could not expect the same type of work from him. Evans assured Caldecott that he was looking for Caldecott’s fluid style, with illustrations that exhibited much more movement and freedom in their lines. Though Evans worked with other illustrators, he did not know anyone else who could draw with such lively scenes that were transformed by the strategic placement of a few lines.

Over the years, Caldecott continued to travel frequently around Great Britain and to mainland Europe. In 1879, he met Marian Brind, to whom he became engaged, and married the following year in 1880. By 1884, sales of Caldecott’s Nursery Rhymes had reached 867,000 copies and he was considered internationally famous. Caldecott and his wife planned a trip to the United States soon after, sailing from England to New York City and then traveling down the East Coast. Once the couple reached St. Augustine, Florida, Caldecott had become gravely ill, most likely instigated by an unusually cold February in Florida. On February 12, 1886, Randolph Caldecott died from his illness, nearly forty years old. Though he was buried in a cemetery in St. Augustine, friends of Caldecott commemorated a memorial to him soon after his death and had it placed in the crypt in St. Paul’s Cathedral, London.

This artist's biography was written by Corryn Kosik, Rockwell Center Fellow, May 2018.

Illustrations by Randolph Caldecott

Additional Resources

Bibliography

Dalby, Richard. The Golden Age of Children’s Book Illustration. London: Michael O’Mara, 1991.

Davis, Mary Gould. Randolph Caldecott: An Appreciation. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1946.

Doyle, Susan, Jaleen Grove, and Whitney Sherman. History of Illustration. New York: Bloomsbury, 2018.

Engen, Rodney K. Randolph Caldecott: “Lord of the Nursery.” London: Bloomsbury, 1976.

Meyer, Susan E. A Treasury of the Great Children’s Book Illustrators. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987.