Josef Frank (1885-1967) was an Austrian-born Swedish architect and a designer of remarkable integrity. He worked under considerable artistic and political pressures to adhere to the norms of his peers and the design movements they embraced. Despite Frank’s lifelong status as an outsider, as a humanist amongst functional modernists, as a Jew in pre-war Vienna, and as an Austrian in Sweden, he developed a unified design approach and aesthetic that would leave a lasting legacy in Swedish design. His defined principles of “Accidentism” are present in all of his works but are perhaps manifested in their truest form of expression in his textile pattern designs.

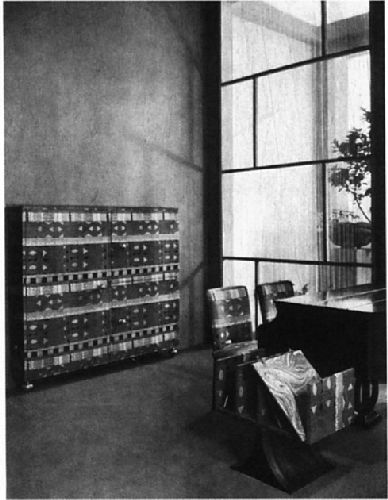

Frank, together with Oskar Wlach (1881-1963) and Walter Sobotka (1888-1972), founded the design and home furnishings firm, Haus & Garten, in Vienna in 1925. In her essay, titled “Light and Flexible—The Austrian Architect Josef Frank and the Vienna Furnishing Firm ‘Haus & Garten,’” Marlene Ott summarizes the firm’s overall approach to design by stating that Haus & Garten, “argued for the use of light, flexible and convenient, stand-alone pieces of furniture, combining different forms and materials, and for allowing homeowners to arrange them according to their own precise needs.”[1] This group of designers and their movement in furnishing came to be known as Neues Wiener Wohnen (New Viennese Living). The opposing creative approach to interior design at the time was the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, a design ideal that aimed for perfectly composed houses and interiors where every textile design, rug, piece of furniture, piece of art, or object was to be designed as a piece of a whole work of art.[2] The members of the Wiener Werkstätte, which was an Austrian designer and craftsman cooperative led by Austrian architect Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956), were proponents of this approach. Hoffmann exhibited a design for a music room as part of the 1929/1930 exhibition Wiener Raumkunstler at the Austrian Museum of Industry, in which Ott remarks that, “every piece of furniture was covered with the same fabric so as to create visual unity. By contrast, the Haus & Garten room designed by Josef Frank was furnished with individual, quite distinct, adaptable pieces.”[3] (fig. 1 and fig. 2) It was this flexible design philosophy that allowed Frank’s clients to feel like their homes were designed with them in mind, instead of feeling like they lived inside of an exhibition showroom or a museum display.

Fig. 1. Music room designed by Josef Hoffmann (executed by Anton Posposchil with furniture by Wiener Werkstätte), shown in the exhibition Wiener Raumkunstler at the Austrian Museum of Art and Industry, Vienna 1929-1930. Moderne Bauformen (Stuttgart: Julius Hoffmann Verlag, 1930).

Fig. 2. Living room designed by Haus & Garten (Josef Frank and Oskar Wlach), shown in the exhibition Wiener Raumkunstler at the Austrian Museum of Art and Industry, Vienna, 1929-1930. Moderne Bauformen (Stuttgart: Julius Hoffmann Verlag, 1930).

Haus & Garten’s main clientele in Vienna were upper-middle-class Jewish families that resulted from connections to Frank and Wlach’s architecture education at the Technische Hochschule in Vienna under Karl (Carl) Konig (1841-1915). Ursula Prokop writes in her essay “Josef Frank and ‘The Small Circle around Oskar Strnad and Viktor Lurje,’” that Konig, “was the first and only Jewish professor of architecture in Vienna at the time—a true novelty,” even though he was required to renounce his Jewish faith in order to receive the professorship.[4] Elana Shapira, in her essay titled “Sense and Sensibility—The Architect Josef Frank and his Jewish Clients,” suggests that Frank, “developed a unique principle of empowerment in design during his early career while designing the homes of members of the Viennese Jewish families.”[5] Shapira believes that Frank, by means of his “creative strategies,” was able to help these families “overcome their position as traditional ‘outsiders’ in Austrian society.”

In addition to his work in furnishings and interiors for Haus & Garten, as an architect “in the 1920s, Frank was active in the early years of Modernism, through the so-called Neue Bauen Movement.”[6] He was invited to be part of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM; International Congresses of Modern Architecture), an organization founded in 1928 by the Swiss architect Le Corbusier (1887-1965) that focused on spreading the principles of the Modern Movement. Even though Frank was invited to be part of the CIAM, he was still an outsider amongst modernists and left the group after its second meeting due to his “increasingly critical attitude” towards CIAM’s goal of developing Modernism into a new strict universal style.[7] CIAM’s tendencies towards austere functionalism through the construction of furniture using mainly industrialized materials like tubular steel, to Frank, resulted in an inhumane aesthetic which he abhorred.[8] Frank favored natural materials above all, firmly rejecting the tubular steel used by the Functionalists as part of the Deutscher Werkbund (German Association of Craftsmen) in their furniture designs. Consequently, for his Haus & Garten furniture, Frank placed the greatest value in the use of high-quality natural materials and good craftsmanship. Neither the Gesamtkunstwerk ideals of the Wiener Werkstätte nor the industrial machine-made products favored by the CIAM and the Deutscher Werkbund represented the correct approach to design to Frank.[9]

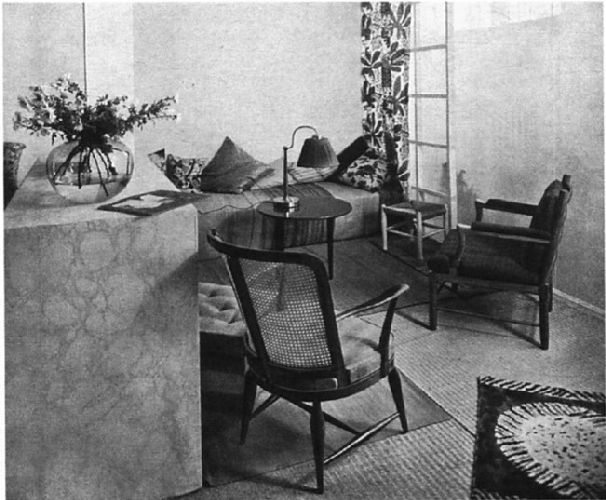

Frank’s entry in the Werkbund exhibition in Stuttgart in 1927 epitomizes his diametrically opposing design approach to that of his modernist peers who were also participating in the exhibition. Some of the most notable modernist architects of the era took part in the exhibition, including the German architects Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969) and Walter Gropius (1883-1969) who were two key figures in the founding and running of the Bauhaus. The Bauhaus was a German design school that taught the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk through the lens of industrialization and mass production. In their essay “Josef Frank: Spaces,” Mikael Bergquist and Olof Michelsen describe that, “instead of an interior decorated with modern tubular-steel furniture like the other exhibition buildings, Frank used padded seating from his company, Haus & Garten, brass lamps with sewn lampshades, and patterned curtains,” aiming to make the interior as comfortable as possible (fig. 3). Frank’s design was heavily criticized for his “feminine interiors,” and his duplex in the exhibition was called “Frank’s bordello” in the press.[10]

Fig. 3. Interior, duplex at the Weissenhof Estate, Stuttgart, 1927. Photo: Dr. Lossen & Co. Michael Bergquist and Olof Michelsen, “Josef Frank: Spaces,” Josef Frank—Against Design. Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Hermann Czech, Sebastian Hackenschmidt. (Vienna: MAK, 2015).

In addition to presenting an opposing perspective on modernist interior design at the Werkbund exhibition, Frank also struggled against the rising anti-Semitism and fascist paradigms of pre-war Vienna. Along with some of his Jewish colleagues, Frank participated in a major Viennese residential architecture project called the Werkbundsiedlung. In her essay, “Frank and ‘The Small Circle around Oskar Strnad and Viktor Lurje,’” Ursula Prokop points out that, “as a supporter of social democracy, he saw residential architecture as a means to improving social conditions…A humane architecture, free of pathos and monumentality, would become the model settlement that he initiated and planned between 1929 and 1932.”[11] Though the majority of the architects involved in the Werkbundsiedlung were leading Viennese architects, the project was met with anti-Semitic complaints by right-wing groups, highlighting the Jewish participants, [like Frank] and “claiming that too few ‘Austrians’” were involved.[12] Prokop claims that “these attacks, the economic failure of the project due to the economic crisis, and finally the split of the Werkbund accompanied by discord among its members… led to Frank’s emigration to Sweden. As a social democrat and a Jew, he saw no future for himself in Austria after the establishment of the Austro-fascist regime.”

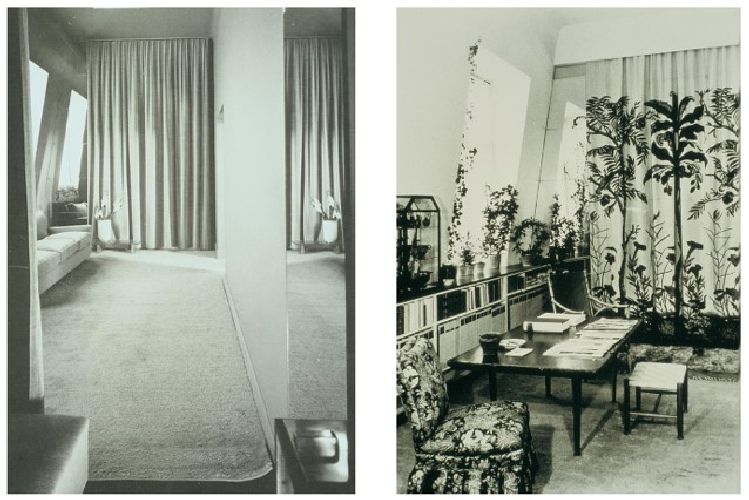

In 1933, he and his wife Anna, who was Swedish, settled in Stockholm thanks to Anna’s contacts. As soon as he arrived, he began working for Estrid Ericson (1894–1981), founder of the Stockholm-based design firm, Svenskt Tenn (fig. 4). At the time, Svenskt Tenn focused on manufacturing pewter pieces and furnishings for functional and utilitarian interiors, which was the leading design aesthetic in Sweden in the early 1930s. Coming from Austria, a cultural and design epicenter in Europe, arriving on the design scene in Sweden provided a shock, both for Frank and the Swedish design community. Frank regarded the Swedish aesthetic “bland and boring,” and the Swedish design community considered his style “gaudy.”

Fig. 4. Lennart Nilsson, Estrid Ericson and Josef Frank in the background, 1956. Svenskt Tenn Archives, Stockholm. Kristina Wangberg-Eriksson and Jan Christer Eriksson, “Josef Frank as Chief Designer at Svenskt Tenn in Stockholm, 1933-1967.” Josef Frank—Against Design. Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Hermann Czech, Sebastian Hackenschmidt. (Vienna: MAK, 2015).

At the time of Frank’s arrival to Sweden, the dominating design aesthetic was driven by the Svenska Slojdforeningen (The Swedish Society of Crafts and Design, or SSF). The SSF was an organization closely connected to the state in the 1930s. Its mandate from the government was to promote Swedish form and design on both the national and international levels. The exhibitions organized by the SSF were intended to set the standard for modern Swedish design.[13] It was after the Stockholm Exhibition in 1930, organized by the SSF, that Ericson branched out from pewterware to furnishings which eventually led to her collaboration with Frank that spanned more than three decades.[14] The Svenskt Tenn website claims that “Estrid Ericson turned over a new leaf in Swedish design when she offered Josef Frank a safe haven…Together the two transformed the sober and objective functionalism into something soft and homey.”[15] Ericson and Frank were thus able to disrupt the path of standardization that Swedish interior design was on in the late 1920s and early 1930s. This collaboration would result in Frank’s eventual acceptance as a Swedish designer and provided a platform for him to express his creative ideas through his designs for Svenskt Tenn.

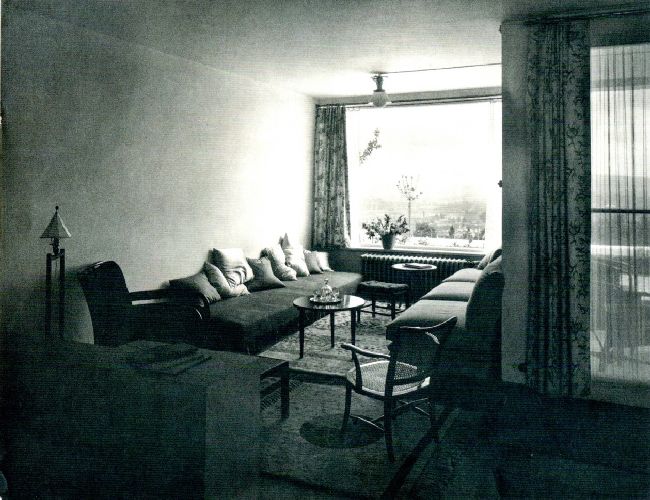

Despite Frank’s support from Ericson, his transition to the world of Swedish design was not without challenges. In 1934, only months after Frank arrived in Sweden, there was an exhibition of contemporary Swedish decorative art in Stockholm, and Frank designed a few living rooms to show for Svenskt Tenn. The media’s reception of Frank’s designs was not positive. Thommy Bindefeld, the current creative and marketing director at Svenskt Tenn, remarked in an interview that, “Frank presented sofas and chairs that were rounded, voluminous, and dressed in loud floral prints. These pieces went against what was the popular Swedish style at the time: understated and functional”[16] (fig. 5). Frank’s designs for the exhibition could be interpreted as a loud announcement of his arrival on the Stockholm design scene, as well as an almost unmistakable criticism of the “boring” standards set by the SSF in the early 1930s.[17] This exhibition, and its reception, echoes the Werkbund exhibition in 1927. It was Ericson’s vision and patronage and Frank’s ability to work under the umbrella of a well-established and already accepted brand that led to his success in Sweden. The true testament of this symbiotic creative relationship between Ericson and Frank, and her belief in the design aesthetic he wanted to promote in Sweden, is a picture of her apartment in 1930 before Frank arrived, and one in 1934, after Frank started working with her (fig. 6 and fig. 7). The shift from an extremely minimal and lifeless room with very light, neutral colors to an embrace of pattern and darker materials proves not just a professional vision when hiring Frank, but a personal belief in him and his ideas.

Fig. 5. Living room in model apartment #5 in Hall 35 of The Stockholm Exhibition of 1930, designed by Sven Wallander, Architect.

Fig. 6 and 7. Estrid Ericson’s apartment in 1930, before Frank’s arrival in Sweden (left). Estrid Ericson’s apartment in 1934, at the beginning of her collaboration with Frank (right). Svenskt Tenn Archives, Stockholm.

Frank’s refusal to align with any design movement or style of the time—rejecting Gesamtkunstwerk in Austria, then the functionalist modernism of the Deutscher Werkbund, and then the sober Swedish design aesthetic—made his work and his style difficult to categorize within the context of his time period. Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, the director of the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts/Contemporary Art in New York City, or MAK, described Frank as “the great humanist in modern architecture and design,” which aligns with Frank’s own extensive academic writing about his work.[18] In 1958, as part of an anniversary exhibition at Svenskt Tenn, Josef Frank: 25 Years in Sweden, Frank published an essay titled “Accidentism” in which he named and explained his design aesthetic and approach. The essay was considered so controversial by the broader Swedish design community that it was published alongside an editorial disclaimer distancing “Accidentism” and Frank from the views held by the SSF, which was the publisher of the journal.[19]

Frank explained that “Accidentism” aimed to “design our surroundings as if they were originated by chance.”[20] He rejected historical and universal styles that adhered to a strict set of rules in which “much is forbidden and little is allowed.” “Away with universal styles,” wrote Frank. “Away with the idea of equating art and industry, away with the whole system that has become popular under the name of functionalism. Modernism,” he said, “is what gives us complete freedom.” His socialist tendencies were reflected in his rejection of the “totalitarian symbols” he claimed to be in modern architecture and design, through their close association with industry and standardization. “Standardization that exceeds utility and becomes an aesthetic ideal is barbarism,” Frank wrote, asserting that this approach to standardized design is not conducive to the comfort of the people living within it. “Every place in which we feel comfortable — rooms, streets, and cities — has originated by chance.”[21] “Accidentism” can be used as a lens to look back on Frank’s work from his days designing Viennese interiors with Haus & Garten, the Deutscher Werkbund exhibit in 1927, his living room designs for the Stockholm exhibition in 1934; it is a word that seems almost necessary to describe his push against standardized design styles in favor of a comfort-based approach.

In addition to informing his approach to architecture and interior design, “Accidentism” can be seen embodied in Frank’s numerous textile and wallpaper pattern designs. While working for Ericson, Frank designed one hundred and sixty prints, many of which are still being used and sold today by Svenskt Tenn as part of their product inventory, or preserved in the Svenskt Tenn archives. Though Frank published many written works on his thoughts on architecture, room furnishings, and the power of fabrics therein, he wrote very little about the textile patterns themselves. His only statement on the subject can be found in an essay entitled “Rum och inredning” (“Rooms and Furnishings”) published in 1934 in the Swedish design and architecture magazine Form, in which he writes: “The freer the pattern, the better.”[22] In this case, the “freeness” of the pattern refers to its mystery, the inability of the viewer to be able to establish where the repeat begins and ends. Complex and organic patterns slow down the viewers’ gaze and invites them to immerse themselves in the world within the pattern, much the way one would in a landscape or a garden. In “Accidentism,” Frank writes that “what we need is variety and not stereotyped monumentality.”[23] Frank’s reliance on variety to create a world a viewer may lose themselves in is evident throughout his pattern designs.

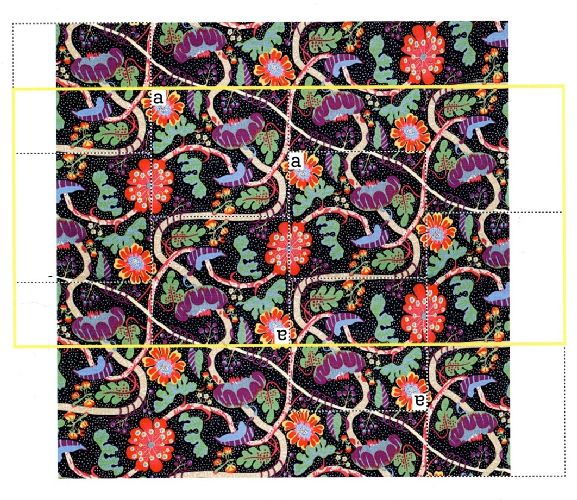

Frank’s production process mirrored the experience he sought to achieve for the viewer of his patterns. “The genius of Frank,” Bindefeld says, “was that he was designing and painting his repeat prints by hand. Some of his prints are really intricate and hard to understand, but he sat there at his kitchen table, which is where he always worked, designing and turning and twisting his paper as he painted.” Frank’s design process seemed to help him achieve “freeness” by becoming as immersed in a pattern’s complexity as he wished his audience to be. As an example, Bindefeld adds, “the repeat in the print Mirakel is not only shifted, but also turned upside down to get the lines moving in a way that doesn’t allow the viewer to see where it starts and where it ends.”[24] (fig. 8) By so deftly obscuring the joins of his patterns, Frank creates the illusion of added complexity, which helps to make his pattern seem more natural, more organic, and “as if originated by chance.” His use of patterns was a key ingredient in creating these cozy and inviting “accidentist” environments he strived to design for his clients.

Fig. 8. 180 degree rotation with drop repeat, Mirakel, House & Garten, ca.1925-1930. Claudia Cavallar and Sebastian Hackenschmidt, “The Freer the Pattern, the Better. Josef Frank’s Fabric Designs.” Josef Frank—Against Design. Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Hermann Czech, Sebastian Hackenschmidt. (Vienna: MAK, 2015).

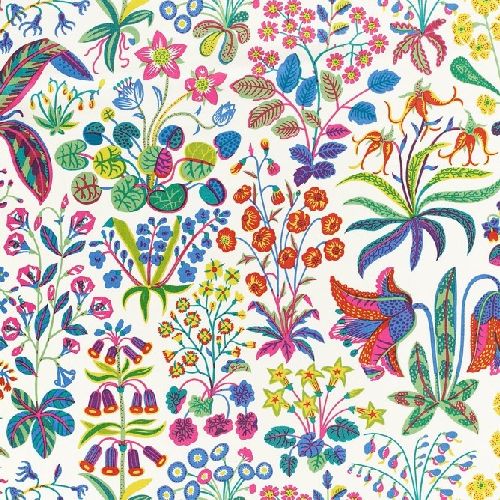

In his pattern, Under Ekvatorn (Under the Equator) (fig. 9), Frank creates a world of fantasy flowers and botanical illustrations that seem familiar; on closer inspection, it becomes clear that they are an amalgam of various species. Frank often drew inspiration from his vast collection of botanical field guides to create made-up plants and flowers. In his essay Rooms and Furnishings, he states that “every work of art is a puzzle…as it is the product of a process of thought that is for us unfamiliar and unfathomable. That is why we have a particular fondness for strange objects.”[25] This can certainly also apply to Frank’s pattern designs. The mystery behind how he designed them is part of what makes them so successful at being able to contribute to the comfort of the environment in which they are used. Claudia Cavallar and Sebastian Hackenschmidt, in their article “The Freer the Pattern, the Better” closely inspect the repeat patterns in Frank’s designs and explain that “unlike patterns in which individual motifs are simply repeated—which tend toward a certain uniformity and monotony—most of Frank’s textile designs seem dynamic, flowing, and complex.”[26] These are the qualities that make them “accidentist” patterns.

Fig. 9. Josef Frank, Under Ekvatorn (Under the Equator), 1941. Svenskt Tenn Archives, Stockholm.

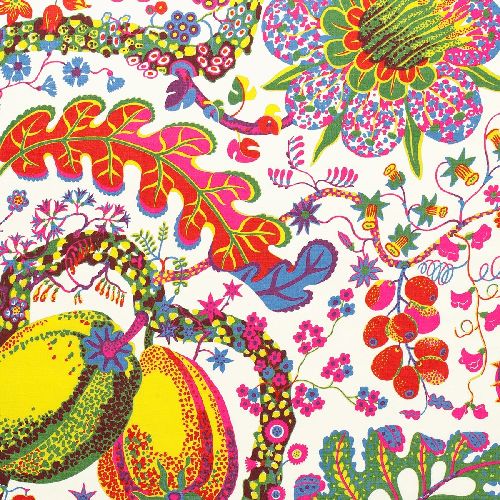

Sometimes it was his approach to the scale of a pattern, or its practical application, that provided that sense of mystery. The Brazil (fig. 10) print has one of the largest repeats among all of Frank’s textile patterns. He designed this print inspired by the rainforest with strong, vibrant colors and alien-like botanical motifs. By choosing to use this pattern as a sofa covering (fig. 11), the fragmentation, changes in direction, and overlaps necessary for furniture upholstery make it very difficult to discern the structure of the pattern and to determine its repeat.[27] Frank’s choice to use the pattern in this way leads to a sofa that looks almost like Frank took a brush and paint and painted directly on it, further providing a calming effect by sucking the viewer into it to try to discover every inch of it. This effect was what made the nature of the pattern “accidentist.”

Fig. 10. Josef Frank, Brazil, ca. 1943-45. Svenskt Tenn Archives, Stockholm.

Fig. 11. Josef Frank, Sofa, fabric covering Brazil. MAK—Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna.

Josef Frank spent a lot of time writing about his work and how it related to the design movements embraced by many of his contemporaries. Though his writings focused on his career as an architect and a designer of furniture and interiors, the same design philosophy he expresses in “Accidentism” can be used to analyze his textile pattern designs. Through the support and encouragement he received from the Jewish community in Vienna, and from Estrid Ericson in Sweden, he was able to freely express his “accidentist” design ideals and create the timeless textile patterns he designed for both Haus & Garten and Svenskt Tenn.

[1] Marlene Ott, “Light and Flexible—The Austrian Architect Josef Frank and the Vienna Furnishing Firm ‘Haus & Garten,’” Furniture History 46 (2010): pp. 217-234.

[2] Angela Volker, “Someone Sitting on a Persian Carpet Becomes Calm—Carpets in the interiors of Josef Frank,” Josef Frank—Against Design. Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Hermann Czech, Sebastian Hackenschmidt. (Vienna: MAK, 2015).

[3] Ott, “Light and Flexible,” p. 217.

[4] Ursula Prokop, “Frank and ‘The Small Circle around Oskar Strnad and Viktor Lurje,’” Josef Frank—Against Design. Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Hermann Czech, Sebastian Hackenschmidt. (Vienna: MAK, 2015).

[5] Elana Shapira, “Sense and Sensibility—The Architect Josef Frank and his Jewish Clients,” Josef Frank—Against Design. Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Hermann Czech, Sebastian Hackenschmidt. (Vienna: MAK, 2015).

[6] Ott, “Light and Flexible,” pp. 217-234.

[7] Michael Bergquist and Olof Michelsen, “Josef Frank: Spaces,” Josef Frank—Against Design. Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Hermann Czech, Sebastian Hackenschmidt. (Vienna: MAK, 2015).

[8] Ott, “Light and Flexible,” pp. 217-234.

[9] Herman Czech and Sebastian Hackenschmidt, Josef Frank—Against Design. (Vienna: MAK, 2015).

[10] Bergquist and Michelsen, Josef Frank—Against Design.

[11] Prokop, Josef Frank—Against Design.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Jan Norman, “Swedish Furniture Design from 1930 to 1960 and Josef Frank.” Josef Frank—Against Design. Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Hermann Czech, Sebastian Hackenschmidt. (Vienna: MAK, 2015).

[14] Kristina Wangberg-Eriksson and Jan Christer Eriksson, “Josef Frank as Chief Designer at Svenskt Tenn in Stockholm, 1933-1967.” Josef Frank—Against Design. Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Hermann Czech, Sebastian Hackenschmidt. (Vienna: MAK, 2015).

[15] Svenskt Tenn. “Since 1924.” Accessed December 2020. https://www.svenskttenn.se/en/about-svenskt-tenn/since-1924/

[16] Interview conducted by the author, Paloma Diaz-Dickson, on November 11, 2020.

[17] Norman, Josef Frank—Against Design.

[18] Alice Rawsthorn, “Josef Frank: Celebrating the Anti-Designer.” The New York Times, January 19, 2016. Accessed October 29, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/20/arts/design/josef-frank-celebrating-the-anti-design-designer.html 4/4

[19] Wangberg-Eriksson and Eriksson, Josef Frank—Against Design.

[20] Josef Frank, “Accidentism.” Form 54. 1958 (Stockholm: 1958) pp. 160-165.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Claudia Cavallar and Sebastian Hackenschmidt, “The Freer the Pattern, the Better. Josef Frank’s Fabric Designs.” Josef Frank—Against Design. Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Hermann Czech, Sebastian Hackenschmidt. (Vienna: MAK, 2015).

[23] Frank, “Accidentism,” pp. 160-165.

[24] Interview conducted by the author, Paloma Diaz-Dickson, on November 11, 2020.

[25] Josef Frank, “Rum och inredning.” Form. (Stockholm: 1934).

[26] Cavallar and Hackenschmidt, Josef Frank—Against Design.

[27] Ibid.