In art school we said, “One day we’ll be as good as Pyle or Abbey or J.C. Leyendecker.”

—Norman Rockwell

Many artists who have achieved significant recognition for their work were initially moved to create because they possessed a natural gift, and Norman Rockwell was no exception. Known as a masterful visual storyteller and the unrivaled creator of fictional realities that many 20th century Americans aspired to, Rockwell began his life as an artist in the world of his imagination, carefully honing his skills at home, at the dining room table in his family’s modest New York City apartment.

As a boy, the fledgling artist and his father, Jarvis Waring Rockwell, relished time spent reading and drawing in the evenings, finding inspiration for their sketches in the popular magazines of the day. Rockwell was surely acquainted with Howard Pyle’s stirring narratives for the pages of Harper’s Monthly and Scribner’s, and it is perhaps not surprising that daring pirates, fleets of battleships from the 1898 Spanish-American War, Native Americans, and frontiersmen were favored themes in his early repertoire. The young Rockwell also meticulously illustrated the richly described characters in the stories of Charles Dickens, as his father read aloud in his “even, colorless voice, the book laid flat before him to catch the full light of the lamp, the muffled noises of the city—the rumble of a cart, a shout—becoming the sounds of the London streets, our quiet parlor Fagin’s hovel or Bill Sikes’s room with the body of Nancy bloody on the floor.”[1] Rockwell recalled his visceral reactions to Dickens’s graphic depictions, but the complex tapestry of emotions and details thrilled him and prompted him from that time forward to look more deeply into our visual, sensory world. For Rockwell, stories were “the first thing and the last thing,” and would remain so throughout his seven-decade career.[2]

When Rockwell began the formal study of art after his sophomore year in high school, he was determined to forge a path in illustration—a career opportunity made possible by the illustrators of the Golden Age. Edwin Austin Abbey, Howard Chandler Christy, Charles Dana Gibson, Pyle, Frederic Remington, and others set the stage for later generations of artists, establishing that imagery created for mass distribution could be well conceived, aesthetically pleasing, and lucrative.

In America, publishing’s most rapid period of expansion occurred between 1865 and 1920, when the industry was established as a great national enterprise. A career in illustration was first seen as a viable profession during the Civil War, spurred by the public’s strong desire to witness historic events as they unfolded. To satisfy public demand and to attract readership and advertisers, magazines and newspapers hired artists like Theodore Russell Davis and Winslow Homer as reporters, dispatching them to capture impressions of life on and around the battlefield. After the Civil War, hundreds of new periodicals were launched. While only seven hundred periodicals existed in 1865, by 1900 nearly five thousand more had come into being.[3] Publications like The Century Magazine and Harper’s Monthly reserved a full fifteen percent of their pages for illustrations at that time, offering ample opportunities for artists. By the 1890s, advances in pictorial technology had made it possible for an artist’s work to be seen as it was created, without the need for interpretation by a skilled engraver’s hand. Abbey, Homer, Pyle, and others had established illustration as a significant art form in which high standards and broad appeal were not yet in contradiction.[4]

At the end of the nineteenth century and during the early decades of the twentieth, books and periodicals were a lifeline to the larger world. When Rockwell’s first cover for The Saturday Evening Post appeared in 1916, the Post, Good Housekeeping, Ladies’ Home Journal, McCall’s, Woman’s Home Companion, and other leading journals had vast, loyal followings and were richly illustrated, enticing readers to purchase magazines and the products featured within them. By 1930 the weekly Saturday Evening Post boasted a circulation of nearly three million, but the anxiously awaited magazines were shared among family and friends, bringing readership even higher.[5] Far more than just picture makers, illustrators became influential visual commentators whose art was linked to an industry determined to provide a “clear and friendly roadmap to the American dream.”[6]

Rockwell and his fellow students at the Art Students League in New York felt the weight of history on their shoulders. “To us,” Rockwell commented, illustration was “an ennobling profession . . . That’s part of the reason I went into illustration. It was a profession with a great tradition, a profession I could be proud of.”[7] He began his studies at the League in 1911, when publishing was in its heyday, and legends of Pyle’s time there as a drawing and composition student from 1876 to 1878 were still actively shared among the school’s accomplished faculty.[8] Even the League’s longtime models, who were said to have posed for Pyle, were questioned by art students: “How did he begin a painting?” “What kind of paints did he use?” “Did he make preliminary sketches?” Pyle’s artistic association with historical subjects and “fine writing” rather than advertising was valued, as advertising was considered far too commercial by an idealistic Rockwell and his fellow students. “Had Pyle or Abbey done advertisements? we asked each other. No. And we wouldn’t either.”[9] Rockwell’s prediction did not ultimately stand, as at least one quarter of his body of four thousand works was created for our nation’s most prominent corporations. [10]

At the League, Rockwell’s mentors and teachers, the illustrator Thomas Fogarty and the painter and anatomist George B. Bridgman, held Pyle up as a revered model for their students. Fogarty was pragmatic in his approach to teaching and inspired his students to emulate successful practitioners in class. After summarizing a story, he queried his aspiring illustrators on how to best represent it in pictorial form. Reproductions revealing the approach that Pyle and other well-known artists had taken to the same text were discussed, and their conceptual and compositional decision-making process was explored.[11] These lessons proved effective for Rockwell, who, with Fogarty’s recommendation, received his earliest professional commission, to create illustrations for C. H. Claudy’s “Tell Me Why” Stories in 1912.[12]

Bridgman, whose tenure at the League lasted for almost half a century, paid homage to Pyle by sharing reflections on the artist and his legacy with Rockwell and others who remained after class to absorb his wisdom.[13] For Rockwell, Pyle was the embodiment of illustration’s Golden Age. He remembered clearly both Bridgman’s emotional pronouncement that the great artist had died—on November 9, 1911, at just fifty-eight years of age—and his difficulty in conducting drawing class through tears that day.[14]

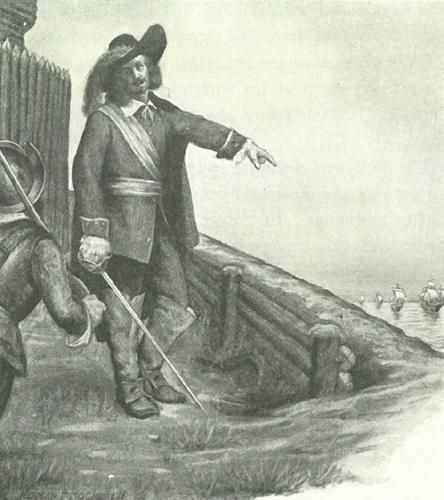

Fig. 1. Howard Pyle, An English Fleet Came Sailing Up the St. Lawrence, 1911

Pyle’s insistence on authenticity made a significant impact on Rockwell, who remembered him as “a historian with a brush. His drawings of colonial days, of the Revolution, of pirates, were authentic re-creations, backed by years of study and research.”[15] Rockwell discussed his artistic influences in a 1960 interview published in Design magazine, naming Rembrandt as most significant to his artistic development and expressing admiration for Pieter Bruegel, J.A.D. Ingres, Pablo Picasso, and Jan Vermeer. Pyle and J.C. Leyendecker were identified as having had great impact during his impressionable student days.[16] In An English Fleet Came Sailing Up the St. Lawrence (Fig. 1), a drawing featuring the French navigator and explorer Samuel de Champlain, Rockwell emulated the compositional structure and attention to the details of character, costume, and setting in Pyle’s Arrival of Stuyvesant in New Amsterdam (Fig. 2), an illustration published a decade earlier in Harper’s Monthly.

Fig. 2. Howard Pyle, Arrival of Stuyvesant in New Amsterdam, 1901

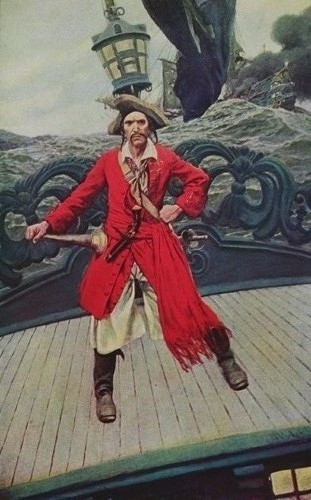

Throughout his career Rockwell kept Pyle’s imagery close at hand in books and prints, which were an ongoing source of inspiration. Pyle’s Captain Keitt (Fig. 3) adorned the walls of Rockwell’s Prospect Street studio in New Rochelle, New York, and he relished seeing it again after his 1918 discharge from service in the United States Navy during World War I.

Fig. 3. Howard Pyle, Captain Keitt, 1909

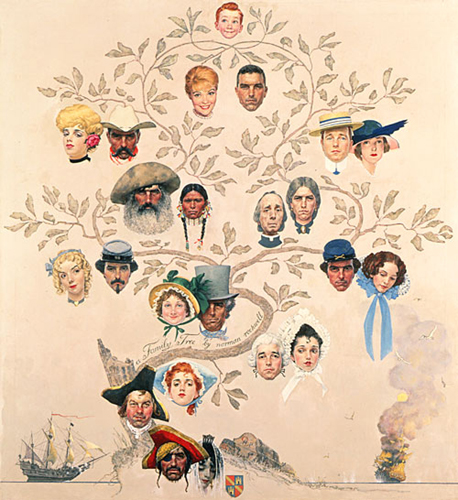

“Look at that fiery crimson coat against the dull green sea,” he remembered thinking, intending to create that effect in his own work someday.[17] Years later Rockwell paid homage to Pyle in Family Tree (Fig. 4), a cover painting for The Saturday Evening Post, which traces the ancestry of a fictional American family.

Fig. 4. Norman Rockwell, Family Tree, 1959

In the piece the family’s lineage is rooted in the union of a weathered pirate and a demure Spanish princess swept away from a sinking galleon—a vessel clearly inspired by Pyle’s theatrical sailing ships, such as the one pictured in An Attack on a Galleon (Fig. 5). The initials H. P. are inscribed on the chest in Rockwell’s image, echoing the inscription on William Kidd’s coffer in Pyle’s painting Buried Treasure (Fig. 6), an illustration reproduced first in Harper’s Monthly and later in Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates (1921), which Rockwell owned.

Fig. 5. Howard Pyle, An Attack on a Galleon, 1905

Rockwell readily acknowledged that great art is not created in a vacuum, and his extensive library of prints and books was reflective of that sentiment. Even after a 1943 fire devastated Rockwell’s Arlington, Vermont, studio, including “all my antiques, my favorite covers and illustrations which I’d kept over the years, my costumes, my collections of old guns, animal skulls, Howard Pyle prints, my paints, brushes, easel, my file of clippings—everything,” he made sure to bring Pyle’s imagery back into view.[18]

.jpg)

Fig. 6. Howard Pyle, Buried Treasure, 1902

Though not a collector in the traditional sense, Rockwell enjoyed surrounding himself with original works by artists he admired. Modest pieces by major talents like Leyendecker, Maxfield Parrish, Edward Penfield, Pyle, and Arthur Rackham, among others, filled the walls of his home and studio, a reminder of qualities to which he continually aspired. Thomas Rockwell, the artist’s son, recalled that several works by Pyle were brought to his father’s attention by E. Walter Latendorf, one of the first art dealers in New York to handle illustration art.[19] Beautifully illuminated letters from The Wonder Clock (1887), Pyle’s original book of fairy tales, as well as elegant linear drawings for Twilight Land (1894) and The Evolution of New York (1893) were in Rockwell’s personal collection.[20]

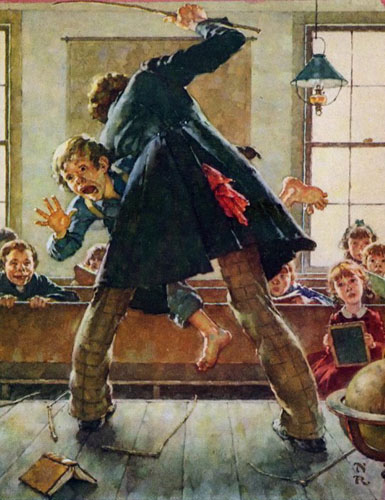

Fig. 7. Howard Pyle, I Will Teach Thee to Answer Thy Elders, 1896

Another treasure, I Will Teach Thee to Answer Thy Elders (Fig. 7)—Pyle’s full-color accompaniment to S. Weir Mitchell’s “Hugh Wynne, Free Quaker” in The Century Magazine—clearly captured Rockwell’s imagination. The piece is visually linked to another classroom altercation, a flogging portrayed in a Rockwell illustration for Mark Twain’s (Samuel L. Clemens’s) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Norman Rockwell, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, 1936

“It’s hard to say what one artist gets from studying the works of other artists,” Rockwell reflected. “I guess an artist just stores up in his mind what he learns from looking at the work of other artists. And after awhile all the different things he has learned become mixed with each other and with his own ideas and abilities to form his technique, his way of painting.”[21] Pyle’s insistence on authenticity and his ability to render dynamic, meticulously designed compositions that speak of humanity inspired Rockwell to demand the same level of excellence from himself, in his own way. When asked what art he would take to a desert island, in a 1962 interview for Esquire magazine, Rockwell replied without hesitation, a “Rembrandt or two” and “a good Howard Pyle.”[22]

The epigraph is from Norman Rockwell (as told to Tom Rockwell), Norman Rockwell, My Adventures as an Illustrator (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1988), 166.

[1] Norman Rockwell (as told to Tom Rockwell), Norman Rockwell, My Adventures as an Illustrator (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1988), 28–29.

[2] Norman Rockwell, Recorded Talk at the Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles, 1949, Norman Rockwell Museum Audio Recording Collection, 1949–2002, Norman Rockwell Museum Archival Collections, Stockbridge, Mass.

[3] On the expansion of the publishing industry, see Susan E. Meyer, America’s Great Illustrators (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1978), 8–24; and Meyer, Great American Illustrators (New York: Galahad Books, 1989).

[4] Laura Claridge, Norman Rockwell: A Life (New York: Random House, 2001), 87.

[5] On circulation of The Saturday Evening Post, see Jan Cohn, Creating America: George Horace Lorimer and The Saturday Evening Post (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1989), 165, 307, n. 18.

[6] Alice A. Carter, Ephemeral Beauty: Al Parker and the American Women’s Magazine, 1940–1960 (Stockbridge, MA: Norman Rockwell Museum, 2007), 12.

[7] Rockwell, Norman Rockwell, 52–53.

[8] Delaware Art Museum, Howard Pyle: The Artist, the Legacy (Wilmington, DE: Delaware Art Museum, 1987), 7–8.

[9] Rockwell, Norman Rockwell, 52.

[10] For a complete listing of works by Norman Rockwell, see Laurie Norton Moffatt, Norman Rockwell: A Definitive Catalogue (Stockbridge, MA: Norman Rockwell Museum, 1986). Rockwell’s illustrations for advertising campaigns are in the first volume.

[11] Ibid., 64–65.

[12] C. H. Claudy, “Tell Me Why” Stories (New York: McBride, Nast and Company, 1912). Rockwell produced eight illustrations for the interior of this book. Rockwell mentions that Thomas Fogarty recommended him for this job in Norman Rockwell, 70.

[13] Rockwell, Norman Rockwell, 61.

[14] Ibid., 97.

[15] Ibid., 52.

[16] Mary Anne Guitar, “A Closeup Visit with Norman Rockwell,” Design (Sept.–Oct. 1960).

[17] Rockwell, Norman Rockwell, 134.

[18] Ibid., 324.

[19] Thomas Rockwell, Off His Walls: Selections from the Personal Art Collection of Norman Rockwell (Stockbridge, MA: Norman Rockwell Museum, 1991), unpaginated.

[20] First published in serial form in Harper’s Young People between October 1889 and January 1891, Twilight Land is a collection of stories written and illustrated by Howard Pyle (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1894). “The Evolution of New York” is a detailed history of the settlement of New York by Thomas Janvier that was also illustrated by Pyle. The illustration in Rockwell’s collection details the Dutch West India Company’s departure from the settlement of Fort Amsterdam as the English took possession of it on September 8, 1664. It appears in Janvier, “The Evolution of New York: First Part,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 86, no. 66 (May 1893): 829.

[21] Rockwell, Norman Rockwell, 43.

[22] “An Artist’s Interview,” Esquire (January 1962): 76.

_385_385_c1_60_60_c1.jpg)