Following the abolition of American chattel slavery in the 1860s, many Whites feared the integration of Black peoples into their communities. A way to maintain dominance and exert control throughout the broader American community was to create fictitious narratives about previously enslaved Black Americans. In modern times, these acts have come to be defined as acts of White supremacy.

Anti-Black sentiments, beliefs, and practices were not confined to this period of time, though, as demonstrated by the innumerable protests and movements taking place all over the country in 2020. Here we see the demand to dismantle White supremacy and to abolish and/or reform the many anti-Black institutions and systems our country runs on. This growing awareness demonstrates that there are few places not touched, influenced, or still upholding racism.

Children’s books are “the books people read before they are fully formed. Their ideas about themselves and the world in which they live are still developing.”[1] Yet children’s books have also been utilized to perpetuate racist depictions and stereotypes (e.g., Helen Bannerman’s Little Black Sambo, 1899). Around the turn of the 20th century, illustration became a medium which was commonly utilized in magazines and books; however, illustration was also widely dispersed to create and disseminate demeaning, violent, and racist misinformation about marginalized peoples in the United States and abroad. In her contribution to A Companion to Illustration: Art and Theory (2019), Robyn Phillips-Pendleton explains, “Blatant, subtle, or perceived racial stereotypes, created by White illustrators and sanctioned by their editors, have been woven into the fabric of the relationship between imagery and text for centuries, and were instrumental in shaping race and cultural perception, mainly in the United States, from the pre-colonial era to the present.”[2] In addition to books for children, food packaging, advertisements, literature, and cartoons commonly featured fabricated depictions of Black Americans.

What message does it send to Black children, if the literature they read offers racist depictions, or no depictions of them at all?

In an examination of the article “The All-White World of Children’s Books,”[3] Dr. Gerald L. Early explains how, “most children’s books, in the matter of dealing with race, were not only detrimental to the hearts and minds of black children but to white children as well.”[4] The impact of false and racist depictions of Black Americans becomes evident when considering the following:

“The ability to create language, make meaning, and transform reality by the use of symbols provides children creative opportunities to engage the world. Language becomes the vehicle for children to locate their place in the world and to understand the social and political implications of their society... Providing children a space to locate themselves in history makes them present as agents in the struggle for self-definition and cultural identity. Their learning, then, becomes a pedagogy of empowerment and liberation.”[5]

To examine mid-century examples of children’s books like John Steptoe’s Stevie (1969) up to modern-day examples like Kwame Alexander and Kadir Nelson’s collaborative efforts for Undefeated (2019), it becomes clear that Black creatives have persistently found inventive ways to help Black children locate themselves in the world and in history. American artists and creatives like Tom Feelings, Maya Angelou, Betye Saar, Carolyn Mims Lawrence, Jacqueline Woodson, Spike Lee, Toni Morrison, bell hooks, and countless others have contributed to positive and richly diverse narratives and experiences of Blackness in the last six decades.

For the scope of this piece, I examine the work of illustrators Vashti Harrison, Jerry Pinkney, and Faith Ringgold. These three American artists utilize children’s books to revise, reimagine, and retell narratives of Black Americans, while constructing positive imagery for young readers, who may still be learning to make meaning of the world while discovering their place in it. Harrison, Ringgold, and Pinkney each work masterfully in their chosen medium, which ranges from quilting, watercolor, and digital illustration. And similarly, the stories they illustrate drift between the historical and the imagined.

Faith Ringgold: Quilting as Story-Telling

Faith Ringgold (b.1930) is the author and illustrator of several children’s books, and is most widely regarded for her quilt-work. Ringgold was born and raised in Harlem, New York, and her career as an artist spans more than forty years. She has won numerous awards and honors, including several for her first published children’s book, Tar Beach (1991).

Quilting, for many Black Americans, has ties to their ancestral lineage. Ringgold’s use of quilts in children’s books provides a reference point in time and space for Black children to locate themselves and their predecessors. In the “The Rhetoric of Quilts: Creating Identity in African-American Children's Literature,” Olga Idriss Davis states, “The quilt uncovers the choice of symbols Black women used within their community to create a shared, common meaning of self and the world. Thus, the quilt serves as a vehicle for reinventing the symbolic expression of identity and freedom.”[6]

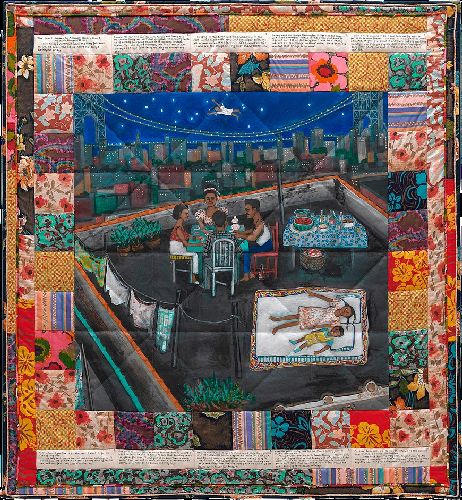

Fig. 1. Faith Ringgold, Woman on a Bridge of Tar Beach #1 of 5, 1988. Acrylic, canvas, printed fabric, ink, and thread. 74 1/2 x 68 1/2 in. (189.5 x 174 cm.) Collection of the Guggenheim Museum, New York.

In Tar Beach, Ringgold illustrates the story of Cassie Louise Lightfoot through the mediums of quilting and painting. The result is one of her most memorable pieces, Woman on a Bridge #1 of 5: Tar Beach (fig. 1). In this text, she confronts issues of racial discrimination and the stigmatization of mixed heritage folks in American culture. In this case, Cassie’s father is denied membership to a union because of his Black and Indigenous lineage. Cassie, however, attempts to overcome this particular obstacle by flying over the union building where her father is employed to stake her claim to it, so that her family may reap the rewards of ownership.

Tar Beach also centralizes themes of autonomy and self-ownership, as Cassie exclaims that because she can fly, she is free to go wherever she wants, for the rest of her life.[7] This concept is radical for a young Black child (and especially for a young Black girl) living in America.

In 1992, Ringgold published a sequel to Tar Beach, titled, Aunt Harriet’s Underground Railroad in the Sky. In Aunt Harriet’s, we are again visited by Cassie and her brother BeBe. The two siblings are separated and eventually reunited through the help and guidance of Harriet Tubman. Though Aunt Harriet’s is a work of fiction, Tubman is one of the most known and celebrated figures in the abolition of American slavery who led hundreds of enslaved African-Americans to freedom. Davis summarizes the impact of this narrative stating, “The role of Aunt Harriet provides young readers an understanding of the quilt as a code of solidarity, shelter, and safety for slaves in the ante-bellum period. Not only does Ringgold's story locate young readers in history, but it also challenges them to learn of the quilt as a guiding force when danger is near.”[8]

Through Ringgold’s body of work, we see her expert ability to weave not just quilts, but also history, imaginative invention, truth-telling, freedom, and joy for Black children (and all children). The effect is accessibility to past, present, and future.

Jerry Pinkney: Recapturing and Boldly Revising Old Narratives

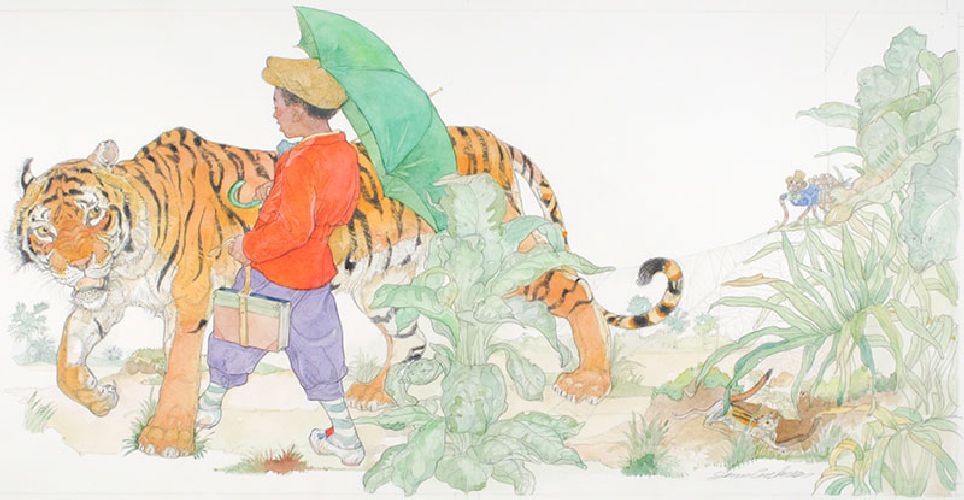

Fig. 2. Jerry Pinkney, The Tiger Stopped and Looked at Sam, 1996. Illustration for Sam and the Tigers: A Retelling of Little Black Sambo by Julius Lester. Watercolor on paper. Collection of the artist.

Jerry Pinkney’s (b.1939) career as an illustrator spans six decades. He is lauded for his masterful use of watercolor and other paint media in illustrating narratives for children’s books. Pinkney is the recipient of a number of awards and honors, including several Randolph Caldecott Medals and Coretta Scott King Book Awards, both of which are awarded to authors and illustrators of distinguished children’s books.

In the essay “Call and Response,” Pinkney explains that as his family had migrated from the American South, he became “acquainted with the oral tradition of storytelling” and recalls being told The Tales of Uncle Remus and John Henry as a child.[9] Originally born and raised in Philadelphia, PA, Pinkney grew up reading Little Black Sambo, which was “both appealing and affirming for him,” as the story follows a young Black boy, who outsmarts several tigers threatening to eat him.[10] In collaboration with author Julius Lester, the two revisited, revised, and retold the tales of Uncle Remus, John Henry, and Little Black Sambo—which became Sam and the Tigers (1992).

Little Black Sambo features Sambo drawn as a “pickaninny,” which is a derogatory style of caricature used (primarily during the mid-19th and early 20th century) to portray Black children as unkempt and uncivilized. Helen Bannerman’s Sambo inspired numerous remakes; most relied upon the same racist imagery and storyline. However, Lester and Pinkney’s revision features Sam (fig. 2), replacing Sambo, who lives in Sam-sam-sa-mara, a place where everyone is also named Sam. Through Pinkney's use of watercolor and Lester’s story-telling, Sam is transformed into a more admirable image of a Black child with an extravagant sense of style, and the two manage to maintain the cleverness of Bannerman’s original character.

John Henry has a less controversial history than Sambo, and Henry is a heroic figure in American folklore. Lester and Pinkney assembled parts from several sources to construct this narrative, tinged with magic-realism, of a newborn who stretches into adulthood in an instant before his parents’ eyes.[11] Pinkney renders John Henry and his surroundings in various hues of brown and grey with few moments of color—mostly reds and yellows. However, there are several moments where Henry is wrapped in a rainbow: first, when Henry is born and thrust into the world; again, when he breaks an impossibly large boulder; and finally, when his heart explodes after plowing through a mountain.

Pinkney and Lester’s handling of these tales and their respective characters demonstrate a deep reverence for them, and they instill them with dignity and undeniable beauty. Dr. Gerald L. Early explains, “Jerry Pinkney, as a children’s book illustrator, is also part of a tradition or at least part of an aspiration toward a tradition, of African-Americans creating an anti-racist children’s literature.” Early goes on to explain how the reworkings of these three narratives function “to right the wrongs of the original.”[12]

Though the original tales of Uncle Remus and Sambo represent racist tropes created to demean Black Americans, Lester and Pinkney’s revisions assist young Black children, and all children, in locating themselves in history and society.

Vashti Harrison: Giving Voice to New Narratives

To clarify, the term “new narrative” does not suggest that the following topics are new concerns for Black Americans. Instead, it implies that these topics have not been commonly discussed in the medium of children’s books—or in dominant discourse.

Vashti Harrison (b.1988) is both a writer and illustrator of children’s books which contain complex conversations about Blackness. As a fairly new voice in the world of children’s books, both her solo and collaborative efforts have garnered much attention in the last year. It is through her illustrative work on Lupita Nyong’o’s Sulwe (2019) and Matthew A. Cherry’s Hair Love (2019) that she brings issues of internalized racism and White supremacy to the forefront. Subsequently, this provides children an opportunity to become “agents in the struggle for self-definition and cultural identity.”[13]

Colorism is defined by Oxford Languages as, “prejudice or discrimination against individuals with a dark skin tone, typically among people of the same ethnic or racial group.”[14] A notable and key function of colorism is that it favors and affords those in closer proximity to Whiteness (e.g., lighter skin tones) with more privileges than those with darker skin tones. Proximity to Whiteness and passability (e.g., one being able to pass as White) are forms of social currency that benefit those with lighter skin, straighter hair, and other physical features not usually associated with Black peoples of the world.

In Sulwe (fig. 3), written by actor Lupita Nyong’o, Harrison illustrates the struggles faced by those with darker skin. Sulwe is mistreated by her peers because her skin is darker than most, while her sister, the lightest member of her family, is well-received and favored by the same children. Sulwe attempts to escape this mistreatment by becoming more beautiful, which she has come to associate with having lighter skin.

Fig. 3. Vashti Harrison. Digital Illustrations for Sulwe by Lupita Nyong’o. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2019.

By the text’s end, Sulwe becomes a tale of a young girl—born the color of midnight—who grows to recognize and appreciate the beauty of her skin tone. Historically, though, many dark-skinned children, specifically, young Black girls, have not had opportunities to see their struggles with colorism reflected in the literature created for them. Nyong’o and Harrison’s efforts in Sulwe aim to address this.

Cherry and Harrison’s collaboration for Hair Love exemplifies the idea that there can be pride, joy, and beauty in Black hair, which challenges the historical politicization and policing of Black hair by individuals and institutions. Phillips-Pendleton explains, “Stereotypes affected how Black women saw themselves, and hair and the treatment of the head with hats or scarves signified a variety of social codes and meaning.”[15] The mammy trope was fabricated and used to demarcate Black women as unattractive. The mammy trope, utilized in a similar manner as Sambo, was often portrayed in clothing that covered her from head-to-toe. These representations have historically had a negative impact on the self-esteem and self-concepts of Black girls and women alike.

Zuri, the main character of Hair Love, is portrayed flaunting her long locks of kinky and curly hair in a number of beautifully braided, twisted, and ponytailed styles—all done by her lovingly attentive father. In addition to challenging concepts of Black hair as beautiful, this text addresses the harmful stereotype of Black men as absentee and/or inattentive fathers, which has persisted for decades. The relationship between Zuri and her father, as illustrated by Harrison, contributes to positive imagery for young children reading this book.

Conclusion: Looking Ahead to Black Futures

As a way to counter racist depictions, American children’s books written and/or illustrated by Black artists, primarily focus on constructing and instilling a sense of pride in the collective Black American identity. Through examining the works of Harrison, Pinkney, and Ringgold, it becomes clear that this practice has continued over generations without fail. This communicates a continued need of Black Americans to highlight our history, rewrite false and harmful narratives, create representation and space for dialogue where previously there was little, and give voice to what has fallen on disinterested ears.

While a disproportionate number of Blacks, Indigenous, and other people of color remain oppressed, the types of conversations illustrated by Ringgold, Pinkney, Harrison, and others are necessary. New platforms for more complex conversations are emerging, and there is a shift occurring where Black creatives are going within to address continued racist beliefs. We continue the work to challenge, shift, and reimagine limiting narratives that we did not create. It is imperative that creatives of all backgrounds work to establish realistic portrayals and narratives in children’s books, which hold the unique ability to inspire little humans—and the adults who read them, too—to imagine a world where we are all free from oppressive systems and where Black Americans can look beyond the past, as well as locate ourselves in Black futures.

[1] Nel, Philip. “The Fall and Rise of Children’s Literature.” American Art, Spring 2008, 23.

[2] Phillips-Pendleton, Robyn. “Race, Perception, and Responsibility in Illustration.” In A Companion to Illustration: Art and Theory, edited by Alan Male, 571. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2019.

[3] Early, Gerald L. “Jerry Pinkney: American Illustrator.” In Witness: The Art of Jerry Pinkney, edited by Wren Bernstein, Stephanie H. Plunkett, and Joyce K. Schiller, 43-48. Stockbridge, MA: Norman Rockwell Museum, 2010.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Davis, Olga Idriss. “The Rhetoric of Quilts: Creating Identity in African-American Children's Literature.” African American Review, Spring 1998, 67-68.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ringgold, Faith. Tar Beach. New York: Crown Publishing Group, 1991.

[8] Davis, “The Rhetoric of Quilts,” 70.

[9] Pinkney, Jerry. “Call and Response.” In Witness: The Art of Jerry Pinkney, edited by Wren Bernstein, Stephanie H. Plunkett, and Joyce K. Schiller, 26. Stockbridge, MA: Norman Rockwell Museum, 2010.

[10] Plunkett, Stephanie Haboush. “Introduction: Witness: The Art of Jerry Pinkney.” In Witness: The Art of Jerry Pinkney, edited by Wren Bernstein, Stephanie H. Plunkett, and Joyce K. Schiller, 10. Stockbridge, MA: Norman Rockwell Museum, 2010.

[11] Lester, Julius. John Henry. New York: Dial Books, 1994.

[12] Early, “Jerry Pinkney: American Illustrator,” 45-48.

[13] Davis, “The Rhetoric of Quilts,” 67.

[14] The definition for colorism is provided by Oxford Languages.

[15] Phillips-Pendleton, “Race, Perception, and Responsibility in Illustration,” 584.