Fig. 1. René Gruau, Tribute to Christian Dior's first fashion collection in 1947, 1987

The majority of fashion illustrations were created to be seen on a page at close range, allowing for the personal experience associated with books and letters. Therefore, fashion illustrations possess a unique feeling of intimacy, with the image held in the viewer’s hand, as well as an urgency, the need to stop us in our tracks before we turn the page.

Fashion illustration requires the unique ability to use pen or brush in such a way that it not only captures nuance through gesture but is also able to transform the graphic representation of a garment, accessory, or cosmetic into an object of desire. The job of the fashion artist is to ‘tell the story of the dress.’

Fig. 2. Charles Dana Gibson, The Gibson Book, Volume II, 1907

THE BEGINNING OF FASHION ILLUSTRATION

Fashion illustration began in the sixteenth century when global exploration and discovery led to a fascination with the dress and costume of people in many nations around the world. Books illustrating the appropriate dress of different social classes and cultures were printed to help eliminate the fear of change and social unrest these discoveries created.

Between 1520 and 1610 more than two-hundred collections of such engravings, etchings, or woodcuts were published, containing plates of figures wearing clothes particular to their nationality or rank. These were the first dedicated illustrations of dress and the prototype for modern fashion illustration. The illustrations likely found their way to dressmakers, tailors, and their clients, serving to inspire new designs.

Fig. 3. Abraham Bosse, Un homme se dirigeant à droite monte un degré, 1629

Seventeenth-century artists Jacques Callot (1592-1635) and Abraham Bosse (1602-1676) both used modern engraving techniques to produce realistic details of the clothes and costumes of their times.

The journals, which began to be published in France and England from the 1670s onward, are considered the first fashion magazines, among them Le Mecure Gallant, The Lady's Magazine, La Gallerie des Modes, Le Cabinet des Modes, and Le Journal des Dames et des Modes. The increase in the number of periodicals and journals produced during this time was in response to an increasingly well-informed female readership eager for the latest news of fashion. Illustrations of current male styles became equally as important as those for women by the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Fig. 4. Jacques Callot, Etching from La Noblesse, ca.1620

THE FASHION PLATE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

The fashion plate came into its own in the late eighteenth century, flourishing in Paris with publications such as Horace Venet's Incroyables et Merveilleuses. This series of watercolor fashion drawings under Napoleon I was engraved by Georges-Jacques Gatine (1773-1824) as a series of fashion plates. France's position as the arbiter of fashion ensured that there was a constant demand, at home and abroad, for fashion illustration. This interest in, and growing access to, fashionable dress resulted in the introduction of more than one hundred and fifty fashion periodicals during the nineteenth century, all of which included fashion plates. These highly detailed fashion illustrations captured trend-driven information and provided general dressmaking instruction. These illustrations were created by such talented artists as the Colin sisters and Florensa de Closménil.

Fig. 5. Georges-Jacques Gatine, Le Goût du Jour, No. 21: Les Modernes Incroyables, from Caricatures Parisiennes, ca.1815

Couture fashion emerged in the 1860s. Fashion houses hired illustrators who would work directly with the couturier to sketch the new designs as the maestro draped the fabric onto a live model. They also drew illustrations of each design in the finished collection which could then be sent to clients. By the end of the nineteenth century, hand-colored prints were replaced by full-color printing. Fashion plates began to feature two figures, one of which is seen from the back or the side so that the costume could be seen from more angles, making it easier to copy. The focus of nineteenth-century illustrators was on accuracy and details. They conformed to static, iconographic conventions in order to provide information and instruction to their viewers.

Fig. 6. Florensa de Closménil, La Mode, 25 septembre 1846: Chapeaux de Mme Penet, 1846

Fashion illustration by the turn of the twentieth century became highly graphic and based more on the artist's individual style. For example, Charles Dana Gibson's (1867-1944) scratchy renderings of the modern American woman, with upswept hair and shirt-waist, defined a type as well as provided a humorous, sometimes satirical, commentary on contemporary American life.

FASHION MAGAZINES AND ILLUSTRATION IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

The early decades of the twentieth century saw the first flowering of fashion illustration in its modern sense. The business of drawing became a vocation as the circulation of the latest styles became an increasingly lucrative business. Fashion, formerly the work of individual artists, was becoming an industry, producing new merchandise in unprecedented quantities to fill department stores. These stores were inventing the culture of shopping, a new national pastime.

In Paris, couturier Paul Poiret was commissioning limited edition albums by artists such as Paul Iribe (1883-1935). In 1908, Iribe introduced figures printed using the pochoir method, based on Japanese techniques which involved creating a stencil for each layer of color which was then applied by hand. Known for his jeweled-tone palette and clean graphic line, Poirot now aligned his new uncorseted and exotic silhouettes with the elite and exclusive world of art.

Fig. 7. Paul Iribe, Les Robes de Paul Poiret Racontée, 1908

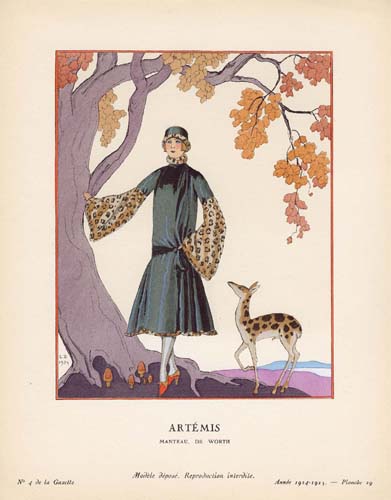

Published from 1912 to 1925, the luxury French magazine Gazette du bon ton brought together a group of young artists who were given unprecedented freedom in their interpretation of fashion. Each edition contained up to ten color pochoir plates and several croquis design sketches. Iribe was one several fashion illustrators who contributed to the celebrated publication that also included work by such greats as Charles Martin (1848-1934), Eduardo Garcia Benito (1892-1953) George Barbier (1882-1932) Georges Lepape (1887-1971) and Umberto Brunelleschi (1879-1949). The plates they produced for the Gazette show the influence of Japanese wood-block prints as well as the new sleek geometry of Art Deco styling.

Fig. 8. George Barbier, Artémis - Manteau, de Worth, plate 29 from Gazette du Bon Ton, No. 4, 1924-1925

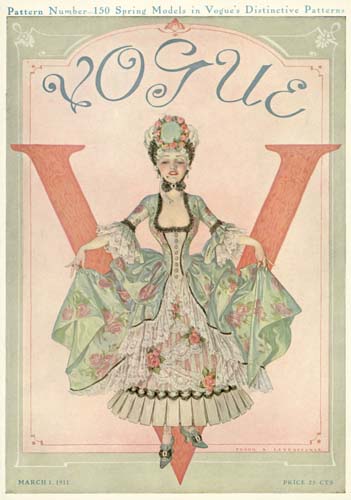

In the United States, mass-market fashion magazines Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar covered the social scene as well as contemporary clothing trends and beauty. Harper’s Bazaar signed an exclusive contract with Erte which lasted from 1915 to 1938—one of the longest contracts in publishing history. From 1910 until the outbreak of World War II, the cover of Vogue always featured an illustration. Vogue’s early covers displayed artwork created by American illustrators Helen Dryden (1882-1972), George Wolf Plank (1883-1965), Georges Lepape (1887-1971), and F.X. Leyendecker (1876-1924). Following the First World War, they were joined by European artists including Eduardo Benito (1891-1981), Charles Martin (1884-1934), Pierre Brissaud (1884-1964), and Andre Marty (1882-1974).

Fig. 9. F.X. Leyendecker, Cover of Vogue, March 1, 1911

THE GOLDEN AGE OF FASHION ILLUSTRATION

The 1920s and ‘30s represent the “golden age” of fashion illustration. Every commercial artist was considered a fashion artist—all were consummate draughtsmen. Many were able to represent the texture, sheen, and even weight of the fabric with authority and conviction.

New technological developments in photography and printing began to allow for the reproduction of photos to be placed directly onto the pages of magazines, meaning the fashion plate was no longer a representation of modern life. By the beginning of the 1930s, photographs began to be preferred in magazines, with Vogue reporting in 1936 that photographic covers sold better. Illustration began to be relegated to the inside pages.

_Red_Suit__Conde_Nast_January_1950.jpg)

Fig. 10. Rene Bouché, Red Suit, 1950

With the economic recession that followed the Stock Market Crash of 1929, the United States fashion industry grew less dependent on Paris for fashion. American garment manufacturing made great strides during the interwar years, improving large-scale production methods and standardizing sizing. Middle-class women relied on skillful dressmakers to interpret the latest couture designs at more affordable prices, while the patterns published by magazines such as Vogue and Women’s Journal were invaluable for the home dressmaker. With the outbreak of World War II, these skills assumed a new importance as women struggled to maintain some level of fashionability in the face of severe supply shortages and restrictions.

The prime objective of Vogue was to show fashion to the reader in as much informative detail as possible. Photography had freed illustrators from the need to make an exact record of the clothing in favor of more interpretive renditions of fashionable dress. The magazine publishers were said to complain that ‘the artists were chiefly interested in achieving amusing drawings and decorative effects...they were bored to death by anything resembling an obligation to report the spirit of contemporary fashion faithfully.” Vogue and Harper's Bazaar kept the art of fashion illustration alive, featuring the work of fashion illustrators like Christian Berard (1902-1949), Eric [Carl Erickson] (1891-1958), Erté [Romain de Tirtoff] (1892-1990), Marcel Vértes (1895-1961), Rene Bouché (1906-1963), and René Gruau (1908-2004).

Dior’s “New Look” in the late 1940s provided the inspiration for the fashion revival after the war. In many ways it was a retrograde style, harking back to the past rather than anticipating the future, yet it also symbolized a return to more cheerful, optimistic times.

Fig. 11. Erté, Symphony in Black, 1983

THE DEMISE AND REVIVAL OF FASHION ILLUSTRATION

By the 1950s, fashion editors were investing more of their budgets for editorial spreads of photography. The subsequent promotion of the fashion photographer to celebrity meant that illustrators had to be content with working on articles for lingerie and accessories, or in advertising campaigns.

The 1960s saw the continuing demise of fashion illustration in magazine publishing, which was featured in the new category of youth-oriented teen magazines, a number of which launched in the 1960s and all of which used illustration as a cheaper alternative to photography. Their role was to inspire and suggest, rather than dictate. Illustrated covers were occasionally featured, and editorial illustration was included by artists such as Rene Bouché, Alfredo Bouret (1928-2018), Tod Draz (1943-1987), and Tom Keogh (1922-1980).

Fig. 12. Alfredo Bouret, Illustration for Vogue Paris, 1960

Antonio Lopez (1943-1987) was the only artist regularly featured in the pages of Vogue during this time, having started his career at Women’s Wear Daily.

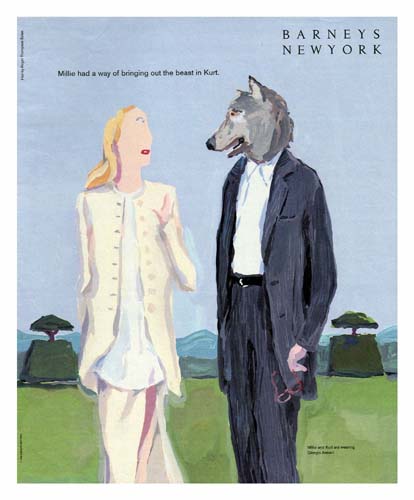

During the second half of the twentieth century, fashion illustration struggled to survive, until it underwent a renaissance in the 1980s. A new generation of artists was given an outlet in magazines such as La Mode en peinture (1982), Conde Nast’s Vanity (1981), and Visionaire (1991). Credit for this revival is attributed to advertising campaigns, notably Barney’s New York’s 1993-1996 advertising campaign with witty illustrations by Jean-Philippe Delhomme (b.1959).

Fig. 13. Jean-Philippe Delhomme, Advertisement for Barneys New York, 1993-1996

FASHION ILLUSTRATION TODAY

Falling between fine and commercial art, fashion illustration has only recently been reevaluated as a significant genre in its own right. Since beauty and grace are now outmoded both in fashion and in art, fashion drawing seems at times like a throwback to an earlier era. With photography so much more adept at documenting a garment’s details, the illustrators’ focus was no longer on the accurate rendition of the garment, instead interpreting the clothing and the person who might wear it. This developed a wide range of unique artistic styles in the late twentieth and early twenty first centuries, bolstered by digital tools and social media platforms. The 1990s saw the rise of computer-based drawing by such pioneers as Ed Tsuwaki (b.1966), Graham Rounthwaite (b.1970), Jason Brooks (b.1969), and Kristian Russell.

Fig. 14. Jason Brooks, Illustration for Revlon, 2013

This period, which saw the emergence of computer design programs Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator, also witnessed a revitalization of traditional art-based forms of fashion illustration. New York’s Parsons School of Design and FIT began offering illustration as a dedicated element of their fashion curriculum. “Traditional” hand-worked illustration has continued to enjoy a revival, with fashion illustrators often looking back to the masters of the past for stylistic inspiration. Fashion illustration that is grounded in classic methods has managed to survive alongside those created by more modern processes.

Most recently, illustration has come into vogue through collaborations between fashion designers and illustrators. With the use of social media, fashion illustrators are beginning to make their way to the spotlight. Bursting with vibrant colors, intricate patterns, and endless personality, fashion illustrations never fail to impress.

__60_60_c1.jpg)