HANNA-BARBERA: THE ARCHITECTS OF SATURDAY MORNING

In business together longer than most marriages, two men from very different backgrounds created an animation powerhouse that would come to dominate Saturday morning television. Partners for over 60 years, William Hanna and Joseph Barbera possessed a relationship that would last through the rise and fall of two cartoon studios and the creation of thousands of characters and hundreds of animated and live-action TV shows, films, and specials. In addition to receiving commercial and critical acclaim, their ground-breaking animation work was recognized with seven Academy Awards (and eight additional nominations), eight Emmys, and numerous other awards.

.jpg)

Together, animators Hanna and Barbera created one of the most memorable cartoons in history—Tom and Jerry. During the rise of television in the 1950s when film studios ceased producing cartoons, Hanna and Barbera saved the field of animation through talent, innovation, and hard work. At a time when General Motors sold 50% of all cars in the United States, the television program 60 Minutes referred to Hanna-Barbera as “the General Motors of animation.” As it turned out, Hanna-Barbera would eventually go even further by producing nearly two-thirds of all Saturday morning cartoons in a single year. (Barbera, Joseph R. My Life in ’Toons, p.55)

They weren’t like any other studio putting out media for the masses. Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera set out to entertain children and adults and ended up creating an experience called “Saturday Morning Cartoons.” Through laughter and imagination, they have amused and inspired millions of children for more than three generations. William Hanna and Joseph Barbera are the Architects of Saturday Morning.

1937-1960:

THE RISE OF TOM AND JERRY AND THE DECLINE OF ANIMATED SHORTS

A cat and a mouse! How unoriginal can you get?

—MGM animators to Joseph Barbera, My Life in ‘Toons, p.73

Like the cat and mouse duo that made them famous, William Hanna and Joseph Barbera could not have been more unalike. William Hanna was a shy Boy Scout and an all-American outdoor enthusiast born and raised in the American Southwest. Joseph Barbera was a suave and outgoing Brooklyn-raised son of Sicilian immigrants. According to veteran Hanna-Barbera writer Tony Benedict:

They were quite different. Bill had a white Lincoln Continental. Joe had a shiny new black Cadillac—a new one every year. Joe was dark and sun-tanned, Bill was white. Joe always had tailor-made suits and had his initials on his tie and cufflinks. Bill had none of that. Joe lived up in Bel Air and Bill lived in a little studio house in Sherman Oaks. Bill was a hard-nosed businessman who ran a tight ship. Joe was more persuasive and humorous—he had a more engaging personality and he had a fantastic sense of humor. (Benedict, Tony. Personal interview. 22 April 2016)

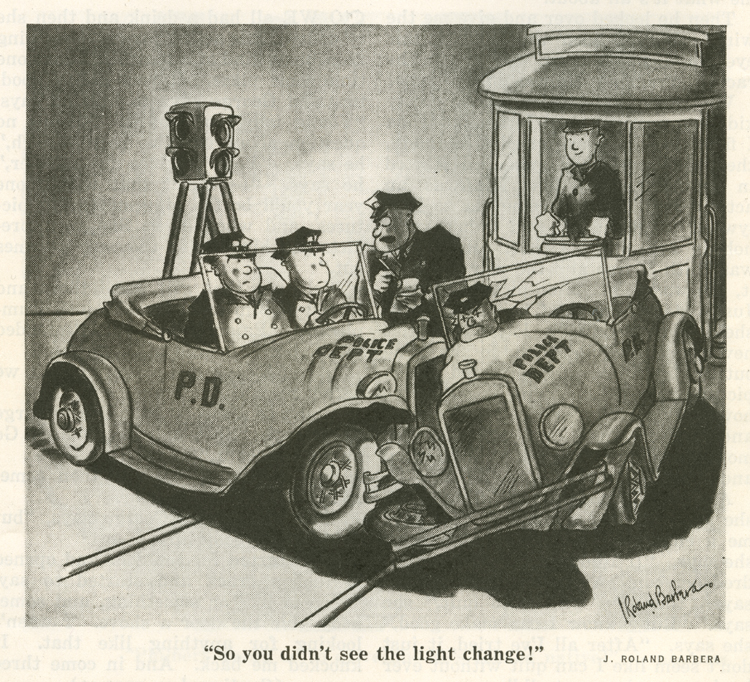

Barbera began his professional career as a tax accountant at Irving Trust Bank on Wall Street, where he worked from 1928 to 1934. His salary was a decent $25 per week, which was nearly the average salary at the time. However, frustrated by having to spend his nine-to-five days calculating and filing hundreds of tax returns for accounts in trust, Barbera took to drawing in his off hours. After creating some portraits for which he was paid $5 each, Barbera began drawing cartoons which he submitted to popular publications like Collier’s Weekly, Redbook, Ladies’ Home Journal, and The Saturday Evening Post. After numerous unsuccessful submissions over a period of two years, his artwork, signed J. Roland Barbera, was finally published in Collier’s Weekly alongside prominent illustrators such as William Steig, Harold Von Schmidt, Dr. Seuss, and Winsor McCay.

Fig. 1. Joseph Barbera, Cartoon printed in Collier's Weekly, September 15, 1934

Upon viewing Disney’s Silly Symphony short, Skeleton Dance, Barbera felt so inspired that he wrote a fan letter to Walt Disney, and included a drawing of Mickey Mouse. To Barbera’s great surprise, Disney responded that he would soon be in New York and would call him. Disney never did make the call, but Barbera remained enthralled with film animation and began taking drawing classes at the Art Students’ League and Pratt Institute, where he was introduced to an animator from Fleischer Studios, which was animating Popeye—the most popular cartoon of the 1930s.

Taking a two-week vacation from the bank to work at Fleischer, Barbera began in the painting department, coloring black and white paint onto cels. By the third day, he was promoted to inker, which required tracing the original drawing onto a cel with ink. Upon learning that a colleague had been doing that same job for three years at a salary of just $35 per week, Barbera quit the studio the following day. (Barbera, pp.40–41)

Three weeks after quitting work at Fleischer Studios (or three weeks and four days after starting at Fleischer), Barbera was let go from his job at Irving Trust due to the effects of the Great Depression. However, the following week Barbera interviewed for a position at Van Beuren animation studios where he was quickly hired. On his first day of work, animator Carlo Vinci, who would later work for Hanna-Barbera, helped the new hire learn the basics of creating animation drawings in sequence. Barbera worked as an in-betweener, which meant that if an animator creates drawings 1, 5, and 9 in a sequence of nine drawings, and the assistant animator draws drawings 3 and 7, Barbera would draw 2, 4, 6, and 8. Barbera continued with Van Beuren until their distributor, RKO, accepted a deal to distribute for Walt Disney, effectively ending the Van Beuren Studio. (Barbera, pp.46–47)

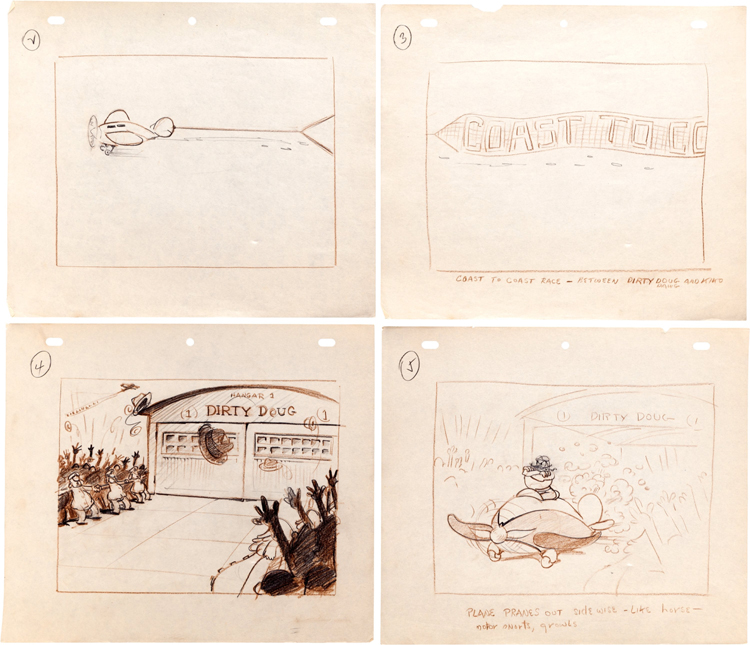

After making plans to travel to Los Angeles where he hoped to find work with Walt Disney, Barbera first made a stop at the New Rochelle, New York studio of Paul Terry, who had branded his cartoons “Terrytoons,” and would soon create his biggest hit in Mighty Mouse. Barbera briefly worked as an animator before aspiring to become more involved in the story-making part of animation. He presented his very first storyboards, featuring a pilot named Dirty Doug, to Paul Terry, who was not impressed. While at the studio, Barbera became friends with co-workers Dan Gordon and Harvey Eisenberg, who would later work for him at Hanna-Barbera. After seven months of dissatisfaction at the studio, Barbera chose to head west for MGM.

Fig. 2. Joseph Barbera’s first storyboards, created for Terrytoons, ca.1936

William Hanna’s career began at the Harman-Ising animation studio in 1930 in Los Angeles. However, rather than painting cels or drawing storyboards, his job consisted of emptying trash cans and washing animation cels for re-use. Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising had worked with Walt Disney in Kansas City in the early 1920s and moved with him to Los Angeles to start his studio. By 1929, they had parted ways with Disney to create their own studio.

Within just a few weeks, Harman and Ising promoted Hanna from janitor to head of the inking and painting department. Enjoying the company of his supervisors, Hanna often stayed after hours to work with Ising on animated shorts, contributing gags and comical situations. He also began timing cartoons, a task at which he excelled. He recalled, “In studying the markings on the metronome, I was able to determine that when the metronome clicked at a rate of 144 beats per minute, every beat represented ten frames of film. Using the index of twenty-four frames a second in animation movement, I figured that a twelve beat was half of that, so every time it clicked it would be twelve frames. Using that multiple I marked on my metronome for a ten beat, twelve beat, fourteen beat, sixteen beat, and so on to setting the tempo of, for example, a character’s walk by coordinating the action in frames to the beat of the metronome.” (Hanna, William D. A Cast of Friends, p.23)

In 1933, Harman and Ising had signed a deal with MGM to produce animation. Hanna continued to work alongside the two men, mastering every skill required to produce and direct animated shorts. Grateful for Hanna’s years of dedication with the company and assured of his skill, Harman and Ising offered Hanna a chance to direct his first animated short. To Spring debuted in 1936 and details in vivid Technicolor the fantastical world of underground-dwelling gnomes who are tasked with changing the season from winter to spring.

When Harman and Ising were released from their contract with MGM in 1937, Hanna chose to stay at MGM under the leadership of Fred Quimby, a former theater manager who was now head of the MGM animation studio and who was impressed with Hanna’s abilities. Hanna’s first assignment under the new leadership was the impossible task of creating a cartoon version of the popular comic strip, The Katzenjammer Kids, in collaboration with Warner Bros. veteran Friz Freleng. Retitled The Captain and the Kids, the cartoons never took off with audiences, partly due to the difficulty inherent in transferring the strong ethnic German accents of the characters from print to screen, but also because of the rising anti-German sentiment in the late 1930s.

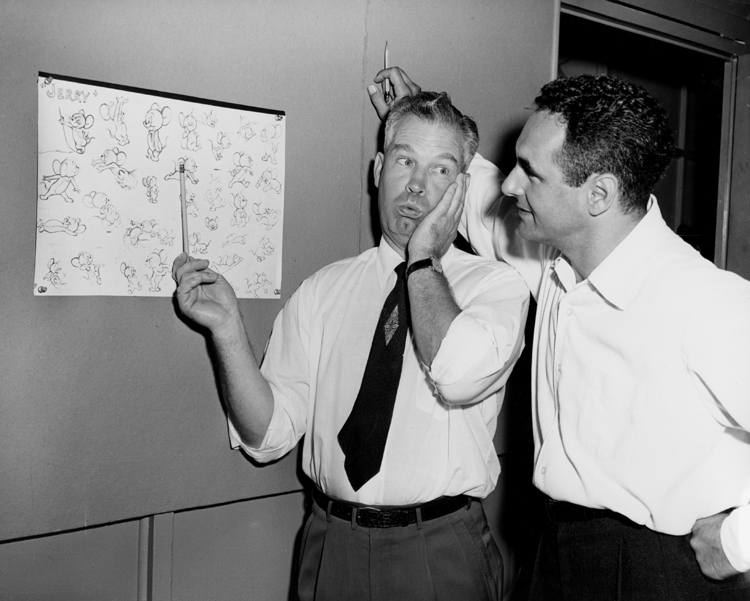

Once Quimby made the decision to cancel The Captain and the Kids, Hanna recalled, “Joe Barbera and I soon found ourselves sitting opposite each other in the story department…” (Hanna, p.39) Bored one day, Barbera asked Hanna, “Why don’t we do a cartoon of our own?” Barbera laid out some animation and Hanna timed it. It was a cat and mouse. Barbera recalled, “The minute you see a cat and mouse on the screen, you know it’s comedy.” While some of their colleagues loved the cartoon, their producer Fred Quimby was not amused, saying, “Don’t make any more of them—you don’t want to put all your eggs in one basket.” (TVLEGENDS. “Joseph Barbera—Archive Interview.” Online video clip. YouTube, 25 March 2008. Web.)

Fig. 3. William Hanna and Joseph Barbera at MGM, ca.1950s

Tom and Jerry’s auspicious cinematic debut was in the animated short Puss Gets the Boot (1940). This cartoon provided Barbera a chance to work again with his old friend from New York, Harvey Eisenberg, who created the layouts. Though recognizable as Tom and Jerry, the characters were named Jasper and Jinx in this cartoon. It wasn’t until the second cartoon, The Midnight Snack (1941), that Tom and Jerry received their now-famous monikers.

Producer Fred Quimby did not envision a future for Jasper and Jinx and opined (correctly) that cartoons featuring a cat and mouse were not a new idea. Fortunately for Hanna and Barbera, a Loews, Inc., distributor from Texas wrote to MGM following the release of Puss Gets the Boot, “inquiring when the studio was going to make more of ‘those delightful cat and mouse cartoons.’” (Hanna, p.43) According to Barbera, Quimby yelled out, “Hey fellas, make some more cat and mouse cartoons!” (TVLEGENDS. “Joseph Barbera—Archive Interview.”)

Puss Gets the Boot went on to win an Oscar nomination for Short Subjects, Cartoon, as did their third Tom and Jerry short the following year, The Night Before Christmas (1941). Of course, Quimby’s initial stance against Tom and Jerry did not prevent him from accepting seven Oscars awarded to Hanna and Barbera’s shorts over the next ten years, including four consecutive wins from 1943 to 1946. With William Hanna providing the only voice to either character in the form of Tom’s screams, Hanna and Barbera went on to direct 114 shorts featuring Tom and Jerry.

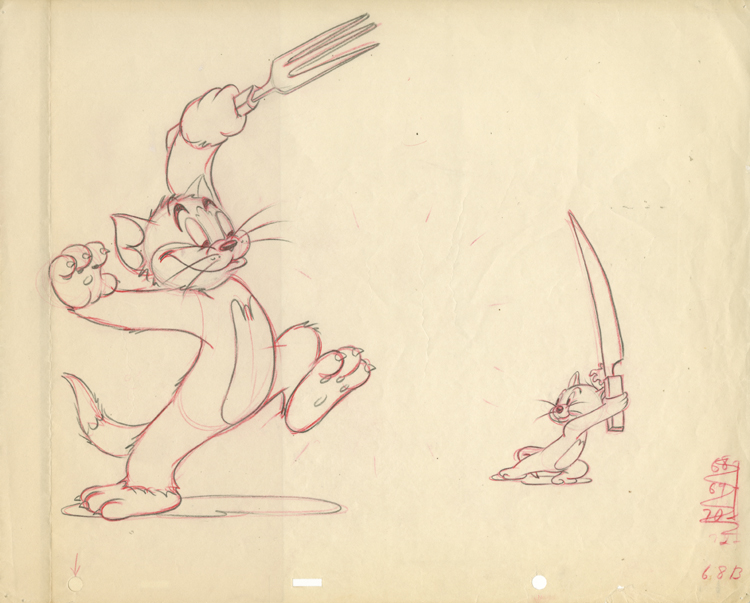

Fig. 4. Production drawing from the Tom and Jerry short Flirty Birdy, 1945

Perhaps it wasn’t merely the idea of re-using an old cat and mouse gag that made Quimby hesitant about emboldening Hanna and Barbera’s creativity. When the television program I Love Lucy began production in 1951, an agent called Hanna and Barbera asking them to animate the opening and interstitial segments of Lucille Ball’s new series (although in later syndication the animation was removed). Without Quimby’s knowledge, they agreed to work on the project after hours and began animating stars Ball and Desi Arnaz as stick figures. Upon viewing the animation, Barbera recalled, “Quimby called us down. He said, ‘Fellas, if you want to see the best stuff in animation, watch I Love Lucy.’ But we didn’t say a word.” (TVLEGENDS. “Joseph Barbera—Archive Interview.”)

In 1944, Gene Kelly approached Hanna and Barbera about working on the musical Anchors Aweigh, directed by George Sidney and starring Frank Sinatra and Gene Kelly. Pre-dating Mary Poppins’ penguin dance scene by several years, Hanna and Barbera were tasked with animating Jerry Mouse from Tom and Jerry to dance alongside a live-action Gene Kelly.

Barbera recalled, “… he really wanted as his dancing partner the world’s most famous mouse, Mickey, but Walt Disney turned him down flat. So he came back to his own studio, MGM, and to us. If he couldn’t have Mickey, Jerry would have to do.” (Barbera, p.97) Their collaboration with George Sidney on Anchors Aweigh paid dividends many years later when Sidney helped found Hanna-Barbera Enterprises.

Fig. 5. Film still featuring Jerry Mouse and Gene Kelly from the motion picture Anchors Aweigh, 1945

From 1946 to 1951, Barbera and Harvey Eisenberg published several comic books under the Dearfield Publishing label. The comic book titles were “Red” Rabbit, Foxy Fagan, Junie Prom, and Panhandle Pete and Jennifer. Barbera was under contract to MGM at the time, while Eisenberg had recently left MGM to illustrate comic books for another company. This required both men to keep their names off of the comic books’ masthead. Harvey Eisenberg’s son, Jerry, recalled, “They secretly produced these comics. My father said to me when I was a kid, ‘Please don’t say anything to any of your friends because this is secret because I’m under contract to Western Publishing and Joe is under contract to MGM.’” (Eisenberg, Jerry. Personal interview. 25 June 2016)

In 1953, Hanna and Barbera were again involved in motion pictures when they animated Tom and Jerry in an underwater sequence with swimming actress, Esther Williams, for Dangerous When Wet. That same year they re-teamed with Gene Kelly to create a sequence for Invitation to the Dance—Kelly’s directorial debut. Barbera recalled that the “Sinbad the Sailor” scene required them to create more than a mere cartoon on a live background, but “an entire animated world, in which the live action takes place.” (Barbera, p.98)

In 1955, Hanna and Barbera co-directed a remake of MGM’s 1939 anti-war short, Peace on Earth, in which a grandfather squirrel relates the history of war to his two grandchildren. Re-titled Good Will to Men for the modern version, the story used mice as the protagonists, while in an effort to update the tale, the cartoon was filmed in CinemaScope and contained images of newer weaponry that was used in World War II. Both versions were nominated for Academy Awards.

Hanna and Barbera were promoted to head MGM animation in 1955 after the retirement of Fred Quimby earlier that year. Unfortunately, for the two men who had strengthened the quality of animation at MGM over the last twenty years, the end of their time at the studio was drawing near.

The May 1948 Supreme Court case, United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., et al., signaled the demise of the Golden Age of Hollywood, the Studio System, and animated film shorts. The Court determined that movie studios were violating antitrust laws and could no longer be in the business of owning theaters. To make up for the lost revenue, studios began charging independent theaters more money to exhibit their films. However, theaters were no longer beholden to the studios for which films they could screen. Accordingly, studios moved to produce films that would turn a profit. In Adam Abraham’s book, When Magoo Flew: The Rise and Fall of Animation Studio UPA, he wrote, “Walter Lantz, who produced Woody Woodpecker’s films, noted that ‘exhibitors appreciate the entertainment value in cartoons and shorts, but they do not want to pay for them.’” (Abraham, p.205) B-movies, animated and live-action shorts, and newsreels began to disappear from movie screens. Thus began a major slump in the film industry that lasted until 1972.

The loss of theater revenue was only the first hit to the continued marketability of animated short films. The expansion of televisions into homes would also deal a heavy blow. In 1950, less than one in ten households owned a television, but within the next decade nine out of ten families would have one. The convenience of free (less the cost of an expensive set) in-home visual entertainment programming meant a further decrease in film attendance. (The cheapest TV in the early 1950s cost $289 or $2,700 in today’s dollars for a 17-inch black and white set. By the late 1950s, the same set was available for half the price.) Hanna recalled, “The differing complexions of the two markets were vividly evident. Television had become a daily and nightly viewing habit, while motion picture attendance became relegated to a periodic family ‘event.’” (Hanna, p.136)

Fig. 6. Production drawing from the Tom and Jerry short Flirty Birdy, 1945

The cost margin allotted to produce animated film shorts was much less than the cost of big-budget live-action films. According to Barbera, the animated shorts were the “only thing on the lot making money.” (TVLEGENDS. “Joseph Barbera—Archive Interview.”) Regardless, animation units were called upon to start closing beginning in the mid-1950s. Studio heads determined that they had enough canned animation sitting in their vaults to re-run the shorts in theaters and on television ad infinitum, and therefore the outlay of funds on production of additional shorts was unnecessary. Accordingly, they began to sell off their catalogues of animated shorts to television. Walter Lantz and Columbia sold many of their classic cartoons in 1954 with Terrytoons, Paramount, Warner Bros., and Universal following suit in late 1955. Wisely, Walt Disney chose to maintain control over his catalogue of shorts, which he would often broadcast on his mid-1950s ABC program Walt Disney’s Disneyland.

Upon the elimination of studio animation units such as 20th Century Fox in 1954 and MGM in early 1957, and Disney’s move away from creating new animated shorts in 1956, thousands of animators, writers, musicians, voice actors, cel painters, and in-betweeners—many of whom were only trained to work in the specialized field of animation—found themselves out of work.

After MGM’s animation unit closed its doors, director George Sidney became a silent partner in Hanna-Barbera Enterprises. His financing and clout in the industry helped turn Hanna and Barbera from out-of-work animators into the leaders of the world’s largest animation company. Especially significant was Sidney’s introduction of Hanna-Barbera to Screen Gems, the television division of Columbia Pictures, which would go on to syndicate Hanna-Barbera’s first television cartoons.

Academy Award wins and nominations of shorts directed by Hanna and Barbera at MGM:

1940 – Puss Gets the Boot (nominated); 1941 – The Night Before Christmas (nominated); 1943 – Yankee Doodle Mouse; 1944 – Mouse Trouble; 1945 – Quiet Please!; 1946 – Cat Concerto; 1947 – Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Mouse (nominated); 1948 – The Little Orphan; 1949 – Hatch Up Your Troubles (nominated); 1950 – Jerry’s Cousin (nominated); 1951 – Two Mouseketeers; 1952 – Johann Mouse; 1954 – Touché, Pussy Cat! (nominated); 1955 – Good Will to Men (nominated); 1957 – One Droopy Knight (nominated)

PLANNED ANIMATION

Joseph Barbera remembered, “Instead of $45,000 for five minutes like we had at MGM, we got $2,700. When we first sold Ruff and Reddy, Bill and I were taking in $40 a week for ourselves. I did the storyboards at home. My daughter Jayne colored in the drawings” (Digby Diehl, “Joe Barbera.” People, 16 March 1987: 69.Print.). “Limited animation saved the entire industry. Nobody was working.” (TVLEGENDS. “Joseph Barbera—Archive Interview.”)

The UPA animation studio, founded in 1943 by a group of former Disney artists, commonly used limited animation, or planned animation, as a visual device in their cartoons. Planned animation used fewer cels than full animation as practiced by Disney. For a standard Disney feature, the film would be projected at the standard 24 frames per second with each frame having different animation. Planned animation provided for fewer frames, so that instead of each frame having a new image, frames would be repeated two or three times, resulting in just twelve or eight different frames per second.

This experimental approach is showcased in UPA’s most stylized cartoon, Gerald McBoing Boing, for which they won an Academy Award in 1951. However, Hanna-Barbera adapted the technique out of necessity. While film shorts could take several months and cost tens of thousands of dollars, television animation required a much quicker production schedule with a markedly reduced budget. Kenneth Muse, former colleague of William Hanna and Joseph Barbera at MGM animation, worked diligently to perfect the technique for Hanna-Barbera to use on a much larger scale.

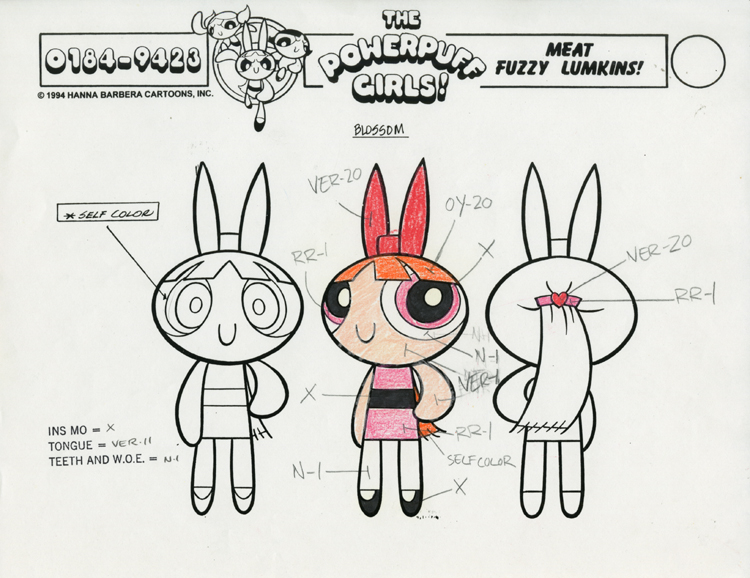

The reduced cost of planned animation vs. full animation was due to fewer cels, or fewer frames per second. This also meant using as much of a cel as possible to construct a scene. For example, instead of re-drawing Fred Flintstone’s head in every scene, they were able to keep running the same head cel, minus the mouth, through several different frames and simply overlay different mouth cels on his head every time he moved his mouth.

One subtle side effect of the early years of planned animation was “ring around the collar”—the tendency of Hanna-Barbera characters to be drawn with neckties and collars. According to Takamoto, “This was so the head could be easily separated onto its own cel without a seam line.” (Takakmoto, Iwao. My Life with a Thousand Characters, p.90) When possible, animators would draw characters like Fred Flintstone and Barney Rubble with five o’clock shadows to further reduce animation.

Fig. 7. Production cel setup from Yogi’s Gang, 1973

Just because planned animation cost significantly less than full animation did not mean the quality of the cartoons suffered, though more effort was needed in other areas. The writing had to be better scripted, the gags had to be funnier, the cameraman had to be more creative, and the sound effects more expressive. By favoring characters, story, and timing over the visual aspect of animation, Ward Kimball, one of Disney’s legendary team of “Nine Old Men,” observed, “Limited animation can be the best way to put across a humorous idea.” (Abraham, p.233) As Iwao Takamoto noted, “…the poses had to be extremely accomplished and funny in and of themselves. That takes a lot of talent…” (Takamoto, p.92)

HANNA-BARBERA’S EARLY YEARS

“Get set, get ready—here come Ruff and Reddy!”

–The Ruff and Reddy Show theme song

On the morning of Saturday, August 19, 1950, for the first time in history, children turned on their family television sets to find two shows that were meant just for them. Airing on ABC, Acrobat Ranch was hosted by Uncle Jim and featured circus acts performed by Tumbling Tim and Flying Flo, and Animal Clinic presented live animals with information that was aimed at a younger audience. TV was typically thought to be intended for family viewing, and it was unusual to see a show directed at young viewers. However, since it was determined that adults watched the least amount of television on Saturday mornings, it appeared to be an ideal time to air child-centered programming. (Mittell, Jason. Prime Time Animation, p.51)

As film studios had ceased production of animated shorts and theaters had stopped requesting animated shorts for exhibition, television distribution companies began seeking out the studios’ libraries of old cartoons. In November 1955, Paramount sold their library of 1,800 shorts, including ones starring Little Lulu and Betty Boop, to a distributor for $3,600,000. The following month, CBS purchased the Terrytoons cartoon library from Paul Terry, Barbera’s old employer, for $5,000,000, including characters such as Heckle and Jeckle and Mighty Mouse. Using this material, CBS began airing the first Saturday morning cartoon series. The Mighty Mouse Playhouse debuted on CBS in December 1955 and would remain on the air through 1966.

In his book Prime Time Animation, author Jason Mittell notes, “Not all cartoons migrated to television unchanged however… some of the cultural content was deemed troubling for recirculation. Most famously, a number of shorts with explicit racial stereotyping… never made it to television… Other cartoons produced during World War II were not shown on television, due to both their racist and anti-Japanese content…” Mittell also outlines the changes that occurred to Hanna and Barbera’s Tom and Jerry cartoons: “[they] were regularly changed for television, transforming the character of a black maid, Mammy Two Shoes, into an Irish maid by re-dubbing her voice and recoloring her legs and arms (all that was seen of the character) white…” Furthermore, he writes, “Images of violence deemed excessive, characters smoking or drinking, and representations of guns, were all edited from Disney, Warner Bros., and MGM shorts when appearing on television.” (Mittell, p.37) However, for historical importance many of these cartoons have now been restored to their original form on DVD.

Once the word came down that MGM’s animation studio would be closing, Hanna and Barbera remained in the office for a few months. According to author Michael Barrier, “Hanna and Barbera had developed the idea for [The Ruff and Reddy Show] ‘on the side’ during their last year at MGM… and tried to talk MGM into a half-hour show…” However, MGM executives were cutting costs in animation at that time and were not interested. Instead, director George Sidney introduced them to executives at Screen Gems television distribution who were interested. Hanna recalled, “So we formed a partnership and they wanted us to take in some of the Cohn boys (Harry Cohn’s relatives) and George [Sidney]. They were part of the original Hanna-Barbera company.” (Barrier, Michael. Hollywood Cartoons, pp.560-561)

Upon forming Hanna Barbera Enterprises in 1957, the founders began setting up shop at the old Charlie Chaplin Studios on LaBrea Avenue in Hollywood. Hanna and Barbera recruited the best writers and artists in the business. Because of mass layoffs in the industry, they were able to hire seasoned veterans like Michael Maltese, Warren Foster, Dan Gordon, Tony Benedict, Art Scott, Willie Ito, Kenneth Muse, Alex Lovy, and Carlo Vinci. Additionally, many Disney employees were laid off after Sleeping Beauty ended production and were now available for work at Hanna-Barbera. Many of these men were responsible for Hanna-Barbera’s most memorable cartoons, including The Huckleberry Hound Show, The Yogi Bear Show, The Flintstones, The Jetsons, and Quick Draw McGraw.

At the time that Hanna-Barbera began producing cartoons for television, Saturday morning shows were often serials, such as The Lone Ranger, The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin, and Sky King, or hosted variety shows that were produced within local markets. Cartoon shows were almost completely filled with recycled film shorts that were separated by hosted segments. Such was the case with Hanna-Barbera’s first television series, The Ruff and Reddy Show, which featured friends in the form of a cat (Ruff) and a dog (Reddy). With episodes running only seven minutes long, beginning in December 1957 it was syndicated into markets where it was included in shows with other cartoons that were introduced by a host.

Fig. 8. Series title cel from The Ruff and Reddy Show, ca.1957

Barbera recalled, “What was needed to make Ruff, Reddy, and the other characters come alive were great voices… If you don’t have the right voices, you don’t have a cartoon. Fortunately, in casting Ruff and Reddy, we immediately discovered two great voice actors, Daws Butler and Don Messick.” (Barbera, pp.118–119) Daws Butler would continue with Hanna-Barbera until his death in 1988. Messick remained with the company until shortly before his death in 1997.

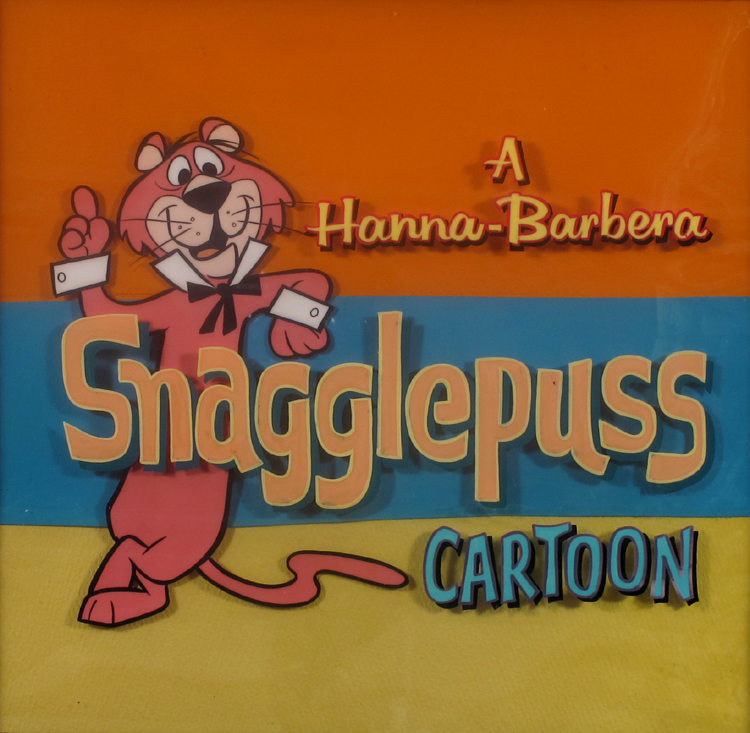

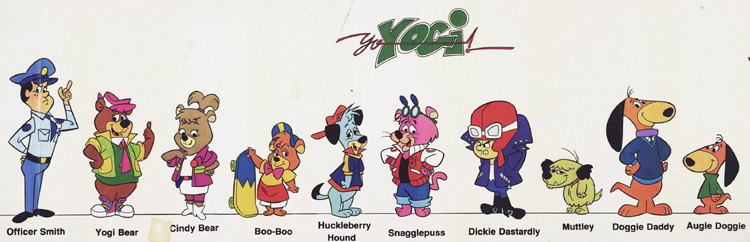

Butler provided the voices for dozens of Hanna-Barbera’s cartoons through the years, including many of their most popular characters. In addition to being the voice behind Huckleberry Hound, Yogi Bear, Hokey Wolf, Quick Draw McGraw, Snagglepuss, Elroy Jetson, Wally Gator, Peter Potamus, and numerous others, he also filled in for Mel Blanc as Barney Rubble for five episodes of The Flintstones while Blanc recovered from an auto accident.

Messick’s most famous voice was that of Scooby-Doo, for which he performed the role from the character’s debut in 1969 until he retired from the role in 1994. He also provided the voices for Boo Boo Bear, Ranger Smith, Bamm-Bamm Rubble, Astro from The Jetsons, Dr. Benton Quest, Ricochet Rabbit, Atom Ant, Muttley, and many more.

From the very beginning, Hanna and Barbera possessed the foresight to produce all of their television cartoons in color, even though none of the networks were broadcasting in color and it would be years before the first cartoons were aired in color. “Joe [Barbera] and I could see color programming looming on the television horizon,” said Hanna. (Hanna, p.83) Also, if television didn’t pan out, the color Hanna-Barbera cartoons would be readymade for exhibition in theaters.

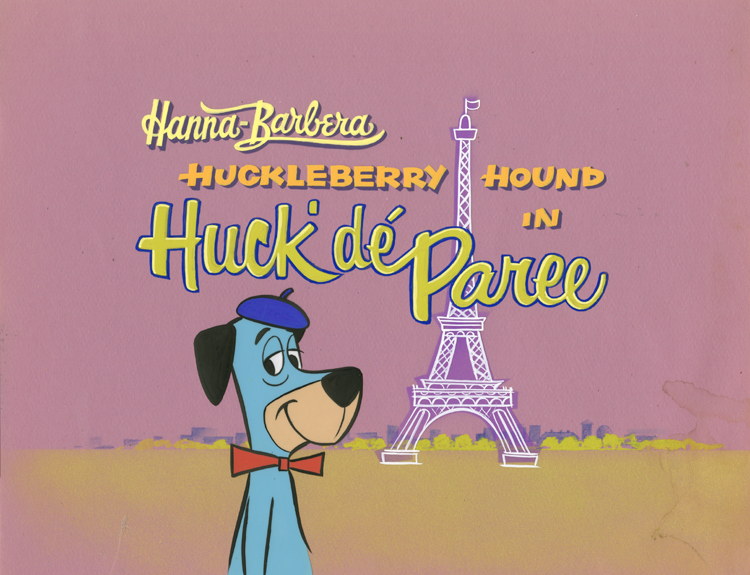

Debuting in 1958, The Huckleberry Hound Show became the first half-hour animated series without a host. (Culhane, John. Hanna-Barbera 25 Years, p.3) Huckleberry Hound was a blue hound dog from the southern United States who held a different job in nearly every episode. His laconic southern drawl symbolized his easy-going attitude. There was no problem that could upset Huckleberry Hound and no conflict too great to overcome. When trying to create the voice for Huckleberry Hound, Barbera asked Butler to recite the character’s lines in a southern accent. Butler replied, “Well, there’s at least ten distinct dialects I know. There’s South Carolina and there’s North Carolina. There’s Tidewater, Piedmont, and Hill Country. There’s the Georgia cracker dialect and the Florida swamp country accent. In Louisiana, you get the Creole Influence…” (Barbera, p.123)

Fig. 9. Title cel and background painting setup for The Huckleberry Hound Show episode Huck dé Paree, 1961

Another segment on The Huckleberry Hound Show featured a hungry ursine resident of Jellystone Park. Accompanied by his smaller pal Boo Boo, Yogi Bear schemed every week to sneak past Ranger Smith and abscond with a poor park visitor’s “pic-anic basket.” Though he proclaimed himself “smarter than the average bear,” Yogi’s schemes never seemed to pan out. However, his popularity among viewers rewarded him with his own series in 1961, The Yogi Bear Show, and the first Hanna-Barbera feature film, Hey There, It’s Yogi Bear, in 1964.

Fig. 10. Color model cel of Yogi Bear, 1990

Animation historian Michael Mallory recalls, “Yogi also had the distinction of being the favorite character of Bill Hanna. Bill made this confession to me in 1998, a time when he was suffering from Alzheimer’s Disease, which wreaked havoc on his short-term memory. His long-term memory, however, was still on call, so much so, in fact, that he sang the entire theme song to Yogi Bear for me. He knew the lyrics well because he had written it.” (Mallory, Michael. “More Enduring Than the Average Bear,” Animation Magazine, 1 February 2013, Animationmagazine.net)

“I hate meeces to pieces!” was a phrase frequently shouted by Mr. Jinks, a character in Pixie and Dixie, the third segment of The Huckleberry Hound Show. Sharing a similar plot base as Tom and Jerry, Mr. Jinks was a cat who frequently butted heads with mice Pixie and Dixie, though their relationship was much friendlier than that of their predecessors.

Hanna-Barbera’s use of catchphrases is a defining feature of their cartoons. Just as a great advertising slogan can solidify an emotional attachment to a product—Brylcreem’s “A little dab’ll do ya” for the older crowd and the campaign “Got Milk?,” which featured a rotating slate of celebrities, for the younger audience—a catchphrase can instantly bring to mind a cartoon character. A good catchphrase will become part of the zeitgeist for generations, reaching through all segments of society. As “I Yam What I Yam” and “What’s Up, Doc?” became the defining catchphrases for Popeye in the 1930s and Bugs Bunny in the 1940s, Hanna-Barbera’s catchphrases would quickly become part of the American consciousness. “Yabba-Dabba-Doo!,” “Smarter than the average bear,” “Heavens to Murgatroyd!,” “Scooby-Dooby-Doo!,” “Captain CAAAAAVEMAAAAAAANNNN!,” and “Wonder Twin Powers, Activate!” are just a handful of the studio’s catchphrases that made an impression in popular culture at the time and continue to evoke the memory of beloved cartoon characters.

After the debut of The Huckleberry Hound Show, Hanna and Barbera were surprised to learn that over 40% of that series’ audience was comprised of adults. In fact, bars would advertise Huckleberry Hound happy hours during the airing of the program. (Mittell, p.42) Barbera recalled, “In one San Francisco bar favored by the college crowd, the barkeep would ring a bell at six on the evening when the show was aired and direct the patrons’ attention to a sign that announced: NO TINKLING OF GLASSES OR NOISE DURING THE HUCKLEBERRY HOUND SHOW.” (Barbera, p.127) This data on public receptivity toward their cartoons persuaded the partners to begin thinking about bringing animation into prime time.

Fig. 11. Carl Iwasaki, Bar patrons watching Huckleberry Hound, 1959

1960-1966:

HANNA-BARBERA IN PRIME TIME

Following on the surprise success of their cartoon series among adults, in 1960 Hanna and Barbera set out to create an original adult-oriented prime time cartoon series, something that had never been done. Barbera recalls that the idea for The Flintstones took some time to develop. They considered introducing various types of characters throughout history—Pilgrims, hillbillies, Romans, Native Americans—before ultimately deciding on cavemen. (TVLEGENDS. “Joseph Barbera—Archive Interview.”)

Fig. 12. Concept painting for The Flintstones, ca.1960

A prime time cartoon aimed at adults was a hard sell in 1960. After eight long weeks of living in hotel rooms from New York to Chicago and acting out scenes from the storyboards he presented in front of dozens of sponsors as well as to NBC and CBS, ABC was Barbera’s last shot. Fortunately, because ABC was at a disadvantage with NBC and CBS and could never catch up in ratings, they took a chance with The Flintstones.

“The program was Hanna-Barbera’s attempt to capitalize on the adult audiences for their syndicated programs, and ABC primarily targeted an adult audience as well.” (Mittell, p.45)

In order to write for an adult audience, for a cartoon that was inspired by The Honeymooners, Barbera brought in an actual writer from The Honeymooners. However, Barbera soon discovered that he just could not write for animation. “He was terrible. [There were] no visual gags, no chasing, no nothing, just dialogue.” From then on, Barbera decided to rely on his in-house team of writers for the series. (TVLEGENDS. “Joseph Barbera—Archive Interview.”)

Prior to the airing of The Flintstones, Hanna and Barbera were forced to deal with the threat of legal action from the creator of the “Hi and Lois” comic strip, Mort Walker. The original name for The Flintstones was The Flagstones. Walker was upset that the name closely resembled the surname of his cartoon family —the Flagstons. Fred and Wilma then briefly became Gladstones before “Flintstones” finally won out. (Barbera, p.6)

The debut of The Flintstones in prime time in September 1960 was not well received by TV critics. The New York Times referred to The Flintstones as “an inked disaster.” The Baltimore Sun called it “not a very good [comedy] inhabited by unpleasantly uncouth people.” TV critic Jay Fredericks claimed, “I was solemnly assured by a local television official a couple of months ago that The Flintstones would be (a) hilarious and (b) THE show of the season. It is neither. The whole series is weak.” Thankfully, viewers prevailed and made The Flintstones a surprise success, finishing the season at number 18 in the overall Nielsen ratings and giving ABC a rare non-western hit. (Mittell, p.45) The viewing public would continue to follow the stone-age adventures of Fred Flintstone through 166 episodes over the next six years, and in a spy-themed feature film, The Man Called Flintstone, in 1966.

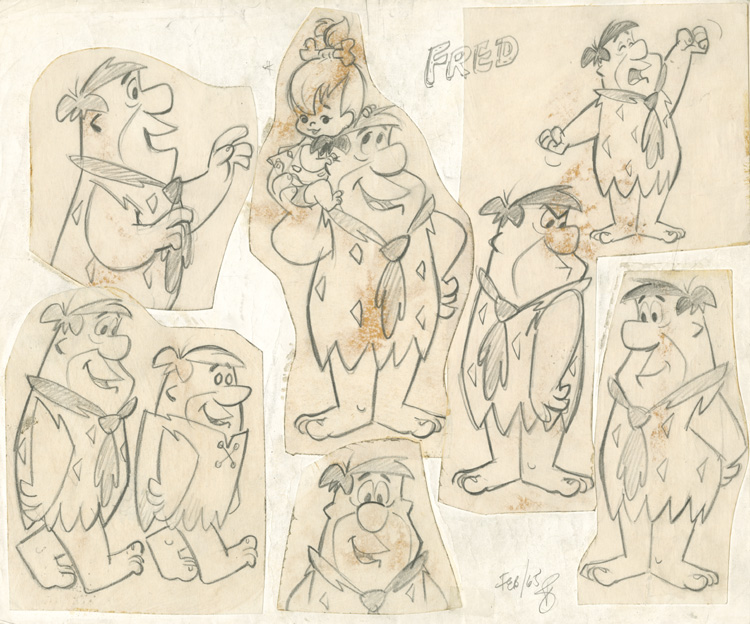

Fig. 13. Dick Bickenbach, Model sheet of characters from The Flintstones, 1965

From its inception, Hanna and Barbera had planned to include a child in the series. Early concept drawings and a single Flintstones Golden Book include references to Fred’s son, Fred, Jr. However, the decision was made to focus on the relationship between the husbands and wives and Fred, Jr. was dropped. In a bid to enliven the series in 1963, Hanna and Barbera planned to finally add a child to the Flintstones family. Thus, Fred and Wilma’s daughter, Pebbles Flintstone, was born in the Season 3 episode “The Blessed Event.” However, a female child had not always been the intended gender. Once it was announced that a baby would be joining the series, a merchandising agent called Barbera to see if it would be a boy or girl. Barbera later recalled, “What else would a Sicilian say… a boy! A chip off the old rock.” The agent remarked that was unfortunate because “If it was a girl we could have made a hell of a deal.” Barbera ended the call by correcting the agent, telling him, “It is a girl!” In the first two months on shelves, $3 million of Pebbles dolls were sold. (TVLEGENDS. “Joseph Barbera—Archive Interview.”)

Just as Tom and Jerry was borrowed from the “cat and dog” formula frequently used in early animated film shorts, it made good business sense to stick with tried and true successes. These are some examples of Hanna-Barbera’s inspirations through the years:

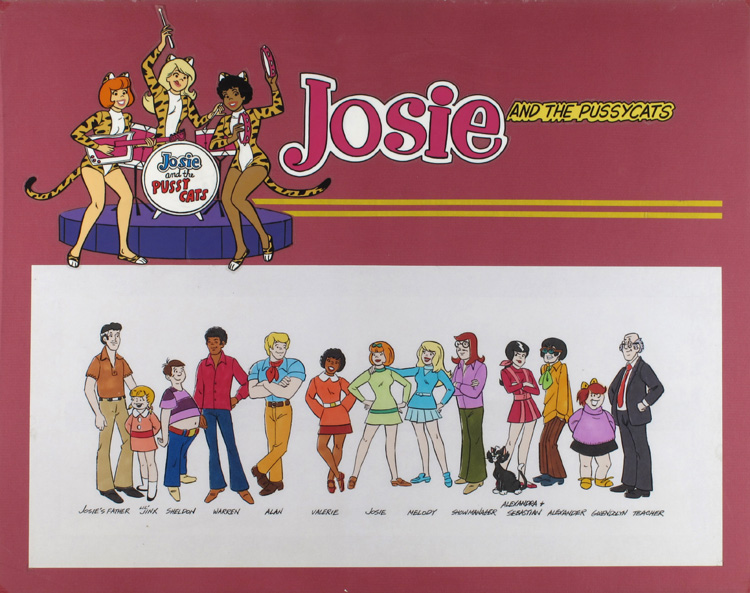

Ruff and Reddy from Tom and Jerry, Yogi Bear from The Honeymooners’ Ed Norton, Snooper and Blabber from Tom and Jerry, Top Cat from Phil Silvers, Wally Gator from Ed Wynn, the Jetsons from the Blondie film series, Secret Squirrel from James Bond, Penelope Pitstop from the damsel in distress motif from silent films, Scooby-Doo from Dobie Gillis, Jabberjaw from the film Jaws, Captain Caveman and the Teen Angels from Charlie’s Angels, Josie and the Pussycats from The Archies, and the Snorks from The Smurfs.

Perhaps the most famous instance of Hanna-Barbera borrowing an idea for a series came from comparisons of The Flintstones to The Honeymooners. Barbera admitted to being a fan of the earlier series, saying, “And from the beginning there have been no shortage of people to tell me that The Flintstones borrowed (or stole) very heavily from The Honeymooners—an observation (or accusation) I always take as the highest compliment possible, because The Great One [Jackie Gleason] really was, and The Honeymooners was a landmark in the history of television comedy.” (Barbera, p.7) William Hanna recalled, “I personally thought The Honeymooners was the funniest half-hour on television.” (Hanna, p.114)

The creator and star of The Honeymooners, Jackie Gleason, was well aware of the similarities between the two shows, especially how closely Alan Reed’s Fred Flintstone mirrored Gleason’s Ralph Kramden. In The American Family on Television, author Marla Brooks wrote, “Jackie’s lawyers told him he could probably have The Flintstones canceled if he wanted to, but in the same breath also asked, ‘Do you want to be known as the guy who yanked Fred Flintstone off the air? The guy who took away a show that so many kids love, and so many of their parents love, too?’ Apparently Jackie thought it over and decided to leave well enough alone.” (Brooks, p.54)

In addition, Mel Blanc’s voice work for Barney Rubble was so similar to that of Art Carney’s Ed Norton character on The Honeymooners that there was an inside joke among Hanna-Barbera staff that Barney Rubble rhymed with [Art] Carney Double.

When The Flintstones ended its run in 1966, there were no other animated prime time series until The Simpsons debuted in 1989, with the exception of the low-rated Hanna-Barbera cartoon Where’s Huddles?, which aired for just 10 episodes in 1970, and Wait Till Your Father Gets Home which ran for three seasons beginning in 1972. However, the Modern Stone Age Family would return to television numerous times over the next thirty years in various series on Saturday mornings.

With the first season of The Flintstones a hit among viewers, Hanna and Barbera made plans for a second prime time series. Top Cat featured a gang of alley cats led by Top Cat (or T.C.). Members of the group included Benny the Ball, Spook, Brain, Choo Choo, and Fancy-Fancy. The show was inspired by the 1950s television series The Phil Silvers Show, and Arnold Stang’s voice work for T.C. is unmistakably similar to Phil Silvers’ character Sergeant Bilko. As with many plotlines on The Phil Silvers Show, the felines on Top Cat were frequently involved in get-rich-quick schemes. Because of their shenanigans, Top Cat and his gang had regular run-ins with the policeman on the beat, Officer Dibble.

Fig. 14. Animator’s model sheet of characters from Top Cat, 1961

Airing on ABC Wednesday nights during the 1961 season, Top Cat is considered to be Hanna-Barbera’s first failure. Barbera recalled the first time he showed an episode to the Screen Gems executive, John Mitchell. Mitchell exclaimed, “What the hell is going on here? Where are the laughs? This isn’t a cartoon. You’re missing the cartoon laughs.” Barbera agreed, but it was too late to change things —several episodes were already completed. He remembered, “[Mitchell] was right. In one respect, we had made Top Cat look like the traditional theatrical cartoons…richer, fuller, more complex… [though] I had taken a fatal detour from cartoon tradition. The great mix of urban alley cat characters had generated a lot of nifty dialogue… [but] there were no cartoon sight gags. I had committed the very crime for which I had earlier junked The Flintstones scripts by that ex-Honeymooners writer.” (Barbera, p.145) ABC cancelled Top Cat after just one season.

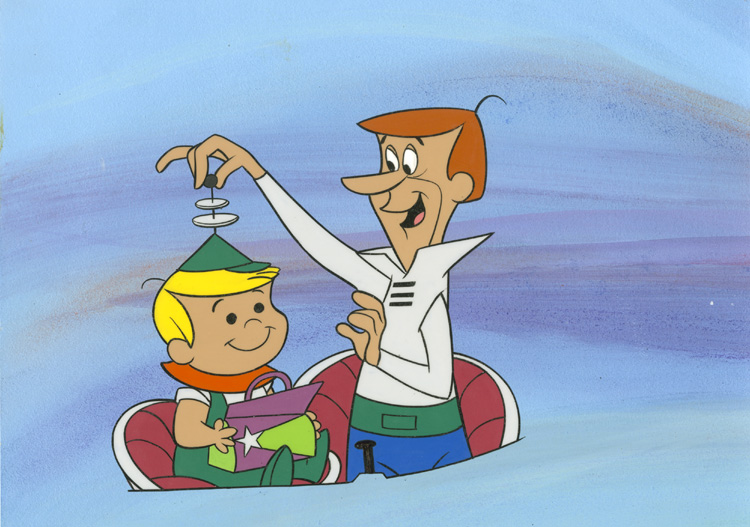

Ever the optimists, Hanna and Barbera were not discouraged by Top Cat’s demise and began working on a new prime time series involving a family in another era—this time placing them in the Space Age instead of the Stone Age. The Jetsons featured the patriarch George Jetson confronting the realities of being the sole breadwinner for a family that included his loving wife, Jane; a typical (for the 1960s) teenaged daughter, Judy; a genius-level inventor son, Elroy; a robot maid, Rosey (changed to Rosie in later series); and the family dog, Astro. George worked at Spacely Sprockets in Orbit City, where his job was to push a button on a computer named RUDI (Referential Universal Digital Indexer) for one hour a day, two days a week.

Fig. 15. Production cel and background painting setup from the opening sequence of The Jetsons, 1962

The series was a favorite of the writers and animators because the futuristic setting gave them the opportunity to include any inventions they could dream up, such as the familiar moving walkway and flying car that folded into a briefcase. Animator Jerry Eisenberg noted, “We weren’t bound by any particular rules… I loved designing backgrounds for [The Jetsons]. I remember when we were developing the series, Tony Benedict brought in a book one day. The title of it was 1975. Thirteen years in the future. It was an interesting book because it showed predictions of what there would be in 1975, new ideas, new appliances, whatever.” (Eisenberg, Jerry. Personal interview. 25 June 2016.)

Premiering in the fall of 1962, The Jetsons was the first program broadcast in color on ABC and was very popular with viewers. However, ABC placed the series in a time slot on Sunday nights against the established hit series Dennis the Menace on CBS and Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color on NBC. Barbera recalled, “It is a testament to the fundamental strength of The Jetsons that it wasn’t simply creamed by these shows. What did happen is that the Nielsen share split evenly into three virtually equal parts…” (Barbera, p.151) Unfortunately, only one season was produced, though The Jetsons would prove successful in syndication over the next twenty-two years.

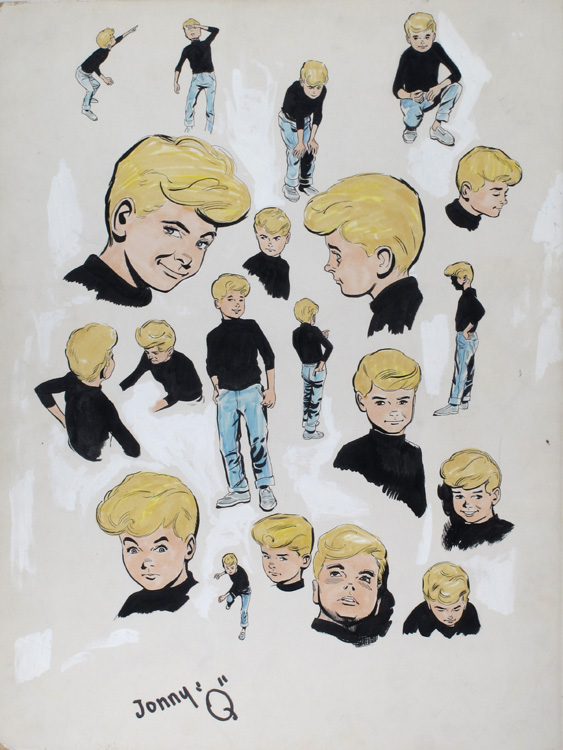

The 1964 debut of Jonny Quest would be the last prime time series Hanna-Barbera would introduce in that decade. Its theme, music, and overall design varied so greatly from previous Hanna-Barbera cartoons that its success would bring a change to the familiar Hanna-Barbera style.

BUILDING ON SUCCESS

Fresh on the heels of the successful series The Huckleberry Hound Show, which not only introduced Yogi Bear to the American public, but also won the first Emmy Award for an animated series, Hanna and Barbera were at the top of their game. The Quick Draw McGraw Show debuted in syndication in late 1959 and continued Hanna-Barbera’s formula of popular characters and well-crafted gags. The Flintstones hit the airwaves in September 1960 and became a pop culture juggernaut. Just a few months later, The Yogi Bear Show began airing in Syndication. Hanna-Barbera’s success seemed unstoppable. William Hanna remarked, “The decade of the 1960s was, in essence, the salad years of Hanna-Barbera. Most of my old friends and veteran colleagues remember them as an incredibly fruitful period of television production.” (Hanna, p.129)

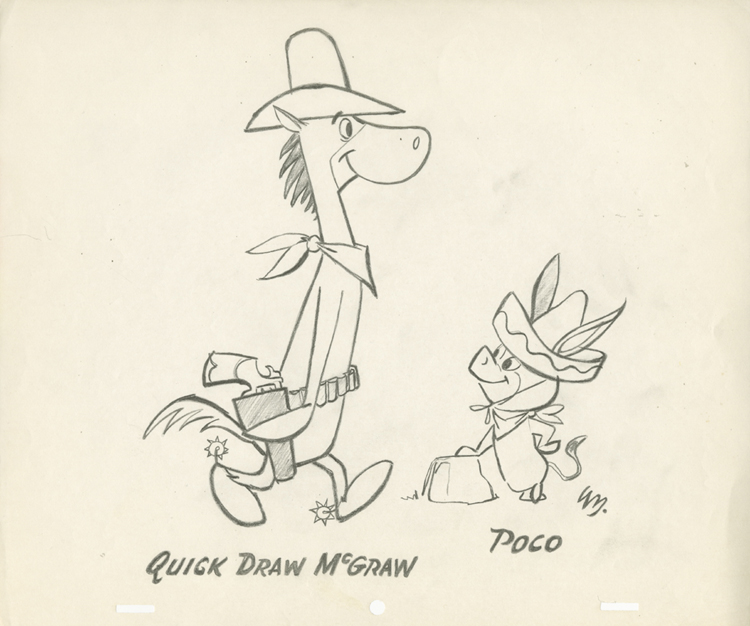

The Quick Draw McGraw Show found a new star in Quick Draw, an equine sheriff in the Old West. He pursued criminals accompanied by his deputy, a burro named Baba Looey. Quick Draw would occasionally be disguised as El Kabong, a Zorro-type hero who would bash villains on the head with his guitar (also known as his kabonger). Other segments included Augie Doggie and Doggie Daddy, a genuinely sweet cartoon about a relationship between father and son dachshunds, and Snooper and Blabber, a cat and mouse detective team. The Quick Draw McGraw Show would stay on the air for three seasons.

Fig. 16. Ed Benedict, Concept drawing of Quick Draw McGraw and Poco (later renamed Baba Looey), ca.1959

The Yogi Bear Show premiered in January 1961 with accompanying shorts Snagglepuss and Yakky Doodle. Snagglepuss was overly dramatic and flamboyant, a well-dressed pink mountain lion who could never get an even break. His catch phrases were “Heavens to Murgatroyd!” and “Exit! Stage Left!” Unlike most Hanna-Barbera characters, Snagglepuss did not have any partners in crime. Yakky Doodle, on the other hand, was a tiny helpless duck who sounded very much like Donald Duck, courtesy of voice actor Jimmy Weldon. Yakky’s only friend was a bulldog named Chopper who helped defend Yakky from Fibber Fox.

Daws Butler’s voice work for Snagglepuss, later recycled for The Funky Phantom, was not appreciated by Bert Lahr, who famously played the Cowardly Lion in The Wizard of Oz (1939). Lahr was concerned that the impersonation was so close that when Snagglepuss began endorsing Kellogg’s cereals, viewers would think it was his voice. According to the YOWP blog, “Radio-TV Daily reported in 1963 on a $500,000 lawsuit by Bert Lahr against Kellogg’s, Screen Gems, and Hanna-Barbera, because Daws Butler’s Lahr-inspired Snagglepuss was appearing in commercials for Cocoa Krispies.” (“How Daws Butler Played Snagglepuss.” YOWP, 30 April 2014, yowpyowp.blogspot.com) Both sides agreed that from that point on Kellogg’s would prominently list on the commercials that Daws Butler was the voice of Snagglepuss.

Fig. 17. Title card and background painting setup for Snagglepuss, ca.1961

In a sign of things to come, 1962 was the first year all three networks aired children’s programming on Saturday morning. The oddly titled The New Hanna-Barbera Cartoons debuted in syndication in September of that year. It was comprised of the cartoons Wally Gator, Touché Turtle and Dum Dum, and Lippy the Lion and Hardy Har Har. Wally Gator (Daws Butler doing Ed Wynn), concerned an alligator at a city zoo who believes the grass is greener on the other side, escaping the zoo in each episode but ultimately returning. Touché Turtle and Dum Dum depicted a fencing reptile and his sheepdog sidekick, and Lippy the Lion and Hardy Har Har followed the familiar themes of Yogi Bear and Top Cat as Lippy the Lion consistently ran into trouble with his hyena pal by his side.

The Magilla Gorilla Show first aired in January 1964 and included segments Magilla Gorilla, Ricochet Rabbit and Droop-a-Long, and Punkin’ Puss and Mushmouse. The star of the show, Magilla Gorilla, lived in the pet shop owned by Mr. Peebles, who excitedly sold Magilla at the beginning of each episode, only to have him returned by an unhappy owner. Similar to Quick Draw McGraw, Ricochet Rabbit was a sheriff in the Old West accompanied by his deputy, Droop-a-Long Coyote. In what appeared to be a hillbilly version of Tom and Jerry, Punkin’ Puss was a country bumpkin feline out to catch his nemesis, Mushmouse.

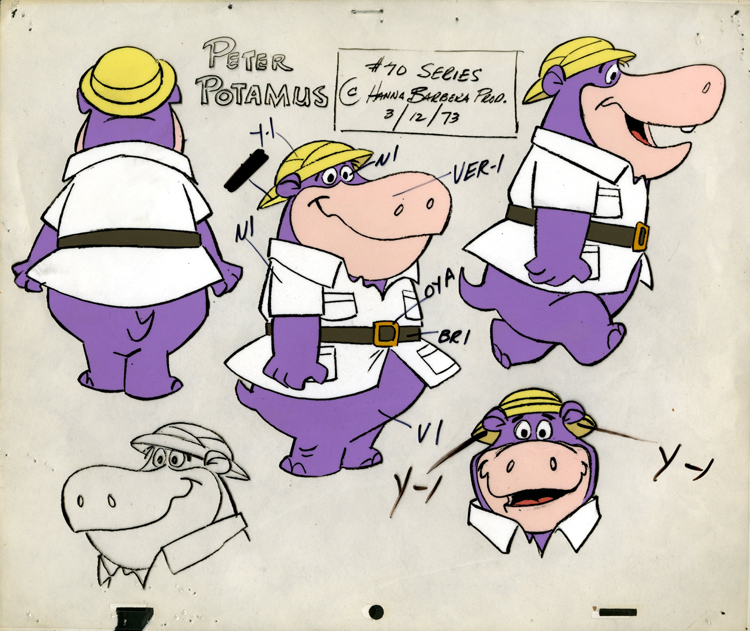

The Peter Potamus Show began running in syndication in the fall of 1964. Jerry Eisenberg, who worked on the show, explained the origins of the character. “Once I was thinking about a hippopotamus… Since I was overweight, I could relate to that. So I started making some drawings in the Hanna-Barbera style—the character standing on two legs. I put a safari coat on him and a pith helmet. Joe kind of liked it, so he got some writers together and we began to work on it. I don’t know who came up with the name, but that was Peter Potamus.” (King, Susan. “Honoring those yabba-dabba-doo-ers, Hanna-Barbera.” Los Angeles Times, 21 August 2009) Additional segments on The Peter Potamus Show included Breezly and Sneezly (a polar bear and seal), and Yippee, Yappee, and Yahooey (three canines in the style of The Three Musketeers).

Fig. 18. Color model cel for Peter Potamus, 1973

In 1964, Hanna-Barbera was tasked with creating the opening and closing credits of the Screen Gems television production, Bewitched. Artist Ed Benedict worked on the animation, which featured protagonist Samantha Stephens riding a broom in full witch garb before twitching her nose and returning home to make dinner for her advertising executive husband, Darren. Those with a keen eye may have noticed that the creators of Bewitched strategically placed some familiar stuffed animals in daughter Tabitha Stephens’ bedroom. Those animals are none other than Hanna-Barbera creations Peter Potamus, Ricochet Rabbit, and Breezly and Sneezly. Additionally, with a wink to his business partners at Hanna-Barbera, during the making of the film version of Bye-Bye Birdie in 1963 director George Sidney made sure to include Fred and Barney dolls in Ann-Margret’s bedroom on set.

Fig. 19. Opening animation still from Bewitched, 1964

Airing in October 1965, The Atom Ant Show and The Secret Squirrel Show became the first series Hanna-Barbera created directly for a Saturday morning network schedule. Assisted in part in 1963 when “[President] Lyndon Johnson endorsed a return to a hands-off FCC, the networks quickly swung back toward their profit-centered practices, encouraging the booming expansion of cartoons on Saturday morning…” (Mittell, p.50) Sponsors were eager to fund a new Saturday morning time slot dedicated just for children, and networks were ready to comply.

The Atom Ant Show featured additional segments Precious Pupp and The Hillbilly Bears. Precious Pupp was a largely forgettable cartoon about a mischievous dog and his elderly owner, while The Hillbilly Bears was an ursine take on the Hatfield/McCoy feud. The Secret Squirrel Show included two new segments, Squiddly Diddly and Winsome Witch, which concerned a squid who lived in a Seaworld-type theme park called Bubbleland, and a globetrotting witch who encountered aliens, fairy tale characters, and even Frankenstein’s monster.

As the superhero genre gained prominence at Hanna-Barbera, these would be the last cartoons in the early “Hanna-Barbera style.” However, “Saturday morning cartoons” had just begun.

1966-1987:

SPIES, SUPERHEROES, AND ADVENTURERS

“…Jonny Quest became one of our most popular shows, and it eventually launched a whole platoon of other Hanna-Barbera cartoon series in the action-adventure genre, including among others The Fantastic Four, Space Ghost, The Herculoids, and The Galaxy Trio.”

–William Hanna, A Cast of Friends, p.145

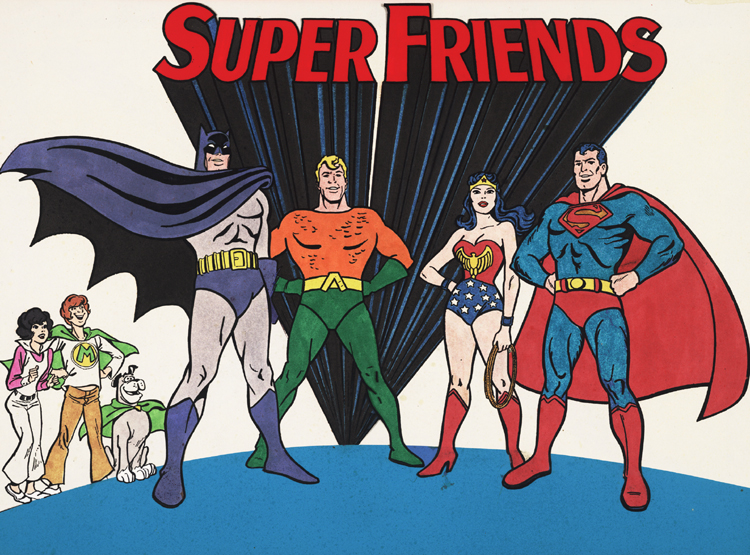

Always with an ear to the ground, William Hanna and Joseph Barbera were cognizant of trends in popular culture. As their audience aged, Hanna and Barbera became aware that many cartoon viewers were becoming interested in the escapades of James Bond on the big screen and the adventures of Spider-Man, The Fantastic Four, and the Justice League in the pages of comic books. They made a decision to begin transforming much of their Saturday morning fare into the action/adventure genre.

Creating more realistic-looking human characters proved to be a challenge for many of the artists used to drawing talking bears and gun-slinging horses. The style needed to look more like comic-book adventures—so who better to draw them than comic book artists? From his hometown in New York, Joe Barbera recruited comic book veteran Doug Wildey to begin drawing cartoons for their changing audience.

In 1986, Wildey talked about the problems faced by Hanna-Barbera’s animators who had spent years drawing anthropomorphic animals:

“These guys were used to drawing cartoon type characters, and they’d come in and they were at a loss. They couldn’t handle adventure stuff. Boy, did I get calls at night! From guys who somehow thought that they were failures simply because they couldn’t handle something like this, which of course was crazy…

But these guys would keep saying, ‘I’m not really that much up on anatomy. I haven’t had anatomy in quite a while. I can’t seem to handle… I mean, the artwork doesn’t look right.’ And I’d look at it and say, ‘Yeah, it sure doesn’t look right. It doesn’t work.’ In the beginning I was the only straight man in the entire organization that could draw a reasonably decent looking human figure.” (Wildey, Doug. “AH Talks to the Brilliant Cartoonist Who Created Jonny Quest.” Olbrich, David W. Amazing Heroes, 15 May 1986: p.44.)

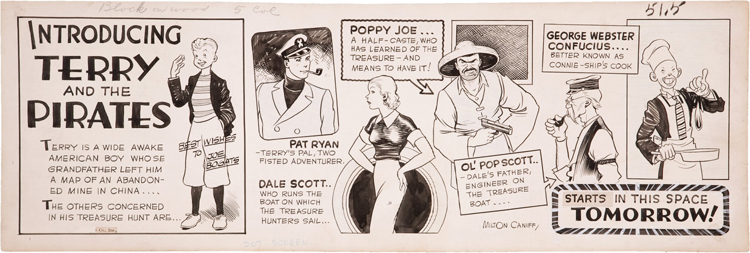

The first creation for this stylistic change was Jonny Quest. Barbera’s fascination with Milt Caniff’s 1930s comic strip Terry and the Pirates influenced the composition of the new series, as did the radio serial Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy. Wildey noted, “We started to think about names and got serious. So, I thought, where do you get names? The L.A. phone book. Went through the L.A. phone book and finally Quest hit me. ‘Quest’ has an adventure sound to it…. And Joe contributed Jonny without the “h.” (Wildey, p.40)

Fig. 20. Milton Caniff, Terry and the Pirates daily comic strip drawing, 1934

Jonny Quest was created to be an all-American 11-year-old boy who accompanies his father, Dr. Benton Quest, on adventures around the world. They were joined by Jonny’s caretaker, Race Bannon, Jonny’s adopted brother, Hadji, and their pet dog, Bandit. Throughout their trips around the globe they encountered such villains as treasure hunters, pirates, and a robot spider, in addition to their nemesis Dr. Zin, who appeared in multiple episodes. Young actor Tim Matheson provided the voice of Jonny Quest and would continue doing voices for Hanna-Barbera cartoons Sinbad, Jr., Space Ghost, and Samson and Goliath over the next few years.

Fig. 21. Doug Wildey, Presentation board for Jonny Quest, ca.1964

The first season of Jonny Quest proved to be very popular. Airing in prime time, the show’s unique style, superb musical composition by Hanna-Barbera veteran Hoyt Curtin, and inclusion of futuristic technological innovations entranced viewers young and old. However, due to a schedule change and high production costs, the show was cancelled after only one season. During the 1964 season, The Flintstones began suffering a loss of viewers who were tuning in to the new series The Munsters. Rather than risk cancellation of their groundbreaking stone-age cartoon, after just a few months on air Hanna-Barbera decided to move Jonny Quest from its Thursday airing to the Friday time slot of The Flintstones. The Flintstones would now be opposite Rawhide on Thursday, which was not a challenge to its audience and would allow for two more years of The Flintstones. Although it was cancelled after the end of that season, repeats of Jonny Quest would continue to be aired on Saturday mornings for several years, albeit in a slightly altered form. However, the massive popularity of Jonny Quest meant more exciting adventures were yet to come.

The Atom Ant Show and The Secret Squirrel Show joined NBC’s Saturday morning schedule for the 1965 season. Atom Ant, though he was a mere arthropod, was able to fight bad guys with his super strength and ability to fly while shouting his catchphrase, “Up and at ‘em, Atom Ant!” Secret Squirrel capitalized on the Cold War spy craze of the early 1960s. Secret Squirrel, also known as Agent 000 of the International Sneaky Service, was joined by the fez-wearing Morocco Mole who aided Secret Squirrel in battling enemy agents. Veteran voice artist Mel Blanc provided the voice of Secret Squirrel for the series.

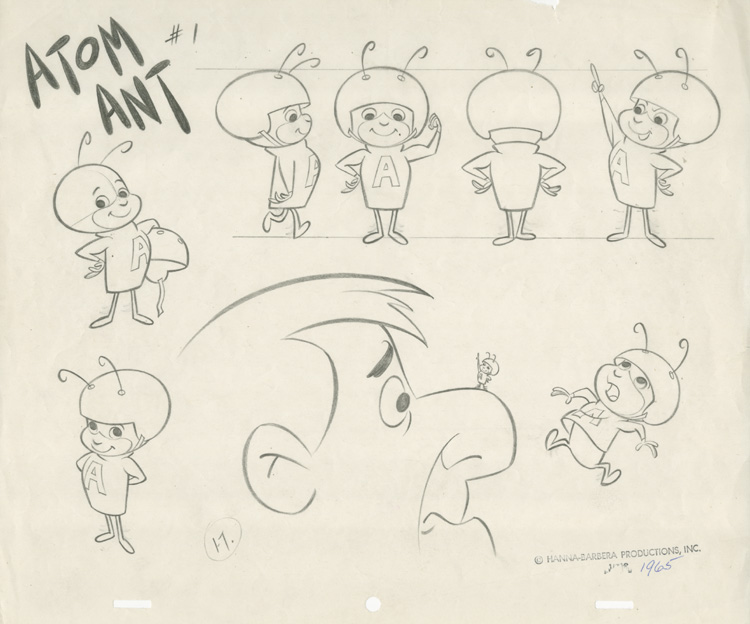

Fig. 22. Model sheet for Atom Ant, 1965

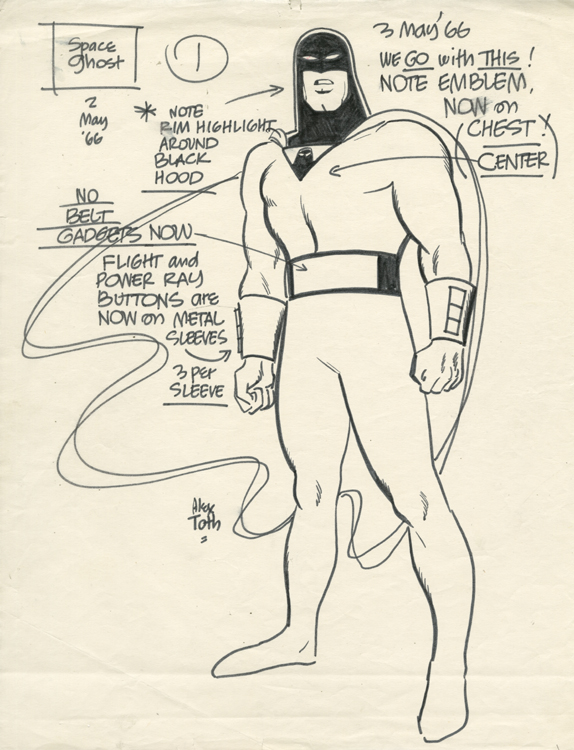

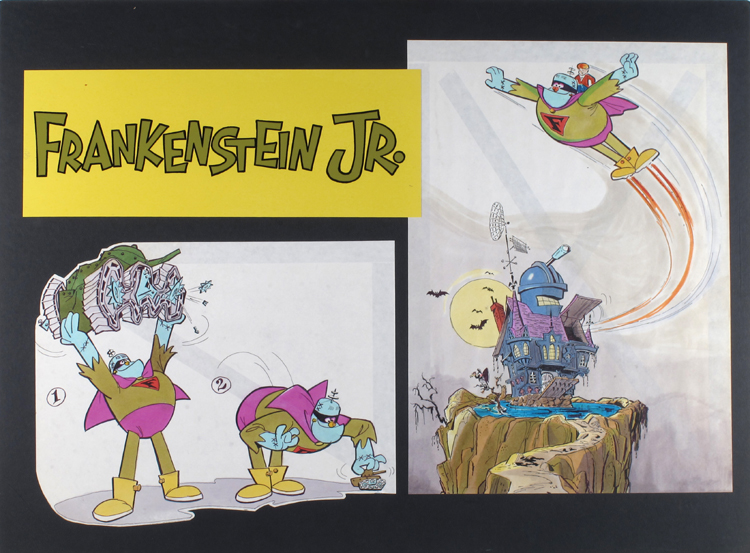

In 1966 Fred Silverman, head of daytime programming for CBS, met with Hanna and Barbera to discuss revamping his network’s Saturday morning schedule into a “superhero morning.” (Barbera, 166) In addition to Wildey, Barbera had hired comic book artists Alex Toth, Mel Keefer, and Warren Tufts to assist with creating, designing, and animating new action-oriented series. In the late 1940s, Toth began work as an artist for DC comics, drawing popular titles like Green Lantern, All Star Comics, and Flash Comics. His initial focus at Hanna-Barbera was the development of Space Ghost, which followed the adventures of an interplanetary crime fighter and his teen sidekicks, Jan and Jace, and their pet monkey, Blip. The new series Space Ghost and Dino Boy was paired with Frankenstein Jr. and the Impossibles for the 1966 CBS Saturday morning schedule. Once the Neilsen ratings were in, Silverman knew he had struck gold. Space Ghost and Dino Boy was enormously popular, receiving a 55 share in the Neilsen ratings. (Barbera, 167) The Space Kidettes, featuring a team of child space adventurers, debuted on NBC that same year.

Fig. 23. Alex Toth, Model sheet for Space Ghost, 1966

The 1967 schedule included additional superhero series created by Hanna-Barbera, such as Birdman and the Galaxy Trio, Shazzan!, Moby Dick and The Mighty Mightor, Samson and Goliath, The Fantastic Four, and The Herculoids, which received an astounding 60 share in the ratings. (Barbera, 168) Six of the ten Saturday morning slots on CBS that season were filled by superhero series from Hanna-Barbera.

Though the action/adventure cartoons were well received by audiences, some people were concerned about the detrimental effects of cartoon violence on children. Just as Dr. Fredric Wertham’s 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent, which claimed that juvenile crime and societal discord were caused by the content of comic books, had a negative impact on that industry in the mid-1950s, so was a new generation setting out to sanitize popular culture, for many of the same reasons.

The progressive group Action for Children’s Television (ACT) was organized in 1968 by Peggy Charren, niece of screenwriter Sidney Buchman, who was blacklisted in the 1950s for being a communist, though he went on to write the screenplay for Elizabeth Taylor’s 1963 film, Cleopatra. ACT was responding to what they perceived to be too much commercialism and violence in children’s television. Their first target of intimidation was the children’s television show, Romper Room. They next set their sights on Saturday morning action/adventure cartoons like Space Ghost, Frankenstein Jr., and The Herculoids.

Fig. 24. Presentation board for Frankenstein Jr., ca.1966

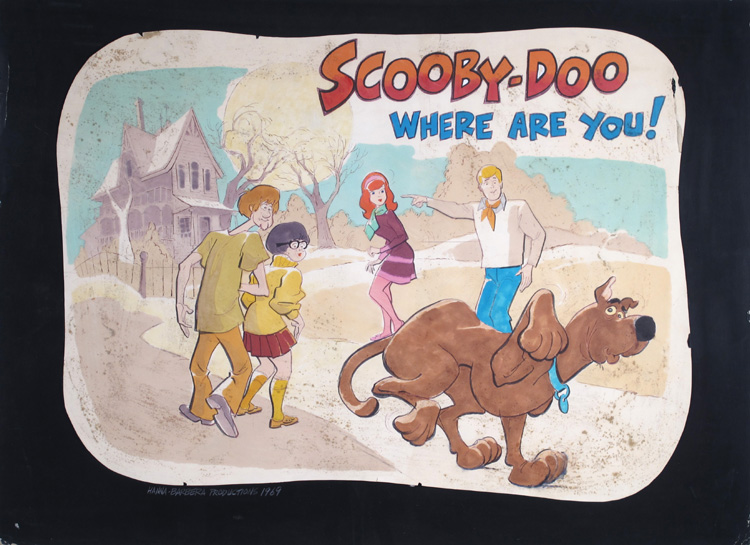

Public pressure soon led to the demise of this genre, and all of the Hanna-Barbera action/adventure series were off the air by September 1969. In their place, fluffier fare was introduced, such as Hanna-Barbera’s The Banana Splits Adventure Hour, Wacky Races, the comedy/mystery series Scooby-Doo, Where Are You!, and Sid and Marty Krofft’s H.R. Pufnstuf.

Further targets of ACT included manufacturers of children’s vitamins, who had been longtime sponsors of children’s cartoons. Earlier Hanna-Barbera creations like Tom and Jerry and Jonny Quest would be forced to edit out violence in order to be permitted to be broadcast in the 1970s and later. In 1995, following a court decision upholding government regulations, Charren admitted, “Too often, we try to protect children by doing in free speech.” (Andrews, Edmund L. “Court Upholds a Ban on ‘Indecent’ Broadcast Programming.” The New York Times, 1 July 1995.)

THOSE MEDDLING KIDS...

Always seeking new and exciting programming, in 1968 CBS executive Fred Silverman got the idea to develop a new Saturday morning cartoon in the vein of the radio drama series “I Love a Mystery.” That detective series aired on NBC radio from 1939 to 1942 and CBS radio from 1943 to 1944 and featured three male detectives who traveled the world together in search of mystery— both man-made and supernatural. The team’s motto, “No job too tough, no adventure too baffling,” and episode titles like The Monster in the Mansion, no doubt provided inspiration for Silverman’s quest.

A fan of animation, Silverman worked closely with Hanna and Barbera to develop his idea. The characters who would become Fred and Shaggy were influenced by Dwayne Hickman’s Dobie Gillis and Bob Denver’s Maynard G. Krebs, characters from the early 1960s CBS series The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis. The recent ABC series, The Mod Squad, which featured a multi-cultural group of hip young detectives, informed the cartoon’s overall look and design. Geoff Jones, Mike Andrews, Kelly Summers, Linda Blake, W.W., and their dog, Too Much, formed the group in Mystery’s Five.

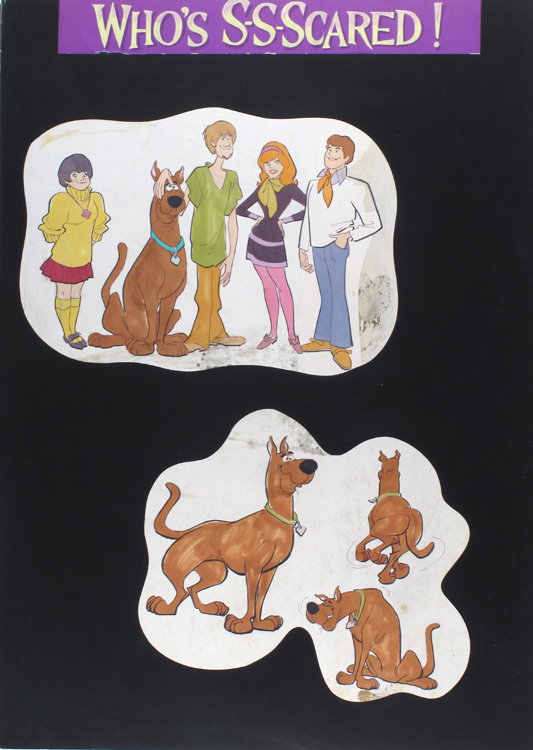

Fig. 25. Presentation board for Who’s S-s-scared!, 1969

With CBS executives wary of the recent outcry against violence on television, they proposed that Hanna-Barbera include some comic relief to lighten the tone of the cartoon. According to Hanna-Barbera’s layout and character designer Bob Singer, Barbera suggested that laughs could be provided by the canine, since Jonny Quest’s pet dog, Bandit, was so popular in the earlier series. Silverman loved the idea so much he decided that the dog should be the star of the show and Barbera assigned Hanna-Barbera veteran Iwao Takamoto to design the animal. The re-designed series featured the final line-up of Fred, Daphne, Velma, Shaggy, and Scooby-Doo and was christened Who’s S-s-scared! Once again, the network worried that the title might prove too frightening for its target audience. However, once Scooby-Doo’s personality and role within the group were broadened, the network approved the purchase of the re-titled series, Scooby-Doo, Where Are You!

Fig. 26. Iwao Takamoto, Presentation board for Scooby-Doo, Where Are You!, 1969

There is an oft-quoted story of Fred Silverman having an epiphany while flying to a meeting. When listening to music on the airplane’s headset, Silverman heard Frank Sinatra sing the standard Strangers in the Night. Sinatra’s final line of “doobydooby-doo” gave Silverman the idea to name the dog Scooby-Doo and the rest is history. However, Iwao Takamoto notes in his autobiography that “somewhere in the archives, dating back to the early 1960s, there is a development drawing of a dog character with the name ‘Scooby’ attached to it. It’s nothing like our Scooby-Doo, but it is there. I’ve seen it.” (Takamoto, p.125) During my research for this exhibition, I located the artwork Takamoto mentioned. His memory served him well, although in the earlier piece the dog’s name was spelled “Skooby.” Whatever his origin, Scooby-Doo was soon to become one of Hanna-Barbera’s major successes.

In its original series, the gang encountered all sorts of spooky adversaries such as The Creeper and a Swamp Witch, though the villain invariably turned out to be a greedy or disgruntled caretaker or carnival worker they had encountered earlier in the story. As Joe Ruby and Ken Spears’s original treatment notes, “A logical ending always caps our stories, as the Mystery’s Five solve the most baffling tales of the unknown ever told!!”—meaning the bad guys could always be explained.

Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! enjoyed a very successful run for two seasons, returned with celebrity guest stars for a third season, was featured on a new series, Laff-A-Lympics, and was joined by Scooby’s nephew, Scrappy-Doo. The Richie-Rich/Scooby-Doo Show, debuting in November 1980, was the only time Scooby received second billing. Scooby-Doo remains one of Hanna-Barbera’s most successful creations. Except for a two-year hiatus in the 1980s, a Scooby-Doo series aired on Saturday morning television every year from 1969 to 1991.

Fig. 27. Presentation board for Josie and the Pussycats, ca.1970

The enormous success of Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! inspired Hanna and Barbera to recycle the idea of mystery-solving meddling kids. Often using a dog or a similar character device as a comedic sidekick to offset frightening qualities, Hanna-Barbera applied Scooby-Doo’s formula again over the next several years in such animated series as Clue Club, The Funky Phantom, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kids, Speed Buggy, Jabberjaw, Captain Caveman, Josie and the Pussycats (the first cartoon with a black female lead), Goober and the Ghost Chasers, The Buford Files, The New Shmoo, and The Amazing Chan and the Chan Clan.

HANNA-BARBERA CONQUERS SATURDAY MORNINGS

In 1965, with their animation studio more successful than ever, Hanna and Barbera made a difficult decision: to sell the studio they had founded together nearly a decade before to eager buyer Taft Broadcasting. However, the sale was delayed for several months after Harry Cohn’s family filed a lawsuit regarding the sale a few years earlier of his private stock in the company.

Animator Jerry Eisenberg explained, “The sale was supposed to go through [in 1965], but a lawsuit came about where the widow of Harry Cohn, who was the head of Columbia Studios, there was Hanna-Barbera private stock that was issued. He had stock, Joe and Bill did, and I guess George Sidney who was their silent partner. Anyway, at some point, after Harry Cohn passed away, Bill Hanna and his people, they approached Mrs. Cohn offering to buy her shares. And I guess Bill Hanna’s people said the stock is worth so much, so she sold them whatever she had. But then when the sale was announced, it was in the trade papers and stuff, that the company was being sold [for $12 million], Mrs. Cohn’s attorneys figured out… they felt that Bill Hanna and his people undervalued the stock at that time. So they filed suit and that held up the sale about a year.” (Shostak, Stu. “Stu’s Show.” Audio blog post. Program 221: A Look Back at the Early Days of the Hanna-Barbera Cartoon Studio. Stu’s Show, 16 March 2011. Web.)

With the sale of Hanna-Barbera complete the following year, the late 1960s marked a turning point in the look of Hanna-Barbera’s animation. Just as the “Hanna-Barbera style” had changed when the company hired comic book artists to illustrate for the new action/adventure genre cartoons, the style would again evolve as cartoon veterans who had built Hanna-Barbera into an animation powerhouse began retiring and new artists and writers were hired. Furthermore, the amount of material the studio produced would continue to expand, often pushing the bounds of what Hanna-Barbera could accomplish.

Men who had spent decades refining and perfecting the comedy animation of Betty Boop, Popeye, Bugs Bunny, and nearly all the pre-1960s iconic cartoon characters—Michael Maltese, Dan Gordon, Warren Foster, and Tony Benedict—who helped make Hanna-Barbera a successful studio would soon be replaced by younger staff without the same level of experience, and by international animation teams with even less experience. Michael Maltese, arguably the greatest cartoon writer of all time, joined Hanna-Barbera in 1958 after working at Fleischer Studios, Schlesinger, and Warner Bros. from 1937 to 1953 and from 1955 to 1958, where he created such iconic cartoons as Duck Dodgers in the 24-1/2th Century (1953), Duck Amuck (1953), One Froggy Evening (1955), and What’s Opera, Doc? (1957). Director Steven Spielberg referred to One Froggy Evening as “the Citizen Kane of the animated short.” (Spielberg, Steven. “Chuck Jones: Extremes and In-Betweens—A Life in Animation.” Great Performances, November 21, 2000.) Furthermore, in animation historian Jerry Beck’s 1994 book, The 50 Greatest Cartoons: As Selected by 1,000 Animation Professionals, those cartoons were chosen, respectively, as the #4, #2, #5, and #1 cartoons of all time. (Beck, pp.45, 37, 49, 30)

At Hanna-Barbera, Maltese was responsible for many scripts for The Flintstones, The Jetsons, and The Yogi Bear Show, as well as Quick Draw McGraw, for which he wrote every episode. Robert J. McKinnon wrote in his book, Stepping into the Picture: Cartoon Designer Maurice Noble, “For the [Chuck] Jones unit [at Warner Bros.], the departure of Michael Maltese was a particularly striking blow as his contributions had been integral to the team’s success for so many years. In late 1958, Maltese was hired by the Hanna-Barbera studio to write for their new limited animation television cartoons featuring characters like Yogi Bear, Huckleberry Hound and The Flintstones, all of which became highly successful. [Artist Maurice] Noble recalled his arrival back at Warner Bros. after his second stint at Sutherland: ‘I went into the studio and looked in Mike’s room, and found he was gone. When I asked Chuck about it, he told me Mike had left the studio, along with some others [such as writer Warren Foster]. There was no big farewell or anything like that. It was kind of sad.’” (McKinnon, p.148) Maltese retired from Hanna-Barbera in 1970.

Warren Foster began working for Fleischer Studios in 1930 where he wrote scripts for that decade’s biggest star, Popeye. He then moved to Warner Bros. where he worked from 1938 to 1957, writing stories for 117 shorts. In Michael Barrier’s book, Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in its Golden Age, Warner Bros. animator Bob Clampett recalled that Foster was “the guy who would know all of the gags on a certain subject that had ever been used anywhere.” (Barrier, p.478) Foster joined Hanna-Barbera in 1959 and began writing scripts for several series, including The Huckleberry Hound Show, The Yogi Bear Show, and The Flintstones. Regarding Foster, Hanna-Barbera animator Iwao Takamoto noted, “I believe his influence was one of the key factors for [The Flintstones] success.” (Takamoto, p.96) Foster left Hanna-Barbera in 1966.

Dan Gordon began working at Van Beuren Studios in the 1930s before moving to Terrytoons, where he met Joseph Barbera. He then went to work for Fleischer Studios, which was later renamed Famous Studios, on their Popeye and Superman shorts. After focusing on comic book work in the 1940s, Gordon joined Hanna-Barbera during the earliest days of the studio to help write for such series as The Ruff and Reddy Show, The Huckleberry Hound Show, and The Yogi Bear Show, as well as The Flintstones, for which he and Joseph Barbera created the first episodes. Gordon worked for Hanna-Barbera until his death in 1970.

The youngest of Hanna-Barbera’s writers in the early years, Tony Benedict, started in the animation industry as an in-betweener on Walt Disney’s Sleeping Beauty in 1956. He then joined UPA in 1959 where he worked as assistant animator and storyboard artist for their hit Mister Magoo. Benedict began at Hanna-Barbera as a writer on the Yakky Doodle segment of The Yogi Bear Show in 1961, and quickly moved on to write for several series, including The Magilla Gorilla Show, The Peter Potamus Show, The Flintstones, Top Cat, Ricochet Rabbit, and The Jetsons, for which he wrote the script which introduced the family’s pet dog, Astro. Benedict fondly remembered his working relationship with Barbera: “Joe was the only person I had to please. All [Joe] asked was ‘Is it funny?’ No one else approved my stories.’” (Benedict, Tony. Personal interview. 22 April 2016.) Benedict left Hanna-Barbera in 1967 after the company was sold to Taft Broadcasting. He went on to write and direct the independent animated feature Santa and the Three Bears (1970) and continued to animate for various studios until his retirement.

During this period of change at Hanna-Barbera, the studio was facing an increased demand for new material. However, the demand was more than the studio could handle at its home base in Los Angeles, and they were forced to seek additional help outside of the United States. Hanna noted, “Our facilities had become extended to the bursting point. We literally had every available qualified animator in town busily engaged in some production or another.” (Hanna, p.193) According to animator Jerry Eisenberg, “[In 1969] we were averaging 1,200 feet of animation per week. All of a sudden, it went to 5,000 or so. So that’s what caused Bill Hanna to have to go out of the country looking for help. There weren’t enough people here. That’s when he started with Japan and, of course, it went to Korea and the Philippines, and places like that, Australia.” (“Jerry Eisenberg, Part Five, Bobe, Spence, and Lew’s Deal.” YOWP, March 16, 2011, yowpyowp.blogspot.com) In 1971, The Funky Phantom, a cartoon about a group of teens who solve mysteries with the help of a ghost from the Revolutionary War and his cat, became the first Hanna-Barbera cartoon to be created completely outside of the United States. (Takamoto, p.137)

The use of Xerography was also becoming commonplace in the television animation industry. Used by Walt Disney extensively for 101 Dalmatians, the process of Xerography eliminated the step of having someone trace and paint the lines on the cels from the animator’s drawings. With Xerography, someone could simply feed the animator’s drawings through the Xerox machine and then paint directly onto the copied cels. While there was a substantial savings in time and money, the look of the cartoon lost the heavy lines of the early 1960s examples and the overall value of the animation suffered. Writer Tony Benedict recalled, “It degraded the quality. It was not a nice, clean line… There was some high skill in that inking and painting [department before Xerography], it wasn’t just like a coloring book. You had to be extremely accurate.” (Benedict, Tony. Personal interview. 22 April 2016.)

A major change to the look and feel of Hanna-Barbera cartoons during this period would come from the outside. Due to pressure from the group Action for Children’s Television (ACT) in the late 1960s, the studio was forced to address complaints of violence in its cartoons. This meant a change in overall tone to lighter fare for the Hanna-Barbera style. One misfire was the cartoon Yogi’s Gang, which debuted in 1973. In order to appease ACT while also providing educational content, the pendulum swung too far in the other direction. Instead of being entertaining, the series was perceived as overly preachy and lacking the fun elements of previous series. Yogi’s Gang contained unfortunate plots, which included Yogi and other Hanna-Barbera characters encountering polluters like Lotta Litter and Mr. Smog, and confronting villains with bad intentions such as The Sheik of Selfishness, The Envy Brothers, and Mr. Sloppy. The series lasted only seventeen episodes.

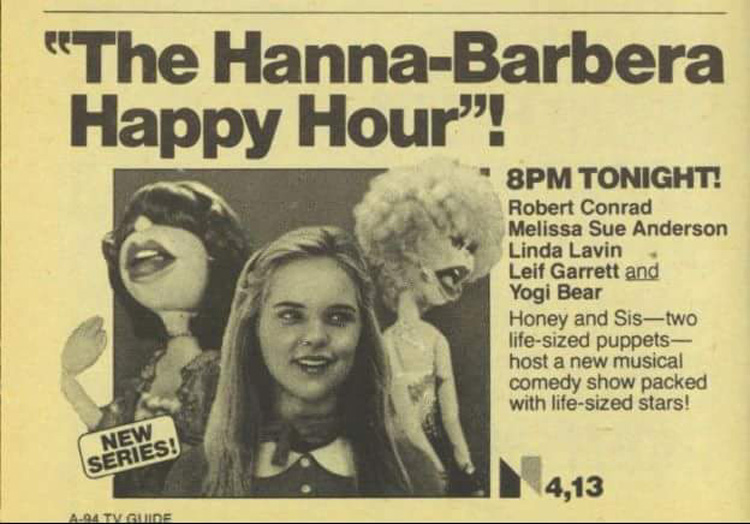

One successful example of fluffier fare included Hanna-Barbera’s first series to combine live-action segments with cartoons. In a throwback to TV cartoon presentations from the 1950s, Hanna-Barbera began developing a program of animated shorts introduced by hosts, in this case humans in animal suits, designed by Sid and Marty Krofft. Before the hosting team of Fleegle, Drooper, Bingo, and Snorky were named The Banana Splits, the series had gone through several name changes, including Kellogg’s Korny Kritters, Kellogg’s Presents the Hanna-Barbera Happy Hour Starring the What Furr’s, and The Banana Bunch.

Fig. 28. Presentation board for Kellogg’s Presents the Hanna-Barbera Happy Hour Starring the What Furr’s, ca.1968

In a 1993 interview with Film Threat magazine, Sid Krofft noted, “[We] were the only ones—including Disney—putting people inside of suits at the time. No one had ever heard of that. So we took the order and built the suits. When [the characters] walked out of the building, I look at my brother and said, ‘They’re going to make millions.’” According to Hal Erickson’s book, Sid and Marty Krofft: A Critical Study of Saturday Morning Children’s Television, 1969–1993, “the brothers have always credited the series’ [The Banana Splits] success as the door-opener for their own entrée into weekly television,” including such hits as H.R. Pufnstuf, Lidsville, Sigmund and the Sea Monsters, and Land of the Lost. (Erickson, p.15) The Banana Splits Adventure Hour, sponsored by Kellogg’s, debuted on NBC on September 7, 1968, and featured the cartoons Arabian Knights and The Three Musketeers, as well as the live-action serial Danger Island, directed by Richard Donner, who would go on to direct such hit films as Superman: The Movie (1978), The Goonies (1985), and the Lethal Weapon franchise (1987–1998).

Fig. 29. Promotional photograph for The Banana Splits Adventure Hour, 1968