For many Chinese creators, Chinese traditional culture and art are the foundation of their artistic influences, and this heritage cannot be ignored. Due to vast changes and transitions of Chinese society and culture, artists had the experience of struggling between the tradition of Chinese art and the shock of modern influences. Since the 19th century, culture and art coming from the Western world have been a great influence on Chinese society. From then on, numerous artists began to use solely the techniques and concepts from the Western art system and ignored the heritage of Chinese traditions at all. However, there are still people who find the balance between West and East, and between new influences and tradition. In the history of Chinese modern art, many illustrators were able to find a way to absorb features of Chinese traditional art and use it to help them form their own creative system. Some of these illustrators were deeply influenced, noticeable in the visible Chinese flavors in their work that shine through their own distinct styles. Some of them did not inherit any traditional technique deliberately until they found it was already an important part of their creative practice.

This essay will focus on three Chinese illustrators active from the 1920s to today, to analyze their work from different aspects and show how they applied Chinese traditional art spirits and techniques in their illustrations. The illustrators are Zikai Feng, who was active since the 1920s and known as the father of the comics in China; Gao Cai, a master of incorporating folk art in her work who has been active since the 1980s; and Liang Xiong, who explored the possibilities of Chinese techniques in modern picture books from 1990s till now. These three illustrators are from different times and experienced diverse changes in Chinese society and the art market. Each of them managed to find his or her own ways to absorb nutrients from Chinese traditional art, and successfully brought them in front of the public together with their distinct art styles.

Zikai Feng: Pioneer

Zikai Feng (Simplified Chinese:丰子恺) (1898-1975) was an important Chinese artist, illustrator, writer, translator, and educator in the 20th century. He started his career as a comic artist and illustrator in the 1920s and was generally considered the first pioneer of Chinese comic art.

Like many artists of the time, Feng started his art practice by learning art techniques from the Western world. He went to Japan, which was the most convenient and popular country for Chinese people to receive Western art education.[1] In Japanese art school, Feng learned the basic techniques of graphite drawing and oil painting. What influenced him the most, however, were not his experiences in school, but the comic booklets of a Japanese artist, Takehisa Yumeji (1884-1934). Through Yumeji’s simple ink drawings, Feng realized for the first time that artists could find a distinct style with traditional Eastern techniques and that the Western art system should not be the only presence in modern art.[2]

Fig. 1. Takehisa Yumeji, A Late Arrival at Home (title translated by the author), n.d.

From then on, Feng started his exploration to apply ink drawing with brushes in a new way. At first, he simply imitated Takehisa Yumeji’s works. However, he began to build a system of his own, and created an original art style that quickly became popular in China. In his work, traditional Chinese techniques start to meet with modern art forms such as comics (fig. 2). He actually created a new art genre that was between narrative comics and illustration in literature, which was unprecedented in China. One of the editors and art directors he worked with, Zhenduo Zheng (郑振铎), coined the name of the genre, Manhua (漫画). Soon, Manhua started to be popular and eventually fused with the concept of comics in China.

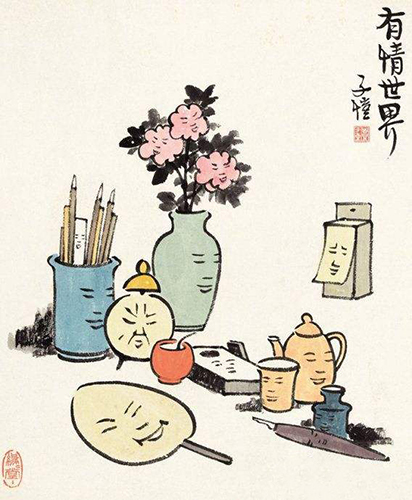

Fig. 2. Zikai Feng, A World of Sentient Beings (title translated by the author), n.d.

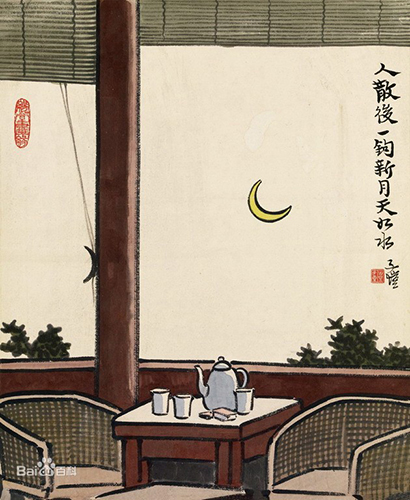

In one of his most famous early works (fig. 3), he depicted a space that does not present any figures in it but only chairs, a tea table, a window, and a moon in the sky. The title of the picture, which can be roughly translated in English as After people had left, a New Moon and the Water-like Sky, implied the narration behind it. It was focused on the moon and night sky from the view of a window in a room after people had left. The illustration offers a peaceful scene of ordinary daily life. The appreciation of this daily life is an important part of Feng’s artistic vision. He drew in a simple and artless, yet not insipid, way.

Fig. 3. Zikai Feng, 人散后,一钩新月天如水, 1920s.

In this work, except for the simplified and abstract approach of depicting objects, there is another important method he used in the sky that can be identified as Chinese. We can understand from the title of the work that the most important feeling Feng wanted to give people was the sense of emptiness and tranquility. To achieve this goal, instead of painting a dark background, Zikai Feng left an empty space for the night sky, where we can only see a new moon hanging on the paper-white area. This is a typical Chinese way to manage vast and rather empty space, such as sky or water. Traditional Chinese artists tend to leave those spaces empty so that audiences can feel the fluidity and rhythm of the composition. As we can see in A Night on A Mountain of Pine Trees by an unknown artist from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) China, the painter chose to leave the background empty to create a transparent and quiet night sky (fig. 4). By applying the same technique, Feng created a light and simplified space that was crucial for the atmosphere he wanted to convey.

Fig. 4. Unknown artist, A Night on A Mountain of Pine Trees (title translated by the author), Song Dynasty (960-1279).

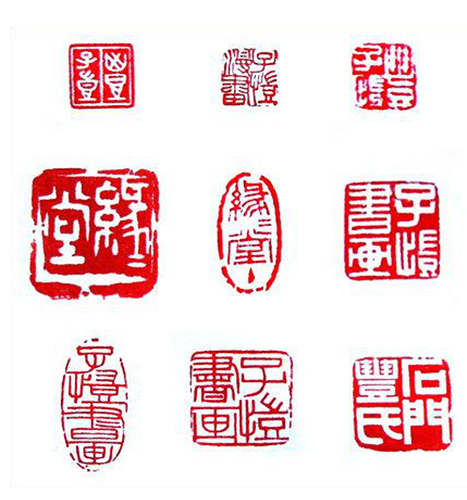

Moreover, the artist naturally applied stamps (fig. 5) and calligraphy, as well as poetry in his comics and illustrations. The combination of the elements with painting has always been a distinct feature of traditional Chinese art. Feng incorporated that in a new art genre very well.

Fig. 5. Zikai Feng, Various stamps, n.d.

Gao Cai: A Poetic World of Folk Art

Gao Cai born in 1946 in Changsha city, China, is a successful illustrator who focuses on children’s picture books. She worked as a book editor before devoting her life to telling illustrated stories for children. She started her art practice in the 1980s when the picture book was a completely unfamiliar concept to the Chinese public. She created many books based on Chinese traditional folk stories, nursery rhymes, and literature. Her most famous works include The Story of Taohuayuan (Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2009), June the Sixth (Zhejiang Juvenile and Children’s Publishing House, 2010), and The Fox Fairy in the Wilderness (Publication information and year unknown). Her picture books were published in China, Japan, and Korea and were widely welcomed by children from different cultures.[3]

In her work, Cai inherited the philosophy of life from many poets, artists, and philosophers in Chinese history. In her idyllic images, people could see an ideal lifestyle from Chinese tradition. The values Cai conveys from her works appeal to many modern audiences both in China and overseas. Her works were published in many countries and she has won multiple international awards, such as the Golden Apples in Biennial of Illustrations Bratislava in 1993.[4]

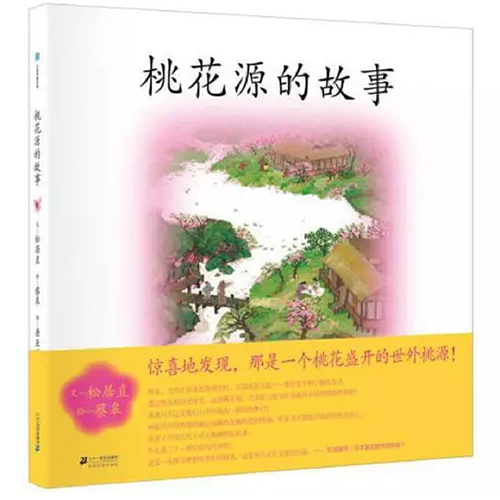

Fig. 6. Gao Cai, Book cover for The Story of Taohuayuan (Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2009). (Title translated by the author.)

Her most well-known book, The Story of Taohuayuan (Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2009) (fig. 6), was based on a famous story in Chinese literature history, which is called The Peach Blossom Land (桃花源记).[5] The original text written in 421 C.E. by Chinese famous poet and writer Tao Yuanming (陶渊明) shows people an imaginative utopia that is independent and separated from the outside world, and where a small number of people lived happy and peacefully together.[6] The story offers Chinese audiences across thousands of years a vision of an ideal life. In order to create an atmosphere that suits the philosophy behind the story in the most efficient way, Cai applied techniques of Chinese traditional landscape painting. She used a river in her composition to run through the whole story. But instead of fully painting it she decided to leave the space empty and white. By doing this Cai allows audiences to see a consistent open space on every page. She also used different brush skills to elaborate on features of the environment, such as the humidity of the air, level of sunshine, and the layers of vegetation. Using multiple techniques, all of the elements she illustrated form a picture that is mysterious and dreamlike, yet sweet and peaceful. In general, Cai often elaborated on the natural environment with the help of multiple traditional techniques. By doing this, the artist successfully gives people a sense of the importance of natural elements in Chinese art and literature.

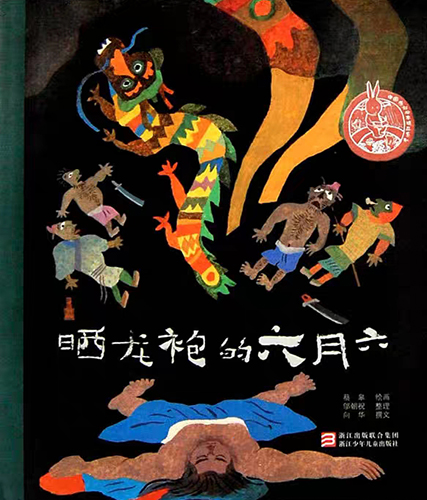

Fig. 7. Gao Cai, Book cover for June 6th (Changsha: Hunan Juvenile and Children's Publishing House, 2008). (Title translated by the author.)

Apart from techniques of traditional landscape painting, another charming feature that Cai’s art presents is the style of Chinese folk art. One can distinguish features of shadow plays depicted on the architecture that is represented in her work, techniques of new year prints on the children characters she created, and paper cutting textures in her decorative details. In one of the illustrations in her picture book Ganjiang and Moye (干将莫邪, Hunan Juvenile and Children’s Publishing House, 2016), created based on a swordsmith couple’s story from the Spring and Autumn period of Chinese history, the illustrator designed the composition with the characters and architecture following the visual format of the traditional Chinese shadow play, “an ancient form of storytelling and entertainment which uses flat articulated cut-out figures (shadow puppets) which are held between a source of light and a translucent screen or scrim.”[7] Cai also took advantage of the art of folk crafts in western-southern China. For example, her book June 6th (Changsha: Hunan Juvenile and Children's Publishing House, 2008)[8] was about a traditional festival in Tujia culture (an ethnic minority in the People’s Republic of China that mainly live in Hunan, Hubei, and Guizhou Provinces). Cai incorporated the aesthetics from the Tujia people’s embroidery crafts and textile design into her illustrations (fig. 7), which we can identify from the color palette and ornamental elements she used on characters’ clothing. The innovative artist incorporated multiple techniques freely and skillfully, and formed a distinctive style naturally.

Liang Xiong: Innovation in Picture Books

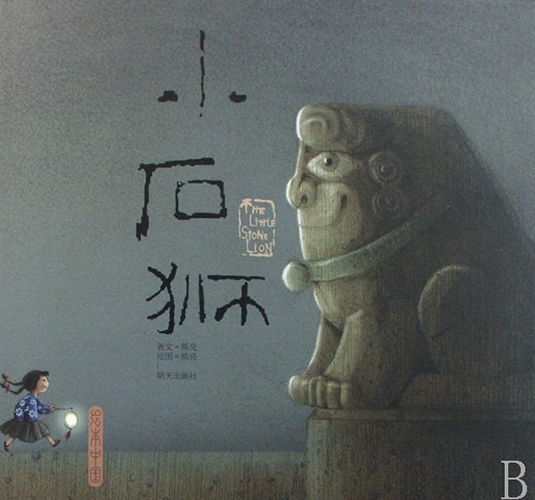

Similar to his early predecessor, Zikai Feng’s experience, Liang Xiong (born in 1975) started his practice following Western cultural tradition and techniques. His first picture book, created in the 1990s, was a adaptation of Franz Kafka’s 1915 novel, The Metamorphosis. At that time, Chinese audiences tended to appreciate Western modern art better than Chinese traditional styles. But Xiong presciently realized that there will be a demand for works that stand for Chinese aesthetic values. Through the years, he created a number of books based on Chinese folk stories and applied traditional techniques in his works. He started his exploration by incorporating cultural elements. For example, in one of his early works, The Little Stone Lion (Jinan: Tomorrow Publishing House, 2007) (fig. 8), he used a stone lion, which is a common ornament of traditional Chinese architecture, as the main character of the story.[9]

Fig. 8. Liang Xiong, Book cover for The Little Stone Lion (Jinan: Tomorrow Publishing House, 2007). (Title translated by the author.)

Soon, he started to use ink painting with a rather traditional color palette, and incorporated augmentation with a digital program in most of his works. He created his own style that has a strong visual identity by using brush strokes and textures in a traditional way that was seldom used in children’s illustrations at that time. It took several years for him to find opportunities for publishing. Yet his works proved to be successful in the Chinese children’s book market afterward. He received several opportunities for publishing his works and introducing them to people outside of China. In 2018, he managed to be the first Chinese illustrator who was on the shortlist for the Hans Christian Andersen Awards.[10]

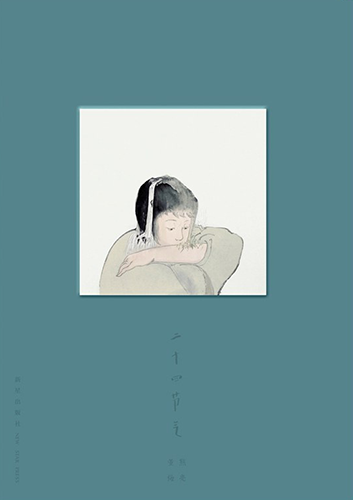

Fig. 9. Liang Xiong, Book cover for The 24 Solar Terms (Beijing: New Star Press, 2015). (Title translated by the author.)

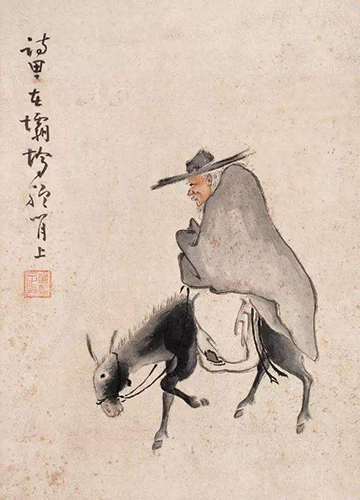

In one of his most famous works, The 24 Solar Terms (fig. 9), Xiong designed several characters that stand for different solar terms.[11] The twenty-four solar terms are Chinese concepts for seasons and periods of a year. In fact, Ancient Chinese people divided a year into twenty-four periods and gave them poetic names to represent the natural features of that period. The concept of the terms was also used as an instruction for agriculture. Xiong used brushes and ink to depict the figures and give them a very organic feeling. The unique texture language produced by brushes is typically Chinese and suits the nature-related topic very well. Mottled spot-ink and iterative-wrinkles are important skills in Chinese painting which are used in both landscapes and human figures (fig. 10). Xiong incorporated them skillfully in the narrative system of the picture book.

Fig. 10. Shen Huang (黄慎) (1687-1772), Pondering over a Poem on Donkey, n.d. (Title translated by the author.)

Conclusion

Since the 19th century, Chinese art and culture encountered tremendous shock by being exposed to art and culture from the Western world. From then on, Chinese artists in all genres had to face the choice of inheriting the tradition or adapting to a completely new world. Many of them found the way in between. They explored the possibility of balancing traditional skills and modern forms. Illustrators from different generations brought the charm and beauty of traditional art in front of modern audiences both in China and overseas. The three illustrators presented in this essay skillfully took advantage of techniques and features in Chinese traditional painting, architecture, sculpture, folk art, and craft. Through their practices, they not only flourished with their own art styles, but also brought vitality to Chinese traditional aesthetics.

[1] Yong Wang, A Chinese-foreign Exchange History of Fine Arts (Beijing: China Youth Press, 2013).

王镛. 中外美术交流史. (北京: 中国青年出版社, 2013).

[2] Jianyi Jichuan, “Chinese Modern Comics: Zikai Feng and Takehisa Yumeji,”The 21 Century (2002).(Article title translated by the author.)

吉川健一. “中国近代漫画:丰子恺与竹久梦二.” 二十一世纪, 2002.

[3]长兴县图书馆. “蔡皋:绘本是安放我心思的地方.” Sohu. December 29, 2017. Accessed December 15, 2020.

https://www.sohu.com/a/213522304_784932

[4] Ibid.

[5] Tadashi Matsui and Gao Cai, The Story of Taohuayuan (Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2009). (Title translated by the author.)

松居直与蔡皋. 桃花源的故事. (上海: 上海人民美术出版社, 2009).

[6] Yuanming Tao, Tao Yuanming Ji (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 1979).

陶渊明. 陶渊明集. (北京: 中华书局, 1979).

[7] “Shadow Play” Wikipedia. Accessed December 15, 2020.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shadow_play?wprov=sfla1

[8] Geo Cai, June 6th (Changsha: Hunan Juvenile and Children's Publishing House, 2016).

蔡皋. 晒龙袍的六月六. 长沙: 湖南少年儿童出版社,2016.

[9] Liang Xiong, The Little Stone Lion (Jinan: Tomorrow Publishing House, 2007).

熊亮. 小石狮. (济南: 明天出版社, 2007).

[10] 张金杰. “国际安徒生奖公布获奖者 中国绘本画家熊亮入围” Chinaqw. March 27, 2018. Accessed December 15, 2020.

http://www.chinaqw.com/zhwh/2018/03-27/183675.shtml

[11] Liang Xiong, The 24 Solar Terms (Beijing: New Star Press, 2015).

熊亮. 二十四节气. (北京: 新星出版社, 2015).