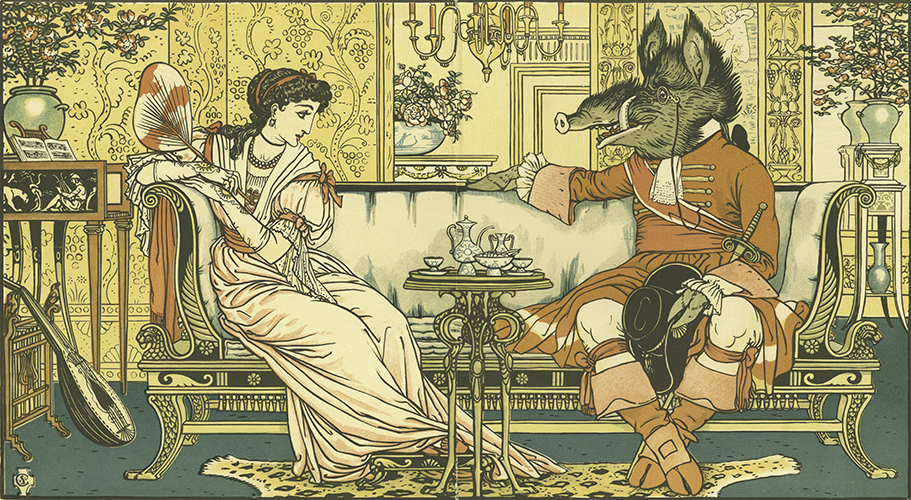

Fig. 1. Walter Crane, “At last he turned to her and said, ‘Am I so very ugly?’,” 1875

Many of the fairy tales that remain popular today first appeared in collections published by Charles Perrault, the Brothers Grimm, and Hans Christian Andersen. The stories, however, evolved from folklore passed down for many generations. Fairy tales typically involve a childlike figure who encounters a hindrance on what should be a simple journey from point A to point B. The hero or heroine’s typical antagonists include a trickster, an evil stepmother, and one of an assortment of wicked witches who sulk in castles, ride on brooms, or threaten to bake children alive in houses made of candy. Other creatures in fairy tales can be playful, even impish. Though they do not typically play a central role in the story, fairies, elves, sprites, and boggarts (goblins who terrorize the British countryside) may enjoy lighthearted encounters with the main character.

Fig. 2. Annie Stegg Gerard, Tinker Bell, 2016, © Annie Stegg Gerard

Comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell compared fairy tales to stories from classic mythology that were designed in a way a child could understand. “Fairy tales are told for entertainment,” he wrote. “But even though there’s a happy ending for most fairy tales, on the way to the happy ending, typical mythological motifs occur—for example, the motif of being in deep trouble and then hearing a voice or having somebody come to help you out. . . . All of these dragon killings and threshold crossings have to do with getting past being stuck.”[1]

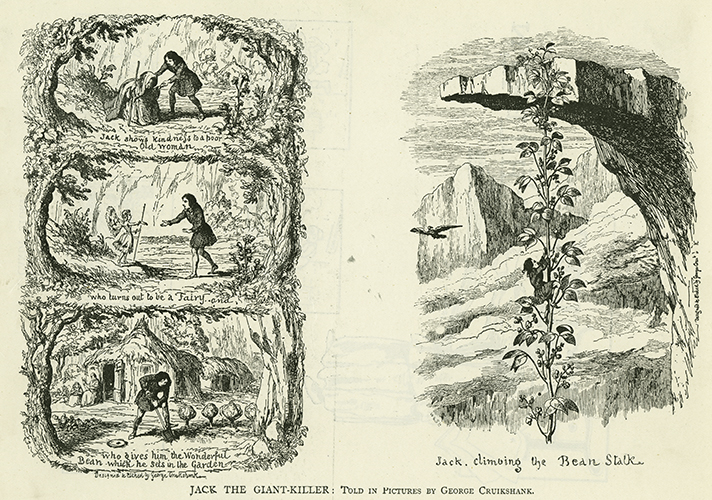

Fig. 3. George Cruikshank, Jack the Giant-Killer, 1894

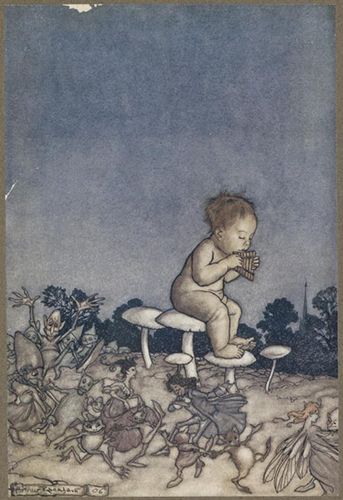

The Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung posited that a common archetype in these stories is the hero’s journey to venture away from home, fight a battle, achieve self-discovery, and return home changed. Peter and Wendy, J. M. Barrie’s 1904 fairy-tale play, delivers a twist to this classic story line. Symbolizing Pan, the Greek god of the wild, the main character does not want to grow up. He assists other “Lost Boys” in remaining childlike for a time, but “when they seem to be growing up, which is against the rules, Peter thins them out.”[2]

Fig. 4. Arthur Rackham, Peter Pan in Faerie Orchestra, 1906

Peter Pan isn’t just resisting the hero’s journey himself; he is stopping others from their own self-discovery. The reader of Peter and Wendy is left to presume that Peter keeps his cadre of Lost Boys in perpetual youth by offing the older ones as younger ones arrive. In contrast to Joseph Campbell’s description, Peter Pan isn’t involved in “dragon killings and threshold crossings,” but instead kills the hero before the journey has begun. Later versions of the story were revised and omit any reference to Peter Pan getting rid of his aging cohorts.

Fig. 5. Tony DiTerlizzi, Peter Pan, 2006, © Tony DiTerlizzi

The story “Red Riding Hood” does involve a heroine’s journey, but it too puts a twist in the self-discovery angle. Though the basic plot of the story is centuries older than any published form, Charles Perrault released the first definitive version, “Le Petit Chaperon Rouge,” in the fairy-tale compendium Histoires ou Contes du temps passé. Avec des Moralitez, published in France in 1697 and in the United States in 1729 (as Histories, or Tales from Past Times).

In Robert Samber’s original, 1729 translation of the United States edition, the story ended with the wolf eating both Red Riding Hood and her grandmother: the end—that’s it. A moral followed the tale’s conclusion: “Growing ladies fair, / whose orient rosy blooms begin t’appear . . . / It is no wonder then if, overpowered, / So many of them has the Wolf devoured.”[3]

Far from the heroine she became in later versions, Perrault’s Red Riding Hood served as a stark warning to pubescent females of the dark desires of the male of her species. The sanitized version familiar to contemporary audiences was written by Lydia Very and released in an 1863 edition—die-cut in the shape of Red Riding Hood. In Very’s tale, as the wolf is about to eat Red Riding Hood “like a bird,” a hunter shoots the beast. The moral has also changed, imploring girls to “mind your mother’s word!” and not speak with strange men, lest they too be taken by the wolf.

Fig. 6. Gustave Doré, “‘Oh, granny, your teeth are tremendous in size!’ ‘They’re to eat you!’—and he ate her,” 1865

The Brothers Grimm also retold the tale, in a story titled “Rotkäppchen,” or “Little Red Cap,” in their 1812 book Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales). However, the book was revised numerous times between 1812 and 1857. Desiring a wider audience, Wilhelm Grimm refined and sanitized the tales over several editions, and the final tales differ substantially from the original versions.[4] The first English translation of the Grimms’ stories, German Popular Stories Translated from the Kinder- und Hausmärchen, Collected by M.M. Grimm, from Oral Tradition (1823–24), was groundbreaking—not only because the book changed the way in which children’s literature entertained children but also because it featured the first great children’s book illustrations, etchings by George Cruikshank.[5]

In the Grimms’ original story, the wolf had already eaten the grandmother and Little Red Cap when a passing huntsman spied the wolf and, suspecting the wolf has eaten the grandmother, “took some scissors and cut open the wolf ’s belly.” After Little Red Cap and the grandmother escaped from the wolf ’s stomach, Little Red Cap filled the wolf’s body cavity with stones. The wolf died, the huntsman skinned it, and “all three were delighted.”

Fig. 7. Miranda Meeks, Little Red, 2014, © Miranda Meeks

The tale of Red Riding Hood has since been revisited many times, even on screen and stage, including in Tex Avery’s ribald animated short Red Hot Riding Hood (1943) and Stephen Sondheim’s 1986 musical Into the Woods. It has appeared in print in innumerable editions, with artwork by such illustrators as Walter Crane (1875), Arthur Rackham (1909), Jessie Willcox Smith (1911), Edmund Dulac (1912), Harry Clarke (1922), and Jerry Pinkney (1997).

Fig. 8. Henry Le Jeune, Cinderella, 1874

Among the other popular characters Perrault and the Grimms introduced were Cinderella and Snow White. Variations on the archetypal character Cinderella have been shared around the world for centuries, but the most familiar version was first published in Charles Perrault’s seminal fairy-tale compilation from 1697. “Little Snow White” first appeared in the 1812 edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen. In this version, the evil queen is Snow White’s “godless mother,” though later editions omitted this portrayal, “clearly because the Grimms held motherhood sacred,” one scholar asserts.[6]

Fig. 9. Albert Tschautsch, Snow White, 1892

Fig. 10. Cory Godbey, Snow White, 2019, © Cory Godbey

The Grimms’ original story “Rapunzel” would be familiar to today’s readers—to a point. A young prince pleads with the title character to allow him to climb up into the tower in which she is held by a sorceress, or fairy, and something unexpected (or perhaps not) happens:

She let her hair drop, and when her braids were at the bottom of the tower, he tied them around him, and she pulled him up. At first Rapunzel was terribly afraid, but soon the young prince pleased her so much that she agreed to see him every day and pull him up into the tower. Thus, for a while they had a merry time and enjoyed each other’s company. The fairy didn’t become aware of this until, one day, Rapunzel began talking and said to her, “Tell me, Mother Gothel, why are my clothes becoming too tight? They don’t fit me any more.”

“Oh, you godless child!” the fairy replied.[7]

The tale ends with the prince attempting suicide and ending up blinded. Naturally, the Grimms removed the pregnancy from future revisions and made the tale much more romantic.

Many fairy tales feature animals that assist or guide the protagonist (in contrast to the Big Bad Wolf). The Grimm Brothers’ tale The Two Brothers contains not only a terrible many-headed dragon but a menagerie of helpful animals, including a hare, a bear, a fox, and a lion. Carl Jung explained, “Again and again in fairytales we encounter the motif of helpful animals. These act like humans, speak a human language, and display a sagacity and a knowledge superior to man’s. In these circumstances we can say with some justification that the archetype of the spirit is being expressed through an animal form.”[8]

Fig. 11. Greg Hildebrandt, The Mock Turtle, 1990, © Greg Hildebrandt

Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) is replete with animals (most ambiguously helpful), from the White Rabbit to the Cheshire Cat to the Mock Turtle. An original story rather than an updated folktale, it sent its heroine on a topsy-turvy journey that has no purpose other than the reader’s entertainment. Alice’s passageway to her adventure, through a burrow, inspired the phrase “down the rabbit hole,” a metaphor for entry into a strange, disorienting, or seemingly inescapable situation.

Like other popular children’s stories, the Alice series has appeared in many print editions, but the original illustrations by John Tenniel remain iconic. A popular cartoonist at Britain’s Punch magazine since 1850, Tenniel first met Lewis Carroll in 1864. He agreed to create forty-two illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland after reading Carroll’s manuscript. Carroll gave the artist very specific instructions concerning every aspect of the illustrations. When Tenniel had completed the forty-two drafts, Carroll liked only one, the drawing of Humpty Dumpty. Nonetheless, their collaboration went forward. The most accurate representations of the finished illustrations are from the engravings, since Tenniel produced only preliminary drawings, which he then transferred to the wood engraving block, where he made his final version, “drawing with the hardest pencils directly on the wood.” After production, many of the blocks were destroyed.[9]

Fig. 12. Sir John Tenniel, The Mad Tea Party, 1865

For the first printing of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Carroll approved Clarendon Press for a print run of two thousand copies. However, Tenniel took issue with the sample print Clarendon sent to Carroll, deeming it “altogether unacceptable” and insisting that Carroll cancel the order. Carroll was worried that starting over with a new printer would take so long the book would no longer interest his young friends, who “are all grown out of childhood so alarmingly fast.”[10] Despite this worry, as well as the financial loss, Carroll shifted the responsibility for printing to Richard Clay, a London printing house better equipped than Clarendon to complete the job. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was finally printed and issued in November 1865. Carroll published a sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, in December 1871 (dated 1872).

Fig. 13. Scott Gustafson, A Mad Tea Party—Alice in Wonderland, 1993, © Scott Gustafson

The Alice stories have been adapted many times since their initial publication. Walt Disney released his animated version in 1951; a famously surreal film adaption, Alice, was released in Czechoslovakia in 1988; and the Disney company revisited the story through live-action films Alice in Wonderland (2010) and Alice through the Looking Glass (2016).

[1] Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth (New York: Anchor Books, 1991), 167.

[2] J. M. Barrie, Peter and Wendy (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911), 76.

[3] Charles Perrault, The Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault, trans. Robert Samber (London: Folio Society, 1998), 31.

[4] Jack Zipes, ed., The Original Folk & Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014), introduction.

[5] Michael Patrick Hearn, Myth, Magic, and Mystery (Boulder, CO: Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 1996), 7.

[6] Zipes, Original Folk & Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm, introduction.

[7] Ibid., 39.

[8] Carl Jung, The Collected Works of Carl Jung, vol. 9, pt. 1: The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, trans. R. F. C. Hull (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969), 231.

[9] Hearn, Myth, Magic, and Mystery, 9.

[10] Susan E. Meyer, A Treasury of the Great Children’s Book Illustrators (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1983), 72.

Note: This essay first appeared in the Norman Rockwell Museum exhibition catalogue, Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration, by Jesse Kowalski (New York: Abbeville Press, 2020.)