Mary Hallock Foote (née Hallock) was born in 1847, when the American West was fast becoming a popular subject for artists as well as writers, or what has been called “western American narrative painting,” and the first phase of its popularity was prevalent from the 1830s through the 1860s in the work of such artists as George Caleb Bingham, George Catlin, John Mix Stanley, and Alfred Jacob Miller.[1] They were followed by the Post Civil War generation, which included Henry Farny, Charles Russell, Frederick Remington—and the little-known, Mary Hallock Foote, who stood out not just because she was a woman, but because she lived the life she wrote about and illustrated; in a way, she was the forerunner of that celebrated novelist of pioneer life, Willa Cather (1873-1947).

Mary Hallock Foote (née Hallock) was born in 1847, when the American West was fast becoming a popular subject for artists as well as writers, or what has been called “western American narrative painting,” and the first phase of its popularity was prevalent from the 1830s through the 1860s in the work of such artists as George Caleb Bingham, George Catlin, John Mix Stanley, and Alfred Jacob Miller.[1] They were followed by the Post Civil War generation, which included Henry Farny, Charles Russell, Frederick Remington—and the little-known, Mary Hallock Foote, who stood out not just because she was a woman, but because she lived the life she wrote about and illustrated; in a way, she was the forerunner of that celebrated novelist of pioneer life, Willa Cather (1873-1947).

Foote was born in Milton, New York, in the Hudson Valley, a short ferry ride across the river to Poughkeepsie where she attended the Female Collegiate Seminary.[2] In the winter of 1866-67, because of her interest in art, she enrolled in The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, or The Cooper Union, which in her day was known as The Cooper Institute. Located in New York City at Cooper Square and Astor Place, the school’s founder, Peter Cooper, believed in an education free and open to all who qualify, regardless of race, gender, or social status. To Mary Hallock Foote it was ideal, and she spent three years there studying with William Rimmer (1816-1879) and William James Linton (1812-1897). Rimmer, who was also the school’s director, was an eccentric painter, sculptor and writer (Elements of Design, 1864 and Art Anatomy, 1867), and a brilliant teacher, as was Linton, who was a political activist, painter, and wood-engraver. Foote credited them as her most important influences.[3] Linton was impressed by her designs for engravings, and it was through him that she received her first commission: for Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Hanging of the Crane, in 1874. It was while at Cooper that Foote also met Helena de Kay, who became a life-long friend, about whom in 1917 she would write her novel, Edith Bonham. Helena de Kay’s fiancé was Richard Watson Gilder, the editor of Scribner’s Magazine and later of the Century. Through his admiration of her work, as well as their friendship, Gilder commissioned many of Mary Hallock Foote’s illustrations and published her stories.[4] She specialized in drawing for wood block prints, and quickly developed a good reputation in the publishing business, but it was when she went to the West that she really hit her stride.

In 1876 Mary Hallock married a mining engineer, Arthur De Wint Foote, and followed him throughout the West as he pursued his career: to various mining camps in Colorado and South Dakota, to Boise, Idaho where he worked on a massive irrigation project and where they lived for twelve years, before moving on to Grass Valley, California, where he managed the North Star mine until his retirement. Despite the constant moving around, keeping an open house wherever she went and entertaining important guests, as well as raising three children, Mary Hallock Foote wrote and illustrated many novels and numerous short stories, often supporting the family during rough times. Her frontier stories were compared to those of her fellow New Yorker Bret Harte (1836-1902), whose work she illustrated, and she was acclaimed as one of the best-known women illustrators of the 1870s and ‘80s. It was in Boise that she did her best and most successful work, and where she would become something of a celebrity. A collection of her prints is on permanent exhibition at the Boise Public Library, gift of the Columbian Club, many of which are included in this article (the club was responsible for establishing library service in the town), and in 1916, the town of Boise held a special celebration in Mary Hallock Foote’s honor.[5]

By the time of the Boise event, the Footes were living in Grass Valley, California to which they had moved in 1896, and about which in 1915 Foote wrote the novel, The Valley Road. The Footes lived in a house called “North Star” which was designed for them in 1905 or 1906 in the California Arts and Crafts style by Julia Morgan (1872-1957), the first woman to become a licensed architect in California. It was a perfect alliance between architect and client, and it was where Mary Foote wrote her memoir, A Victorian Gentlewoman in the Far West. From the time it was built to 1968, the house was lived in by members of the Foote family. It is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[6]

She wrote her last novel in 1919, and in 1932, the Footes moved to Hingham, Massachusetts, one of the oldest towns in New England, to live with their daughter, Betty. Mary Hallock Foote died there at the age of ninety-one.

After her death, or maybe even before that, her reputation faded and she disappeared from public view. She was, perhaps, the victim of her own reserved and elegant style. She did not depict the life of the trapper, the cowboy on a round-up, the buffalo hunter, or the American Indian; the bugle call style of Frederic Remington was not for her. And even though she lived amidst the rough life of the mining camps, and even though she did not want to be known as “woman” illustrator, her stories and illustrations were seen through the eyes of “A Victorian Gentlewoman in the Far West,” the title of her reminiscences. The illustrations, A Pretty Girl in the West, and The Orchard Windbreak in the collection of the Boise Public Library are examples of that.

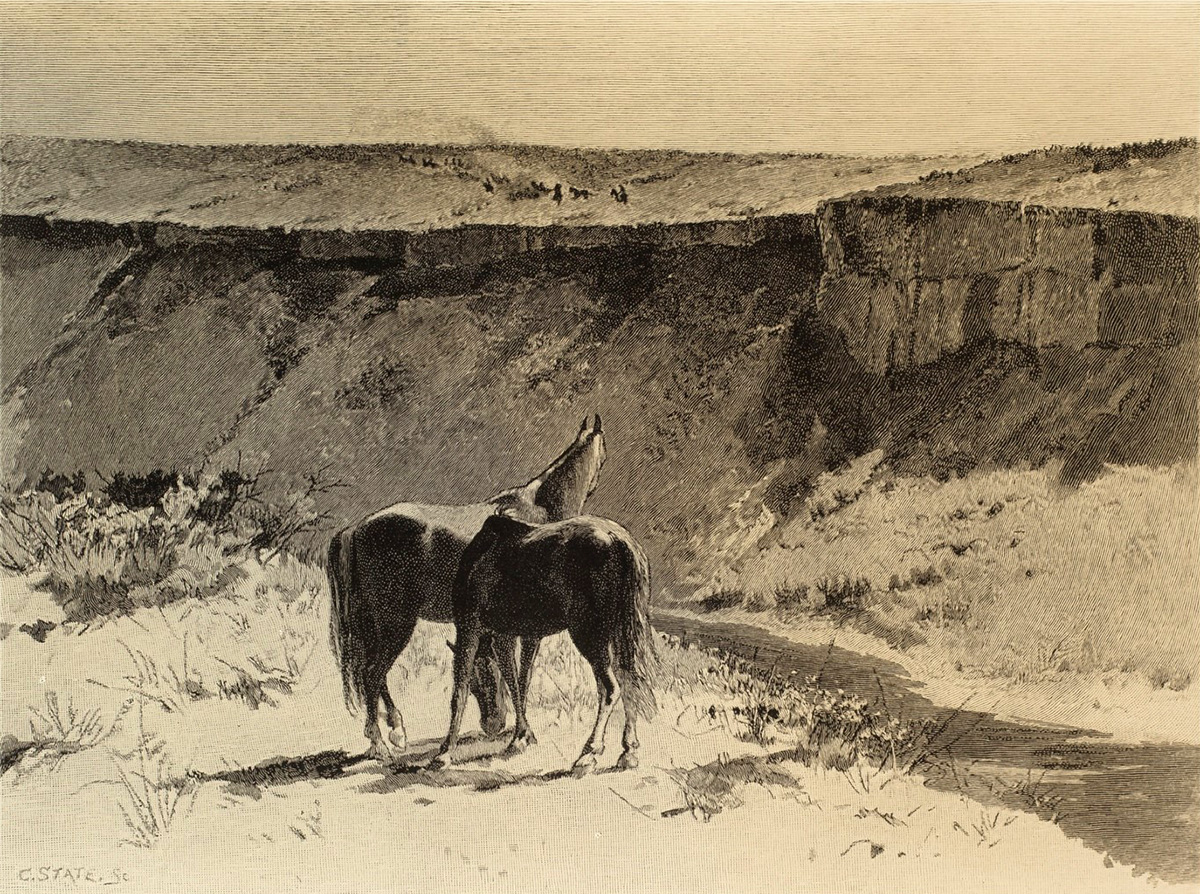

The latter can be interpreted, perhaps, as the taming of the wild, or as a “civilizing” act to encourage the settlement of this beautiful part of the country. Even the vast epic landscape of the West in such illustrations as Hunting with Horse and Dog, and Two Horses is treated with a certain intimacy and reserve.

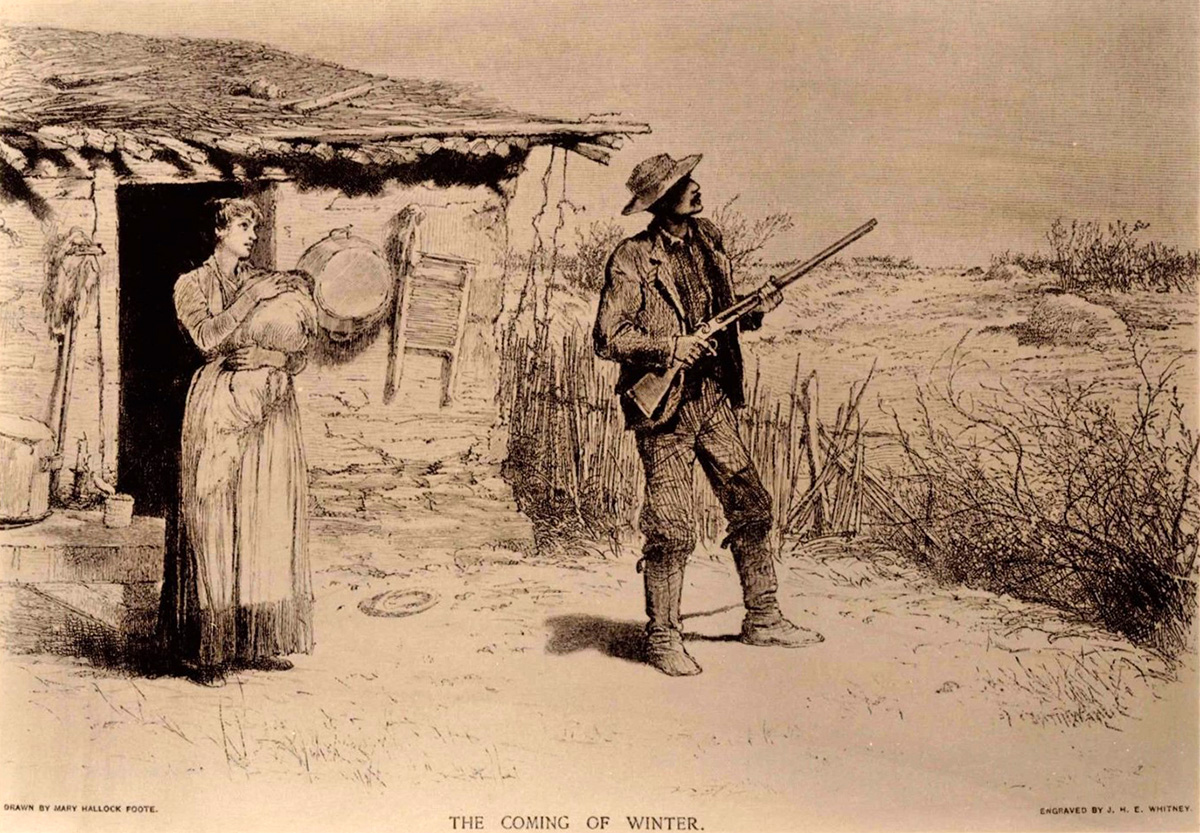

Even in both the original drawing (an excellent model of her skill and style) and the final print of The Coming of Winter, the former in The Delaware Museum of Art and the latter in Boise, there appears to be anticipation, but not dread of a very difficult season. And in the extraordinary drawing in the collection of The New Britain Museum of American Art, titled She Slipped the Mantle From Her Shoulders, from the novel Coeur d’Alene which set in the mining town of the same name, against the backdrop of a miners’ war, the heroine is depicted as caregiver, a Victorian view of the role of women.

In addition to the illustrations in the collections at the Boise Public Library, The Delaware Art Museum, and the New Britiain Museum of American Art, examples of her work can be found in the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as the Cabinet of American Illustration at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Despite all that, it was not until 1972 and the release of her reminiscences, edited by Rodman Paul and published by the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, that a revival of inerest in her work began. It was not only about time, but overdue—and despite an impressive bibliography, she is still an artist who should definitely be much better known.[7]

Richard J. Boyle is an art historian with a specialty in American Art and Culture; former museum director (The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia from 1973 to 1983). He also served as a faculty member in the art history department at Temple University, Philadelphia from 1983 to 1996, and has served on the Low Illustration Committee of the New Britain Museum of American Art from ca.2007 to 2019. We appreciate his important contribution of this essay.

Notes, Bibliography, and Acknowledgements

[1] Peter H. Hassrick, American Frontier Life: Early Western Painting and Prints (New York: Abbeville Press, Inc., 1987), 6.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary Hallock Foote

[3] Roland Elzea and Iris Snyder, The American Illustration Collections of The Delaware Art Museum (Wilmington, DE: The Delaware Art Museum, 1991) 163.

[4] Helenadekaygilder.org/maryfoote/index.htm

Re: the Foote illustrations in the Boise Public Library: there is some controversy; they have been variously described as originals in 1920 and 1939, as reproductions in 1921, as copies in 1931, and as proofs in 1932. See Boise City Dept. of Arts and History, Boise Public Library, History Request Form #CHR 16015. It also brings to mind the late illustrator and historian of illustration, Murray Tinkelman, who once said to me, “an illustrator creates art for reproduction. . . . an illustration might be a work of art where the original is the reproduction.”

[5] On the architect, Julia Morgan and North Star House, see https//en.wkipedia.org/wikiped1a/Julia Morgan

[6] Paul Rodman, ed., Mary Hallock Foote, A Victorian Gentlewoman in the Far West: The Reminiscences of Mary Hallock Foote (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1972)

ADDITIONAL SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Wallace Stegner, Angle of Repose (New York: Doubleday, 1971). A Pulitzer Prize novel based on the lives of Mary Hallock and Arthur DeWint Foote.

Walt Reed, The Illustrator in America 1860-2000 (New York: The Society of Illustrators, 2001) 34.

Shelley Armitage, “The Illustrator as Writer: Mary Hallock Foote and the Myth of the West,” Under the Sun: Myth and Realism in Western American Literature (Troy, NY: Whitson, 1985) 150-174.

Lee Ann Johnson, Mary Hallock Foote (Boston: Twain Publishing, 1980).

Hugh Chisholm, ed., Foote, Mary Hallock, Encyclopedia Britannica, 10 (11th edition), Cambridge University Press, 625.

Sue Rainy, “Mary Hallock Foote, A Leading Illustrator of the 1870s and ‘80s,” Winterthur Portfolio, 41 (2/3), June 2007: 97-140.

Darlis Miller, Mary Hallock Foote, Author-Illustrator of the Old West (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002). This is part of a series on significant westerners, including John Muir, Annie Oakley and the amazing Native American, woman, Red Cloud.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks to the following people for making it possible to publish the Mary Hallock Foote works in their collections, as well as providing the very useful information about them: Keith Gervaise, Collections Manager, New Britain Museum of American Art, New Britain, CT; Erin Tohill Robin, Chief Registrar, Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, Delaware; Ari Zickau, Information Services Librarian, Boise Public Library, as well as the Boise Public Library Administration, Boise, Idaho; and Stephanie Plunkett, Deputy Director and Chief Curator, Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, MA, who asked me to write about this remarkable artist for the Museum’s Illustration History Website.