PICTURING RAMONA

ILLUSTRATIONS TO HELEN HUNT JACKSON’S NOVEL OF CALIFORNIA

Michael K. Komanecky

The story may sound familiar. An experienced and successful author, raised in New England and whose father was a university professor, writes a novel that takes the country – and people in other places around the world – by storm, selling huge numbers of books requiring one printing after another. Reporters cannot seem to stop writing articles about the book, and it is soon made into a movie with major Hollywood stars. What’s more, readers all over the United States and even abroad are so taken by the story that they seek out the sites where the novel’s events took place, distant though they may be from their homes. Special tours are arranged to visit these places, with guides expounding on the sites’ histories and how they relate to the book. So many tourists flock to them that their owners are sometimes overwhelmed and restrict access. Controversies arise over what is fact and what is fiction, generating still more articles and books portending to set things straight. And whatever the foundation in reality for certain elements of the novel, some seem readers unable, or unwilling, to separate fact from fiction. The debate occasionally becomes heated, but it only seems to fuel interest in the book, bestowing upon its author a not entirely desired fame.

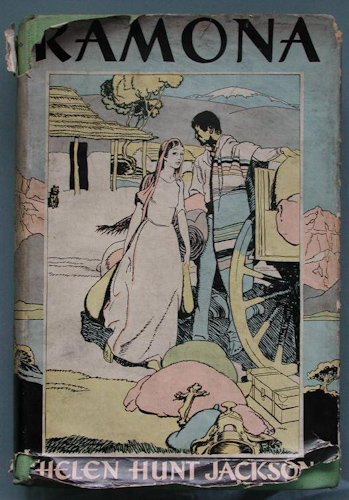

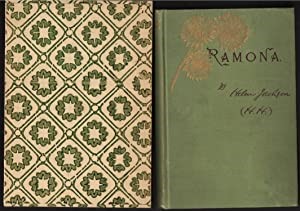

While today’s readers of popular fiction will probably recognize Dan Brown’s 2003 novel, The Da Vinci Code, as fitting this description, few if any would think of the book written more than a century earlier that generated a similar and, truth be told, far bigger response: Helen Hunt Jackson’s 1884 novel, Ramona: A Story. Her book about the tragic love affair between Ramona, the orphaned daughter of an Indian mother and Scottish father, and Alessandro, Luiseño son of the chief to a band of Indians at California’s Mission San Luis Rey, quickly proved to be an enormous popular success. Like many novels of its day, it first appeared as a series of magazine articles, in this case a chapter every week between May 15 and November 6, 1884 in The Christian Union.[1] In what seems to have been a conscious marketing decision on Jackson’s part, and probably her publishers, it was then released in book form by Roberts Brothers of Boston in November just as the magazine series came to a close (Fig. 1).[2] Within three months it sold seven thousand copies, and by the time of Jackson’s death just ten months after it was released, a total of fifteen thousand had been sold.[3] By 1893, Ramona was in sixty-eight percent of America’s public libraries.[4] It became so popular that even though the Los Angeles Public Library owned one hundred and five copies of the book in 1914, its readers still had to make a reservation to obtain one.[5] It is reported that the Library had to purchase a thousand additional copies to try to meet the demands of its borrowers.[6]

Fig. 1. Cover of 1884 edition of Ramona: A Story, Helen Hunt Jackson Collection, Charles L. Tutt Library, Colorado College

Just as quickly Ramona found an audience abroad, with Macmillan publishing it in London in 1884 to be followed by editions just before 1900, in 1911, and 1914.[7] In 1886 a German translation was published in Leipzig;[8] a French edition was published in Paris in 1887;[9] Spanish editions were published in New York in 1888, Mexico in 1889, Buenos Aires around 1900, and Havana and Madrid in 1915.[10] Its primary market, however, was in the United States, where Roberts Brothers and later other publishers sought to take advantage of the potential profit from Jackson’s story: twenty-one editions were published between 1884 and 1939.[11] This love affair with Ramona has continued unabated with more than three hundred printings of the novel,[12] recent editions appearing in 2002 and 2005, each containing not just one but two authoritative scholarly analyses.[13]

Ramona’s grip on the public was not limited, however, solely by the appeal of its text as fiction. Almost immediately after its initial publication, a seemingly irrepressible fascination arose for discovering the “real” characters and places that inspired its author. In 1887 Roberts Brothers released an edition that included an appendix by Edwards Roberts, “Ramona’s Home: A Visit to Camulos Ranch, and to the Scenes Described by ‘H.H.’” It acknowledged Jackson’s indebtedness to the California ranch that she used as the model for Ramona’s home, one of many real-life sources that had informed her novel. The public’s interest in knowing more about Jackson’s inspirations quickly grew into an obsession, aided by a series of books and articles that attempted to satisfy the curiosity of Ramona’s growing number of readers.[14] A January 1887 piece in the Los Angeles Times first identified Camulos Ranch as the site that Jackson used as the setting for her novel.[15] In 1888, Charles Fletcher Lummis, historian of the Southwest and no stranger to the benefits of clever promotion, published his own small pamphlet, Home of Ramona, in which his cyanotype photographs showed readers the very house Jackson visited.[16] One author after another sought to identify the places that figured in the novel, including where Ramona was born and where she was married. A controversy even arose as to whether Camulos or another site, Rancho Guajome, was the one that Jackson used as the model for her description of the Moreno ranch.[17] The people whom Jackson actually or purportedly met in the course of her travels in California from late 1881 to mid-1883 also became the targets of these professional and amateur sleuths. Efforts were made to identify who the “real” Ramona was, as well as the novel’s other main characters, including the killer of Ramona’s Indian husband. From 1900 on, and particularly in the 1910s, the momentum of stories and books gathered strength, leading to a virtual industry that brought thousands of visitors to California to visit every possible site related to the novel in search of what now seems to have been the Ramona holy grail. There was even a Ramona cookbook, published in 1929.[18]

Ramona quickly attracted interest in dramatic circles as well. In 1887, just three years after the novel was published, Ina Dillaye published the first script for a theatrical presentation of Ramona,[19] followed by Charles Albert Norcross’s sixty-eight page script in 1888,[20] and J. Jones’, with music by L.F. Gottschalk, in 1897.[21] In 1905 Virginia Calhoun, who had purchased the stage rights to the novel, presented a five-hour long production in Los Angeles which apparently tested the endurance of even the most fervent admirers of Ramona.[22] It appears, too, that visitors to Rancho Camulos were occasionally treated to abbreviated dramatic presentations of the novel.[23] Ramona’s ultimate stage potential was eventually seized by dramatist and pageant producer Garnet Holme, who adapted the novel to what has become one of the longest-running outdoor stage presentations in the United States. First presented in 1923 in a natural amphitheater outside the rural San Jacinto County village of Hemet, Holme’s production, with the exception of a hiatus in the depression year 1933 and again for four years during World War II and again during the Covid-19 pandemic, has been held annually ever since. In addition to reaching thousands each year, it provided opportunities for aspiring young actors to play the roles of Alessandro and Ramona, among them Victory Jory in 1932 and in 1959 Raquel Tejada, better known by her later stage name, Raquel Welch.[24]

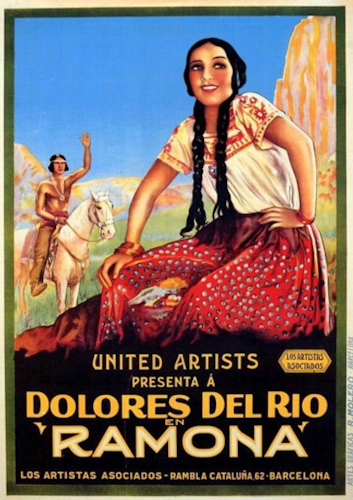

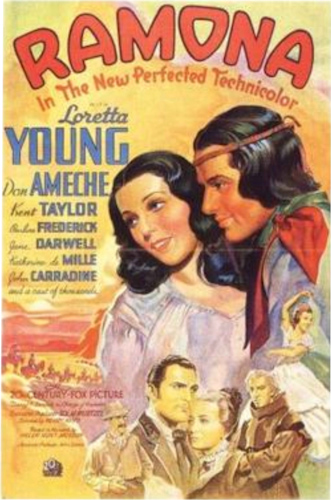

California’s emerging film industry also took advantage of Ramona’s popularity. The young actor David Wark Griffith, who joined American Mutoscope & Biograph Company in 1908 as an actor and shortly thereafter began the directing career that made him famous, had played Alessandro in Calhoun’s 1905 stage production.[25] One of his early films was Ramona, which he made in 1910 with the seventeen-year-old Mary Pickford in the title role. Griffith, no doubt aware of the enormous public interest in the sites that inspired Jackson, shot his film at Rancho Camulos and cited it in the credits, the first such location credit in American film.[26] Clune Productions released its version of Ramona in 1916, which was followed by one in 1928 with famed star of American and Mexican cinema, Dolores del Rio, who introduced Mabel Wayne’s song “Ramona,” with lyrics by Wolfe Gilbert. In 1936 Twentieth Century Fox released another version, its first all Technicolor film, with Loretta Young as Ramona, Don Ameche as Alessandro, and John Carradine as the nefarious Jim Farrar, Alessandro’s killer. This one, too, included musical numbers, among them Wayne’s and Gilbert’s by now long-popular “Ramona.” The film was shot on location at Warner Hot Springs and the Mesa Grande Indian Reservation in San Diego County, and its Indian extras were said to have been descendants of the very Indians that featured so prominently in Jackson’s novel.[27] The first Spanish-language version appeared in 1946 when the Mexican film company Promex made Ramona, directed by Victor Urruchúa and starring Esther Fernández as Ramona and Antonio Badú as Alessandro.[28]

The enormous public appetite for all things Ramona was seemingly met at every turn by an entrepreneurial spirit to satisfy it. With it came other efforts to enrich Jackson’s novels by providing its readers with ways to visualize it, literally. In addition to their portrayal in theater and film, Ramona’s characters, settings, and locales were brought to life repeatedly as illustrations to her novel. The evolution of this imagery and its relation to her text, however, has not been studied in any meaningful way.[29] This article will explore the origins of these illustrations, their chronology, their creators, and, most importantly, how these illustrations were employed to amplify the novel’s narrative features and characters. It must be said from the outset that the existence of so many versions published here and abroad make a completely exhaustive review of all of them a herculean task,[30] yet key examples are well known and provide more than ample evidence to consider how text and image interacted in Jackson’s famed story, and how these images address, or ignore, issues of gender and colonization that are central to Jackson’s novel.

THE ORIGINS OF RAMONA: A STORY

Jackson’s concept for the novel evolved from a series of trips she made to California in the early 1880s. Her 1881 book, A Century of Dishonor: A Sketch of the United States Government’s Dealings with Some of the Indian Tribes, had established her as a nationally important advocate for Indian rights and led to an invitation from the new Century Magazine, the successor to Scribner’s Monthly, to go to California and write a series of articles based on her experiences there. Although she had been in California in 1872 for New York Independent[31]and was an experienced travel writer, Jackson felt the need to familiarize herself with her new subject more deeply. Following the suggestion of her author friend Edward Everett Hale, she undertook research at New York’s Astor Library, reading, among other things, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Jesuit histories of California as well as John Russell Bartlett’s report from his 1850-53 survey to establish the new boundary between the United States and Mexico.[32] Thus immersed in her subject, Jackson left for California on the Southern Pacific’s new direct line to Los Angeles, arriving there on December 18, 1881 and stayed in California until she departed for her Colorado Springs home in late July 1882.[33] Jackson’s experiences during her travels would have an enormous impact on her and the subsequent direction of her literary career, far beyond the articles she was commissioned to write for Century.

Through a series of introductions arranged by various friends and acquaintances, Jackson gained entry into Californio life, establishing relationships and visiting places that would provide the essential raw material for Ramona. Among the most important friends she made were Mexican-born Antonio Colonel and his wife Mariana. Colonel had held several positions in both the Mexican and subsequent American governments in California, including inspector of the missions under the former. His familiarity with southern California’s mission Indians, not unexpectedly, greatly interested Jackson and with his help she traveled to several Indian villages over the next few months. She went to the Luiseño villages of Pala, Temecula, Apeche, Pauma, Rincon, Pachanga, Potrero, and La Jolla; the Cupeño village of Agua Caliente (Kupa); the Ipai villages of Mesa Grande and Santa Ysabel; the Serrano village of Soboba; and a number of Cahula villages as well. Like so many visitors to California in the second half of the nineteenth century, she visited its Franciscan missions, including San Diego, San Gabriel, San Juan Capistrano, and San Luis Rey. Like nearly all of California’s twenty-one missions, they were in ruinous condition. The only exception was Santa Barbara, at that time a Franciscan college and prosperous in comparison to the other missions. There, Jackson did further research in the college’s library, one of the most important repositories of Franciscan-era documents relating to the history of California’s missions. These sojourns to the most visible reminders of the Franciscan missionary enterprise also introduced her to its legendary founder, Junípero Serra, whose painted portrait was at mission Santa Barbara.[34]

Returning to Colorado Springs in late summer of 1882, Jackson began work on her articles for Century. She wrote four in all, which appeared between May and October 1883. Their scope spanned California’s history from the arrival of the Franciscans, with particular emphasis on Serra, to modern agricultural industries in California to the current status of its Indians.[35] Her piece on this last subject, building as it did upon her contributions in A Century of Dishonor, further elevated her status an expert and advocate on the still hotly-debated Indian question. As a result, she was assigned by the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Hiram Price, to return to California to prepare a formal report on the condition of Indians in the state’s three southernmost counties.[36] Jackson arrived in Los Angeles on February 25, 1883, joined by her friend and partner on this assignment, Abbot Kinney, a wealthy young cigarette manufacturer and Spanish-speaking world traveler who had gone with her on her previous trip in May 1882.[37] From March to May they visited eighteen villages, some of which she had visited the year before, gathering information on the indignities and injustices regularly suffered by southern California’s native peoples, not the least of which were unrelenting and unscrupulous efforts to take their land. Returning to Colorado Springs in late May, she and Kinney worked on the report until June 4, when he went back to his home in California. By July, Jackson finished the thirty-five page Report on the Condition and Needs of the Mission Indians of California, which the Government Printing Office published in January 1884. Its main recommendation was that rather than placing Indians on reservations they should be allowed to retain their lands, which Jackson noted prophetically would require protection from white settlers, farmers, and speculators who, with little effective resistance by federal Indian agents, resorted to all sorts of schemes, theft, and even murder to get what they wanted.

After completing the report, Jackson once again turned to what had been a staple in her now nearly twenty-year long career, travel writing. She wrote articles for The New York Independent, Christian Union, and Atlantic Monthly, some of which delved further into the issues in California she wrote about in the Report.[38] Only in the fall did the idea of writing a novel based on these experiences take shape. As reported by Kate Phillips in her insightful account of the novel’s evolution, since the late 1870s, Jackson had been contemplating whether fiction could serve as a better vehicle for her to promote Indian causes. She was struck in particular by the impact of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem Evangeline, and Albion Tourgée’s A Fool’s Errand, all of which seemed to suggest how powerful fiction could be in voicing protest on behalf of the dispossessed. Jackson had been the laudatory reviewer in 1881, in fact, of William Justin Harsha’s 1880 novel, Ploughed Under, which dealt with Indian reform issues near and dear to her heart. After her trips to California in 1881-82 and 1883, she became more interested than ever in writing her “Indian story.”

Jackson’s actual writing of Ramona was a story in itself. After contemplating how she might approach her subject, the entire plot came to her as she awoke one October morning in 1883. She later told a friend – Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who published an 1884 article on how the famous novel came into being – that the story came to her “in less than five minutes, as if someone spoke it” and that in the next few days it became “more and more vivid.”[39] In late November she traveled to New York, took an apartment at the Berkeley Hotel, and began to write in earnest. On November 24 she wrote Higginson that “My story is all planned: in fact, it is so thought out it is practically written.” In a flurry of productivity, Jackson wrote Ramona between December 1, 1883 and March 9, 1884, sometimes writing as much as 3,000 words a day. As she told Thomas Bailey Aldrich, she wrote it “faster than I can write an ordinary letter…It was an extraordinary experience.”

By mid-May, the first installment appeared in The Christian Union, established in 1870 in New York and whose editors were Henry Ward Beecher and Lyman Abbott. The installment began with an entreaty by Abbott and Hamilton W. Mabie: “Readers of The Christian Union will find in the present issue the first chapter of Mrs. Jackson’s story, ‘Ramona,’ the publication of which will be continued during the summer. The deepening interest and cumulative power of this story will undoubtedly create, in the later stages of publication, a large demand for earlier numbers; all, therefore who wish to read this story from the beginning will do well to send in their subscriptions at once.”[40] Whether they had a premonition of the story’s potential appeal or their statement was simply an editor’s attempt to generate interest in it and hence revenue to the magazine’s publisher, is unfortunately not known. Jackson’s intent, however, is. Sacrificing a higher fee, she chose to release her novel in the magazine in an attempt to generate, as quickly as possible, wide public interest in her story of Indian mistreatment in California.[41]

CHARTING OUT THE TERRITORY: EARLY ILLUSTRATIONS TO RAMONA

That Roberts Brothers’ first edition of Ramona released in November 1884 consisted only of Jackson’s text – without illustrations – is in no ways surprising. Rarely were first editions of novels illustrated. On the most basic level, this was a sound business decision, a testing of the waters before committing to the added expense including illustrations would require.[42] In the late 1880s, however, as the novel’s popularity grew, articles began to appear in the press about the places that were described in it. The San Francisco Chronicle, Los Angeles Times, New York Evening Post, San Diego Union, and Ventura Free Press, as well as the monthly magazines Rural Californian and Overland Monthly all ran articles on Ramona’s purported home, Camulos Ranch (or its rival, Guajome Ranch), her marriage place, the pilgrims to them, and even one on the potential of investing in real estate in Ramona country.[43] These investigations into the presumed factual bases of the novel were what spurred earlier efforts to illustrate Jackson’s novel.

It was not Ramona‘s publisher, however, who initiated these efforts. Rather, they were driven independently, and frequently took on a decidedly homespun character. In 1888 Charles Fletcher Lummis published his own pamphlet, The Home of Ramona, which contained his cyanotype photographs of the Camulos ranch and related sites. (Fig. 2).[44] These were among the very first images directly related to Jackson’s novel, and their purpose seems clearly to have been to cement in readers’ minds the “real” places associated with the life of the fictional Ramona. Lummis, an irrepressible booster of the American Southwest, was an accomplished photographer and author who had the vision, means, and recognition to produce what was a relatively professional looking publication.

Fig. 2. Charles Fletcher Lummis (American, 1859-1928), Title page to Charles Fletcher Lummis album, Home of Ramona, 1888, given to Susanita del Valle, with image of the South Veranda. Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, photCL 504. The Huntington Library

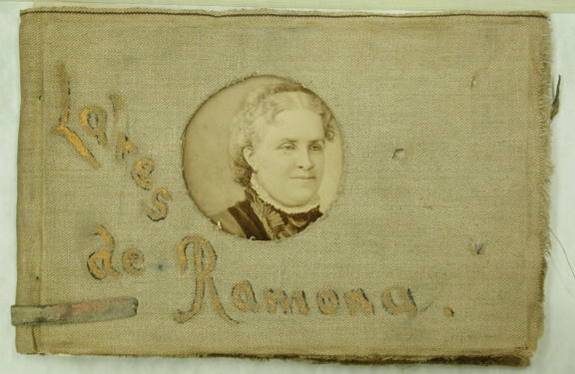

In this early rush to produce illustrated works connected to Jackson’s novel, however, they sometimes took the form of do-it-yourself efforts. In the same year as Lummis’ pamphlet, A. Frank Randall published an album of six photographs of scenes with figures posed to illustrate the novel and which included a portrait of Helen Hunt Jackson (Fig. 3).[45] Randall’s effort reflected the deep personal attachment readers felt for the novel, and he was not the only one to take matters in his own hands. In 1894, Mrs. C.B. Jones of Greenville, Texas glued a color image of Camulos’ famed south veranda on the inside front cover of her 1893 edition of Ramona.[46]

Fig. 3. A. Frank Randall (American, active 1880s), Cover from Lares de Ramona or Mrs. Helen Hunt Jackson and Ramona (Los Angeles: A.F. Randall, 1888), Library of Congress, as Album of sentimental photographs of scenes with posed figures to illustrate Ramona by Helen Hunt Jackson, LOT 3119 (F)

Even after the first illustrated edition of the novel was subsequently released in 1900 by Little, Brown & Company, some Ramona aficionados continued to produce their own illustrated versions. In 1916, Jean Woolman Kirkbride acquired an edition of Ramona published that year that contained reproductions of photographs by Adam Clark Vroman. She removed all of them, however, and replaced them with her own hand colored photographs, each protected by a tissue guard sheet with a hand lettered title – 122 photographs in all.[47] Kirkbride was nothing if not thorough, including photographs of Rancho Camulos as well as the ranch at Guajome, previously misidentified as the site that inspired Jackson in her description of the ranch on which Ramona was raised. Kirkbride also included images of missions Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, San Gabriel, San Luis Rey, San Buenaventura, San Carlos Borromeo, San Fernando, San Antonio, Santa Ines, San Juan Bautista, San Diego, and Soledad, only some of which figured in the novel.

There were also images of real-life people who erroneously had been identified as the models for certain characters in the novel as well as scenic views of places in California, not all of which are connected with the story. Kirkbride, it seems, left no stone unturned in her effort to document all that was known about the novel and its many sources, and to give its readers a familiarity with California’s distinctive natural beauty.

California photographers, in fact, led the way in producing Ramona-related illustrated books. Following Lummis’ example, another photographic documentation of Ramona sites was assembled in 1890 by Taber Photographic Company of San Francisco, containing fifteen prints including some scenes of surrounding Los Angeles.[48] Isaiah West Taber’s photographs were also sold separately with texts from the related section of the novel printed below the image, and became popular items for tourists seeking mementos of their Ramona-inspired travels.

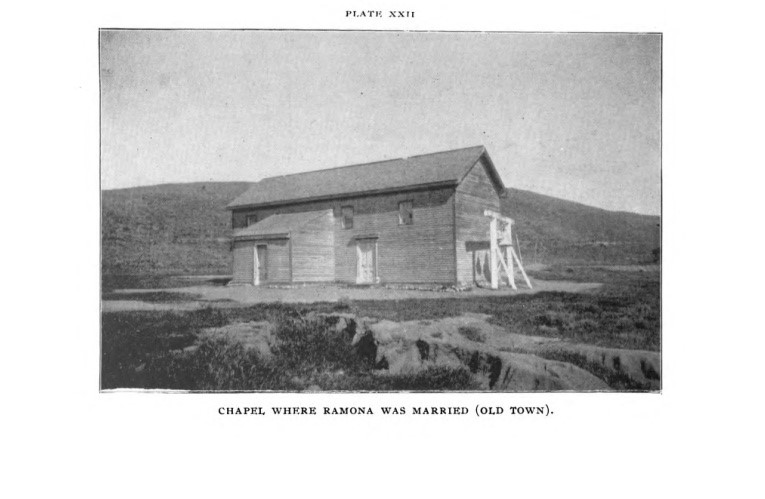

In 1899 Lummis’s friend and fellow photographer of the American Southwest, Adam Clark Vroman, published a much more ambitious book, The Genesis of the Story of Ramona: Why the Book Was Written, Explanatory Text of Points of Interest Mentioned in the Story, written with T.F. Barnes.[49] Vroman moved to California in 1892 and in 1897 and again in 1899 he accompanied expeditions of the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology to New Mexico where he photographed Indian ruins and Spanish missions. Vroman was fascinated by the missions, by then widespread romantic symbols of California’s Spanish past and between 1895 and 1905 he photographed all of the state’s missions.[50] His Ramona book contained thirty halftone reproductions made from his photographs and thus was the most luxurious and richly illustrated book yet produced for the growing Ramona market.[51] Vroman included various scenes of Rancho Camulos and its surroundings, many of which are known to have been sites that inspired those Jackson described in her novel. Some, like Vroman’s photograph of a chapel in San Diego’s Old Town, referred specifically to scenes in the novel, in this case the place where Ramona was married (Fig. 4). Vroman likely sold these photographs individually, as Taber had, to an audience of visitors and locals alike who were eager to have mementos of their encounters with the places featured in the novel.

Fig. 4. Adam Clark Vroman (American, 1856-1916), Chapel Where Ramona Was Married, Plate XXIII Interior of Chapel (Old Town), from A.C. Vroman and T.F. Barnes, The Genesis of the Story of Ramona. With Explanatory Text and Thirty Illustrations from Original Photographs, (Los Angeles: Press of Kinglsey-Barnes & Neuner Company, 1899), Courtesy of the HathiTrust

ILLUSTRATING RAMONA: THE PUBLISHER TAKES OVER

Although these first illustrated versions of the novel were produced by a small cadre of dedicated fans and entrepreneurs, including small scale publishers, it wasn’t long before Roberts Brothers recognized an opportunity to take advantage of Ramona‘s rapidly growing popularity. Its 1889 edition of the novel included an appendix by Edwards Roberts, “Ramona’s Home: A Visit to the Camulos Ranch, and to Scenes Described by ‘H.H.’.” The appendix simply reprinted Roberts’ 1886 San Francisco Chronicle article but also included four halftone illustrations of Rancho Camulos: The South Veranda, The Ranch-House, The Chapel, and The Old Bells.[52] Up to this point, the immense popularity of Jackson’s novel had led to repeated printings, in 1885, 1886, 1887, 1889, and again in 1899 by Little, Brown, & Co. of Boston, which had acquired the rights to publish it previous year.[53] The attempts on the part of Lummis, Vroman, and others to show the public the places that figured in Jackson’s story may well have influenced Little Brown in its decision to produce the first illustrated edition of Ramona in 1900, by which time 74,000 copies of the novel had been sold.[54]

The artist chosen for the task was Henry Sandham. He was born in Montreal in 1842, one of two sons to John and Elizabeth Tate Sandham.[55] Sandham’s father was a house painter, and both Henry and his brother worked in the family business. Eager to pursue an artistic career, however, he left home at the age of fourteen to work as an errand boy in the Montreal photography studio of William Notman. In 1860, when the studio added an art department, Sandham became an assistant in Notman’s studio to John Fraser. It was through Fraser and his acquaintances that Sandham began to study drawing, watercolor, and oil painting, one of the few practical ways of improving his skill in Montreal, which at that time did not have a formal art school. When Fraser left in 1868 to open a branch of the firm in Toronto, Sandham had progressed sufficiently to become head of the art department.

Sandham’s work began to receive official and public notice beginning in the 1860s. From 1865 on, his work was included in the annual shows of the Montreal Art Association, of the Society of Canadian Artists between 1868 and 1872, and in 1874 he began to show with the Ontario Society of Artists in Toronto. Four years later he won a silver medal at the Exposition Universelle in Paris for his large 1875 composite photograph, a specialty of the Notman firm.[56] By this time Sandham’s drawing skills brought him commissions from some of the more prominent literary magazines in the United States. He did illustrations for the August 1877 issue of Scribner’s Monthly as well as for his own article in the November 1878 issue. His career as an illustrator was boosted by being selected to do the drawings for Scribner’s four-part series by George Munro Grant, “The Dominion of Canada,” which appeared between May and August 1880. His reputation growing, Sandham was elected as a charter member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Art that same year. In April Sandham traveled to England and France, familiarizing himself with those countries’ art treasures, and in December he was in Boston to undertake a commission for a patron there. Apparently intent on establishing a career independent of his work for Notman, and perhaps encouraged by his success in illustration work for American magazines, Sandham decided to settle there, eventually ending his partnership with the Notman firm in 1882.

His arrival in Boston coincided with the decision in 1882 by one of his magazine patrons, Century (the successor to Scribner’s), to commission Helen Hunt Jackson to do her series of articles on California. Sandham was assigned to accompany her. The magazine’s articles were typically illustrated, often to enhance its many travel articles on sites throughout the world. The Jackson-Sandham collaboration was apparently well received by Century: eleven of his drawings were reproduced as illustrations to “Father Junipero and His Work. I,” fourteen for “Father Juniper and His Work. II,” thirteen for “The Present Condition of the Mission Indians in Southern California,” and ten for “Outdoor Industries in Southern California,” a total of forty-eight in all. Their subjects ranged widely according to the diverse topics Jackson explored in her articles. They included images based on his observations at missions San Antonio, San Gabriel, San Carlos Borromeo, San Miguel, San Luis Rey, Santa Barbara, San Juan Bautista, La Purísima, San Juan Capistrano, and Pala. There were also scenes from Indian villages at Pachunga and Rincon, and in the article on California industries were depictions of irrigation systems, sheep ranches, vineyards, orchards, and groves of eucalyptus and live oaks. To the casual reader of Century, they helped convey a sense of California’s past and the realities of the present that, according to Jackson, shaped the state’s particular social and economic character. Jackson’s popularity was such that her articles, with Sandham’s illustrations, were reprinted in book form in 1886 as Glimpses of Three Coasts, reissued by Roberts Brothers in 1891 and again in 1902 as Glimpses of California and the Missions by Little, Brown, & Co.

When it came time for Little, Brown, & Co. to publish its illustrated version of Ramona in 1900, however, Sandham faced a different challenge. Jackson had died in 1885 and the close collaboration he enjoyed with her on their work together for the Century articles was obviously no longer possible. Acknowledging the nature of his challenge in his “notes on Ramona Illustrations” in the 1900 edition of the novel, Sandham discussed his involvement with Jackson and how the illustrations evolved. “I was fortunate enough to travel in company with Mrs. Jackson at the time that she was accumulating the material for what has since become the best-known of all her books, and it was originally the plan that we should work together on it. Seventeen years, however, passed before I was able to finish my share of the work that Mrs. Jackson so graciously designated as ‘our book.’ At the time of the California sojourn I knew neither the name nor the exact details of the proposed book; but I did know that the general plan was a defense of the Mission Indians, together with a plea for the preservation of the Mission buildings, and so on…I thus had sufficient knowledge of the spirit of the text to work with keener zest upon the sketches for the illustrations; sketches, which, it may be of interest to know, were always made on the spot with Mrs. Jackson close at hand, suggesting emphasis to this object or prominence to that.”[57]

Sandham’s statement, however, contradicts in part what Jackson herself said about how her book came to be. The idea of a novel only came to her in October 1883, months after she returned from her second and final trip to California to research the Century articles, and there is no evidence to indicate that she and Sandham discussed any future plans for illustrating her novel. Nonetheless, Sandham was able to reuse drawings from a sketchbook he made on his earlier trips with Jackson.[58] From both the artist’s and the publisher’s perspective, this must have seemed valid in that so much of Jackson’s story was based on her California experiences prior to preparing the articles, which is precisely what Sandham sought to capture in his sketches. “The illustrations may, then, have this claim to a share of the reader’s attention: they, at least, faithfully represent the scenes and objects as they were actually seen by Mrs. Jackson at the time of the inception of the book,” he stated. Sandham went on to say, “There was no need to employ ‘artistic license’ in working up the sketches for publication, fact, in this particular instance being so much richer than fiction; and in this shaping and assorting of material gathered so long ago, I have merely tried to follow the path laid out by the author herself; which was to handle all detail in such manner as would best conduce to the artistic unison of the whole. As for the characters themselves, I have now in my possession sketches and studies made from the life at the time of my meeting with the originals, – a meeting that was often as much fraught with meaning for me as it was for Mrs. Jackson. All the dramatic incidents of the story were familiar to me long before I saw the book, as they are either literal descriptions of events which took place in the course of our travels, or they are recollections of anecdotes told when I, as well as Mrs. Jackson, was among the group of listeners.”[59] Discrepancies between Sandham’s and Jackson’s accounts aside, Sandham’s illustrations set the standard for Ramona for years to come.

1900: THE MONTEREY AND MONTEREY DELUXE EDITIONS

Little, Brown’s first illustrated Ramona consisted of two separate versions, the Monterey Edition and the more luxurious and expensive Monterey DeLuxe Edition, the latter of which was done in a run of 1500 individually numbered copies. Identical in size and each consisting of two volumes with a total of forty-nine illustrations, the two editions included an introduction by Jackson’s friend Susan Coolidge as well as Sandham’s “Notes on Ramona Illustrations.”[60]

The publisher promoted the release of this “A New Illustrated Edition of Helen Jackson’s Famous Romance of California,” advertising the regular edition as having “cloth wrappers, cloth box, with cover designs by Amy Sacker” for six dollars.[61] Sacker was a Boston-born designer who worked for several publishers there, including Little, Brown, and Company and Houghton Mifflin.[62] In her cover for the Monterey edition (Fig. 5), Jackson’s name and the rectangular border are impressed in gold, and an art nouveau floral design of green stems rising upward to a full spray of golden flowers at the top. The two-volume set came with a linen dust jacket the same color as the cover on which the title and author’s name were stamped in gold and on the spine, in the same typeface on both. The DeLuxe edition’s cover, as described in the same advertisement, was “three-quarters crushed Levant, gilt top” and was sold for twelve dollars. It was bound in either brown or dark green leather in an even more elaborate gilded art nouveau floral design stamped onto the sueded portion of the cover (Fig. 6).[63] Moreover, Little Brown advertised promoted these new editions by promoting “the superb pictures of Henry Sandham,” who according to the Boston Journal “has shown remarkable sympathy or insight to the text.” “Pictures (were) created under the guiding hand of the author herself,” Sandham wrote, and “give the finishing touch of reality to her words.”[64]

Fig. 5. Amy Sacker (American, 1872-1965), Cover of 1900 Monterey Edition of Ramona: A Story, Private Collection

Fig. 6. Amy Sacker (American, 1872-1965), Cover of 1900 Monterey DeLuxe Edition of Ramona: A Story, Private Collection

In these editions Sandham employed two distinct types of illustrations, all of which he identified by title and page in a list at the beginning of each volume. The largest and most impressive were the twenty-four full-page halftone illustrations,[65] each measuring 5-3/4 x 3-5/16 inches. Each illustration is protected by a thin, tipped-in cover sheet over which is another thin yellowish tipped-in sheet that mimicked the color of vellum. On this faux vellum cover sheet the illustration’s title, sometimes taken directly from characters’ dialogue, is printed in italics in a reddish-orange ink.[66] This design format calls the reader’s attention to the forthcoming illustration: first its title is given, sparking the reader to imagine how the scene will be depicted, and only after peeling back the two thin sheets of paper is the image itself revealed.

The key difference between the two Monterey editions is in how the full-page illustrations were printed. In the regular version, they were printed monochromatically in subtly different tints, alternating irregularly throughout the two volumes in pale shades of bluish-green, gray, sepia, brownish-orange sepia, and purplish grey. The subtle colorization of Sandham’s illustrations, then, provided a degree of luxury to the otherwise mundane world of black and white typically used for such reproductions.[67] In the DeLuxe edition most of the full-page illustrations were monochromatic, too, but the frontispiece in each volume was in full color as was one other illustration within the text. Although the halftone process, first developed commercially in the 1880s, enabled the reproduction of a range of tones present in the painted original, full color reproduction for the large runs found in book and magazine publishing was still in its infancy, and relatively expensive.[68]

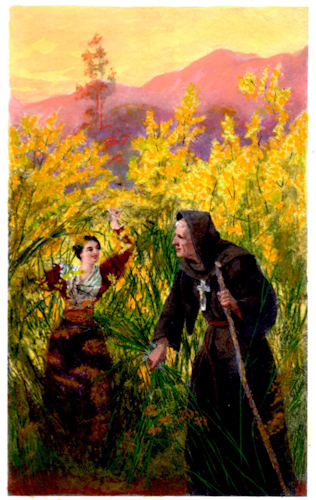

In both versions these full-page images typically show one or more of the characters from a key indoor or outdoor scene. This format is established at the very beginning in the book’s frontispiece, which shows the novel’s heroine meeting with her Franciscan missionary friend, Father Salvierderra (Fig. 7). They are surrounded on all sides by a thick growth of grasses and wild mustard flowers, Ramona’s face peering through them to look upon the venerable Franciscan. Sandham’s viewpoint is from slightly above the figures, enabling him to show the distant hills in the background and thus reinforcing the then-common view of southern California as an American paradise. This sentiment was frequently found in late-nineteenth-century popular literature in which this part of the state’s natural character was compared to Italy and even the Middle East.[69] Jackson herself emphasizes this notion, comparing the “wild mustard in Southern California” with “that spoken of in the New Testament.” This “yellow bloom” with “stems…so infinitesimally small, and of so dark a green,” in fact, is used in stylized form by Amy Sacker on the covers of both the Monterey and DeLuxe editions.

Fig. 7. Henry Sandham (Canadian, 1842-1910), Frontispiece to Volume I of the Monterey DeLuxe Edition, Ramona’s meeting with Father Salvierderra among the Mustard Blossoms, Private Collection

The fields of “wild mustard” must have appealed to Sandham – in June 1882, while on his trip with Jackson, he made a modest sized painting of the subject (Fig. 8). The foreground is dominated by the “yellow blooms” reaching more than halfway up into the composition, with the mountains in the background seen in shadows, further emphasizing the floral display. Pure landscapes are relatively rare among Sandham’s paintings, though his travels in his native Canada as well as Haiti and the Azores were the inspiration for them, in both oil and watercolor. It is doubtful he was planning to make oils on his trip with Jackson, as no others are known, and his choice of painting this work on a rough wood panel suggests it may have been a decision made on the spot, using whatever materials he could find. The subject’s precise location based on its 1882 is difficult to determine, as by that time Jackson had left for Monterey and San Francisco on her way to Oregon.[70] Between January and June, however, she and Sandham visited multiple Indian villages in the areas around the San Gabriel and San Jacinto Mountains, likely to have inspired Sandham’s oil painting. It seems to have had special meaning for both of them: it was among Jackson’s property at the time of her death and remains in her Colorado Springs home.[71] This romantic perception of California is reinforced by other Sandham illustrations that depict the state’s striking landscapes, one showing Salvierderra walking along the coast, another with Ramona and her companion Carmena standing on a pathway with gentle hills rising behind them, and one showing Ramona and her unsuccessful suitor Felipe meeting on the shore of a quiet lake (Fig. 9).[72]

Fig. 8. Henry Sandham (Canadian, 1842-1910), Field of Mustard, 1882, oil on board, Colorado Springs Pioneer Museum: Gift of William S. Jackson Family, 61.137

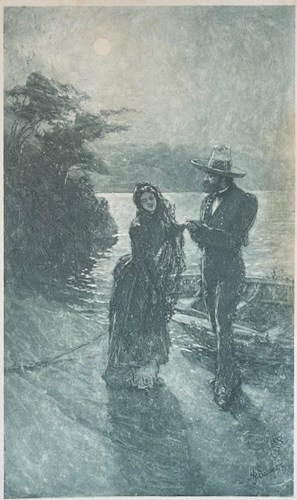

Fig. 9. Henry Sandham (Canadian, 1842-1910), Ramona my love! from Volume II, Chapter XXVI of the Monterey Edition, p.305, Collection of the author

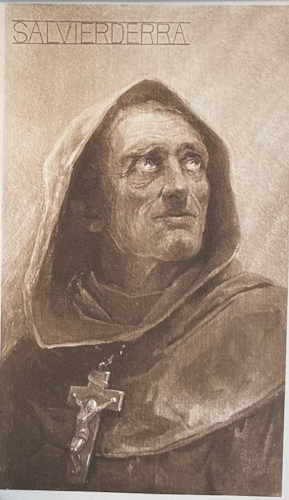

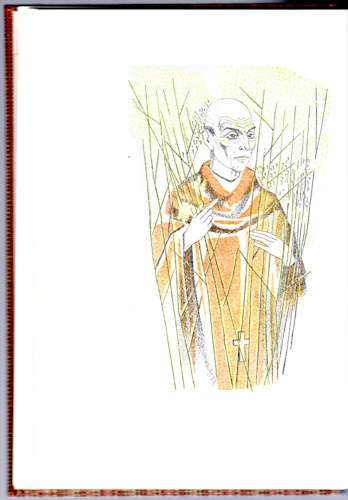

Salvierderra plays an important role in the novel, both as Ramona’s spiritual advisor and as a symbol of the Franciscan order’s role in Spain’s missionary enterprise in California. In that sense it is no surprise that he was the subject of a full-page portrait by Sandham (Fig. 10). Sandham’s rendering of Father Salvierderra unwittingly raises the question of how the novel’s main characters are depicted. At its heart, Ramona is about the tragic love affair between her, an orphaned daughter of an Indian mother and Scottish father, and Alessandro, Luiseño son of the chief of a band of Indians at Mission San Luis Rey. Underlying this narrative are fundamental issues of both race and gender, central to which is Ramona’s and Alessandro’s desire to marry. In no uncertain terms does her stepmother, Señora Moreno express her revulsion at the very idea, her sentiments made apparent even when she was first asked to adopt the infant Ramona: “If the child were pure Indian, I would like it better…I like not these crosses. It is the worst, and not the best of each, that remains.”[73] That the child would later want to marry an Indian was to Ramona’s stepmother even more distasteful.

Fig. 10. Henry Sandham (Canadian, 1842-1910), Father Salvierderra, from Volume II, Chapter XXV of the Monterey Edition, p.245, Private Collection

Yet racial prejudice is not limited only to colonialist views –American, Mexican, and Spanish – of Indigenous peoples. Moreno, the sister of the woman who was the ex-fiancé of Ramona’s father, is of Spanish heritage. She is the elderly and wealthy descendant of Spanish settlers who came to what was Spain’s viceroyalty of New Spain, living a half century after it gained its independence from Spain in 1821 and renamed itself Mexico.[74] From the novel’s very first chapter, Moreno is frequently portrayed as seeing the world around her in terms of race. She is described as “a sad, spiritual-minded old lady, amiable and indolent, like her race, but sweeter and more thoughtful than their wont” though her voice “heightened this mistaken impression.”[75] She was not alone in her view of southern California’s Native peoples by the state’s colonizers; to do the work of shearing sheep on her ranch, one of her Mexican ranch hands notices, disapprovingly, that “the Señora was determined to have none but Indians,” wondering, “under his breath, God knows why.”[76]

There is clearly a hierarchy, too, of class in which the landholding descendants of Spanish and New Spanish settlers and those who worked the land for them occupied very different positions in status and power. Essential to the novel’s plot is that this state of affairs, a legacy of the widespread inequities of Spain’s colonial enterprise, was under assault by Americans who resorted to whatever means necessary, legal or not, to take lands owned by both Mexicans and Indians alike. Americans are thus perceived by both as evil trespassers whose actions threatened their ways of life and, in Ramona’s and Alessandros’ case, their very lives.

How, then, do these matters of race and class within the colonial structures of late nineteenth-century California make themselves seen, literally, in Sandham’s and later other illustrators’ renderings of the novel’s characters? Sandham wrote in his “Notes On Illustrations” that his portrait of the Franciscan was “illustrative to the author’s fidelity to truth in character,” based as it was on “the original of Father Salvierderra. This character is positively startling in its accurateness. I knew the original Father well.” He noted, too, that “Though the Franciscans usually wear a broad-brimmed hat when in the open air, I never saw the original of Father Salvierderra wear a hat except when riding.”[77] The artist shows the Franciscan wearing his hooded robe with a large crucifix hanging from his neck, while his large eyes look skyward, presumably to God above. However fully Sandham’s portrait was based on the Franciscan he met during his travels in California, it nonetheless is tinged with sentimentality, an attempt to portray the padre’s spirituality that so often refers to him in the novel as “a Franciscan of the same type as Francis of Assisi.”[78]

Salvierderra is one of many members of the Franciscan order who came from throughout Europe and were sent to California beginning in the late eighteenth century as an integral part of Spain’s conquest of California. In terms commonly used in Jackson’s time to describe these Franciscan founders of the California missions, he appears in Sandham’s portrait the very image of the devout and heroic missionary sent to the New World to convert its Indigenous peoples to Catholicism, and in the process save their souls and turn them into “civilized” Spanish citizens.

This view of Spain’s missionary enterprise was held deeply by Señora Moreno, though with more than skepticism about its eventual prospects for success. In a conversation with her son, Felipe, who saw in the Indians who worked with Alessandro the same kind of loyalty and pride as his fellow Mexicans showed to him, she scornfully replied, “Of what is it that these noble lords of villages are so proud? Their ancestors, – naked savages less than a hundred years ago? Naked savages they themselves, too, to-day, if we had not come here to teach and civilize them. The race was never meant for anything but servants. That was all the Fathers ever expected to make of them, – good, faithful Catholics, and contented laborers in the fields.”[79]

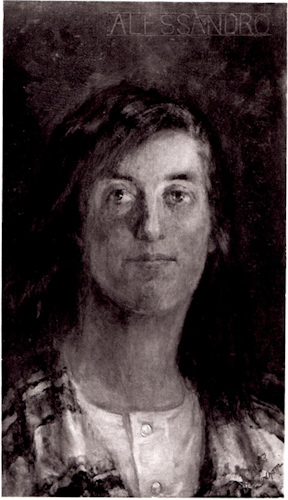

If Sandham’s portrayal of Father Salvierderra stands as a symbol of a heroic Franciscan missionary, his depictions of Alessandro and Ramona present something else. The novel’s text describes what Ramona looked like: “she had just enough of olive tint in her complexion to underlie and enrich her skin without it making it too swarthy…her hair was like her Indian mother’s, heavy and black, but her eyes were like her father’s, steel-blue. Only those who came very near to Ramona knew, however, that her eyes were blue, for the heavy black eyebrows and long black lashes so shaded and shadowed them that they looked black as night.”[80] Ramona’s features reveal the mixture of her Scottish father’s and her Indian mother’s lineages. Only her “steel-blue eyes” give away her whiteness, and only to those who come close to her. In fact, as Ramona scholar Jessy Randall notes, though she is able to pass as either Mexican or Indian, she cannot pass as white.[81] Sandham’s depiction (Fig. 11) is of a woman whose facial structure appears far more European than the then common stereotypes of Indians, and even acknowledging the limitations imposed by a monochromatic printing process, neither her hair nor her “heavy black eyebrows and long black lashes” are rendered as described in the text.[82]

Fig. 11. Henry Sandham (Canadian, 1842-1910), Ramona, from Vol. I, Chapter III of the Monterey Edition, p.42, Private Collection

Alessandro’s face is rendered in a way that even more minimizes if not erases his Luiseño heritage (Fig. 12). Insofar as Jackson’s text is concerned, only once is Alessandro’s physical appearance mentioned, by Ramona, and there only minimally. “For the first time, she looked at him with no thought of his being an Indian, – a thought there had surely been no need of her having, since his skin was not a shade darker than Felipe’s; but so strong was the race feeling, that never till that moment had she forgotten it.”[83] Ramona’s comparison of Alessandro’s skin color to that of Felipe, who himself was in love with Ramona, seems to express a kind of lessened racial difference, insofar as it is visible by their skin color. Felipe, of Spanish descent as was his mother, was likely born in Mexico, making any assumptions about his skin color from his lineage complicated at best given the wide racial diversity and mixture of peoples in New Spain.[84] The text seems to emphasize that Ramona had simply accepted Alessandro’s Indian features, less important to her than his kindness.

Fig. 12. Henry Sandham (Canadian, 1842-1910), Alessandro, from Volume I, Chapter XI of the Monterey Edition, p.224, Private Collection

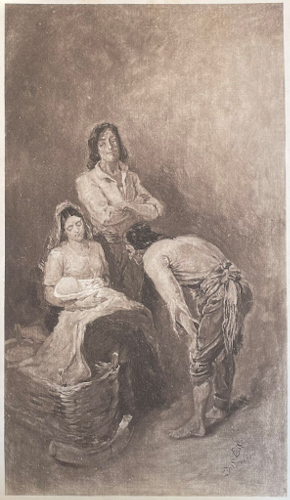

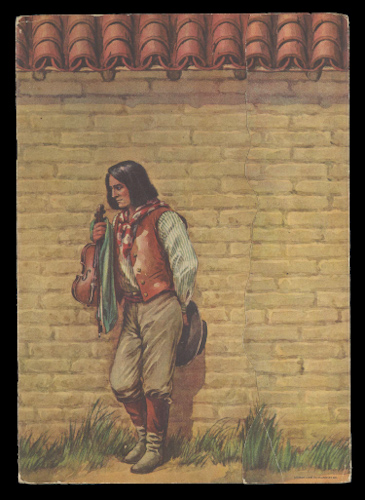

Another depiction of Alessandro appears later in the first chapter, as he sings by the bedside of Felipe, seriously ill with fever (Fig. 13). Violin at his side, he is wearing a light-colored shirt, his tie tucked partially into it, and plain pants and shoes, looking upward as he sings to soothe the sickened Felipe. There is virtually nothing about his appearance – clothes, style of his hair, or facial features – that suggest he is an Indian.

Fig. 13. Henry Sandham (Canadian, 1842-1910), Alessandro Singing to Felipe, from Volume I, Chapter VIII of the Monterey Edition, p.148, Private Collection

Sandham’s depiction of Ramona and Alessandro with their newborn daughter is an even more striking example of these erasures of race that permeate the novel’s illustrations (see Fig. 14). Once again, both of them bear few if any features that would have identified them to the reader as Indian. In this illustration, Ramona sits with their daughter in her lap as Alessandro stands next to her, while a male figure, likely Alessandro’s father, leans forward to get a closer look at his grandchild. The inclusion of the child’s swaddling clothes draped over the wattle cradle next to Ramona brings to mind countless versions of the birth of Christ, albeit in much simplified fashion, as the near-supplicant male figure at the right taking the place of one of the wise men come to see the Christ child. Though Sandham may well not have intended to suggest this association, it nonetheless takes on its appearance. And in the course of the narrative, Ramona’s and Alessandro’s child dies prematurely because the white doctor the couple found would treat the child of an Indian, a tragedy by any measure to the couple who embraced Christian beliefs.

Fig. 14. Henry Sandham (Canadian, 1842-1910), "'Eyes of the sky,' exclaimed Ysidro," from Vol. II of the Monterey DeLuxe Edition, p.129, Private Collection

What then may have driven Sandham’s decisions to depict as he did the novel’s two main characters whose Indianness is central to the story? His depictions seem not to have concerned the critics; on the contrary, a Boston Journal reviewer stated, “His heads of Ramona and Alessandro are truly ideal,” confirming perhaps how well Sandham’s conceptions met the expectations of Ramona’s largely white audience.[85] To some extent, Sandham may simply have been employing artistic conventions developed in a career as a painter and draftsmen in which he sought acceptance in the conservative academic circles of Montreal, Toronto, and Ottawa before coming to Boston. Yet he obviously encountered many Luiseños on his visits to several of their villages he and Jackson made during her research for her 1881 government report, A Century of Dishonor. He surely knew what they looked like, including whatever variations in their physical appearances they may have had.

A revealing comment easily overlooked in Susan Coolidge’s “Introduction” to the Monterey and Monterey DeLuxe editions of the novel suggests rather that it may have been Helen Hunt Jackson herself who influenced how Sandham depicted Ramona and Alessandro.[86] Coolidge’s introduction is essentially a succinct biography of the author, including the circumstances that led her to write the novel. When Jackson undertook her project in the winter of 1883-1884, Coolidge relates, “On her desk that winter stood an unframed photograph after Dante Rossetti, – two heads, a man’s and a woman’s set in a nimbus of cloud, with a strange, beautiful regard and meaning in their eyes. They were exactly her idea of what Ramona and Alessandro looked like, she said.” Though this photograph has not survived, we know that Jackson was an admirer of Rossetti’s poetry: Jackson owned four volumes of his work: Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s 1870 Poems and his 1881 Ballads and Sonnets, his sister Christina Georgiana Rossetti’s 1876 Poems, which included illustrations by her brother, and a copy of his other sister Maria Francesca Rossetti’s 1872 A Shadow of Dante. All of these volumes were published by Roberts Brothers.[87] It is through these volumes that Jackson knew Rossetti’s poetry and art.

It is difficult to know, however, whether Jackson’s appreciation for Rossetti’s works played any part in how Sandham depicted Ramona and Alessandro. There is no evidence of any communication between Coolidge and Sandham, though it is possible he may have seen her introduction in the course of preparing his illustrations. If that were the case, and even if he explored Rossetti’s work in considering how to portray either Ramona or Alessandro, his treatment of the two characters resembles only distantly the English artist’s work. While Sandham’s renditions of Ramona indeed do recall the English artist’s paintings of young, dark-haired and wistful English women who featured so prominently in his and his contemporaries’ paintings of medieval maidens and romantic heroines, Rossetti did few paintings featuring these maidens’ and heroines’ with their male counterparts.[88] Whatever may have led to Sandham’s decisions to depict Ramona and Alessandro as he did, what resulted were romanticized and deracinated images of both. What is striking about Jackson’s expressed ideals of how Ramona and Alessandro should look is that they ironically seem to stand in contrast to her stated and sincere wish to encourage her audience to seek fair and just treatment of the nation’s Indigenous people, a wish that would call for them to be shown as they really were.[89]

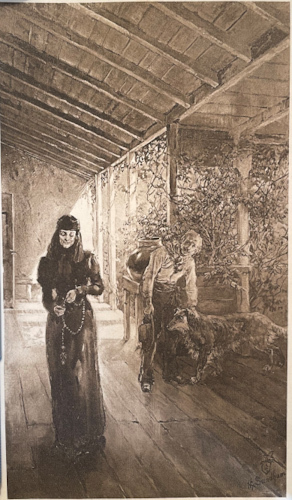

The rest of Sandham’s illustrations to Ramona do not give rise to the same kind of scrutiny as to their fidelity to the main thrust of Jackson’s novel. Rather, they instead provide an accurate visual backdrop of the many sites and activities that take place. An early illustration in first chapter of Volume I, for example, shows one of the novel’s villains, Señora Moreno, walking on the porch of what some readers would surely have identified as the south veranda of Rancho Camulos (Fig. 15). Entitled “Prayers, Always Prayers,” it shows the Señora walking on the veranda reciting the Rosary while one of her most trusted Mexican servants, Juan Canito, attempts to calm his favorite collie. Sandham faithfully captured the details of the veranda’s structure as seen in the many photographs of Rancho Camulos such as its planked floors and roof, the adobe walls that abut it, and the lush shrubbery that comes up to its edge. His rendition, in fact, is almost photographic, an effect perhaps encouraged by the halftone reproductive method but in any event making it effective competition to photographs of the sites seen in the earlier books by Lummis and Vroman. A number of scenes take place on the veranda, and Sandham depicts it from varying vantage points in three other illustrations, all based on a drawing he made at Rancho Camulos in 1882.[90]

Fig. 15. Henry Sandham (Canadian, 1842-1910), Prayers, Always Prayers, from Volume I, Chapter I of the Monterey Edition, p.9, Private Collection

Just as important is how the illustrations function in relation to the text. This one faces the page whose text describes the scene, relating Señora Moreno’s concern about her son Felipe’s illness and Juan Canito’s discomfort at relying on what he felt was the shepherd Luigo’s laziness in getting the Señora’s sheep back to the ranch in time for shearing them.

…he is no more fit to take responsibility of a flock, than one of the very lambs themselves. He’ll drive them off their feet one day, and starve them the next; and I’ve known him to forget to give them water. When he’s in his dreams, the Virgin only knows what he won’t do.

During this brief and almost unprecedented outburst of Juan’s the Señora’s countenance had been slowly growing stern. Juan had not seen it. His eyes had been turned away from her, looking down into the upturned eager face of his favorite colley, who was leaping and gamboling and barking at his feet.

“Down, Capitan, down!” he said in a fond tone, gently repulsing him; “thou makest such a noise the Señora can hear nothing but thy voice.”

“I heard only too distinctly, Juan Canito,” said the Señora, in a sweet but icy tone. “It is not well for one servant to backbite another. It gives me great grief to hear such words; and I hope when Father Salvierderra comes, next month, you will not forget to confess this sin of which you have been guilty in thus seeking to injure a fellow-being. If Señor Felipe listens to you, the poor boy Luigo will be case out homeless on the world some day; and what sort of deed would that be, Juan Canito, for one Christian to do to another? I fear the father will give you penance, when he hears what you have said.”

This close correspondence between the text and the accompanying illustration is a hallmark of Sandham’s concept for his illustrations and is found consistently throughout the book. The narrative on the left-hand page is given visual form by the illustration on the facing right-hand page, continually encouraging the reader to anticipate and then engage Sandham’s depictions of the story.

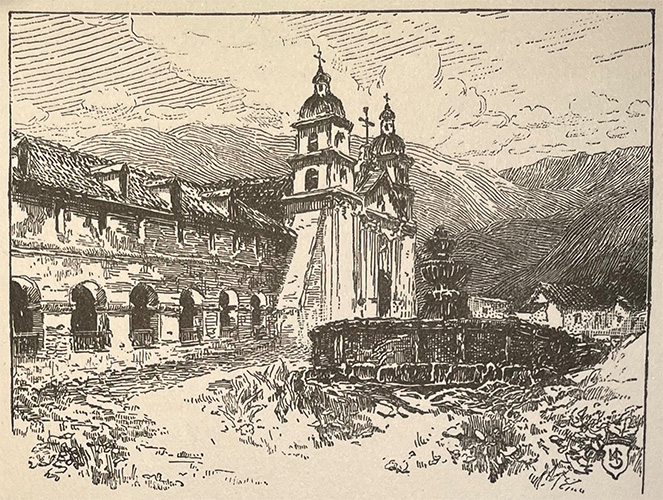

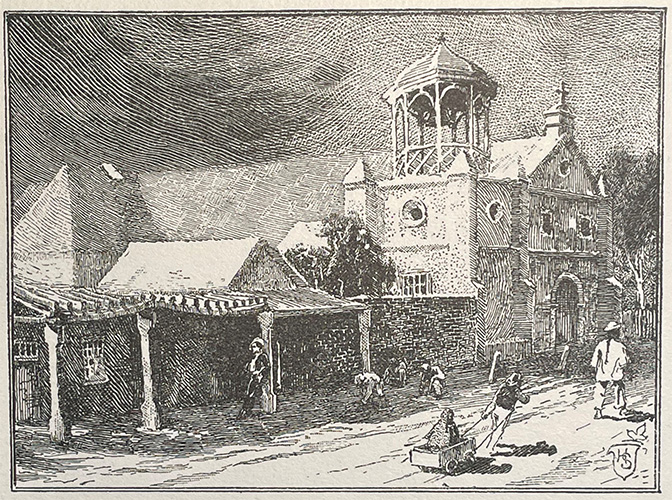

Another feature of Sandham’s illustration in the Monterey edition were the twenty-six “Decorative Headings” that appear at the very beginning of each chapter. Measuring approximately 2-5/8 x 3-3/8 inches, these nearly half-page images are also halftone reproductions which appear to have been made from etchings based on Sandham’s originals, presumably drawings in either pen and ink or pencil. Surrounded by a black border on three or four sides, they include Sandham’s monogram, a crest with a stylized oak leaf above that acknowledges his Canadian heritage, and Sandham’s initials in capital letters. These headings are almost exclusively views of various outdoor settings and interiors that, for the viewer, establish the locales where the story takes place.

Among them are views of missions Santa Barbara (Fig. 16) (Chapters II and VIII), San Carlos Borromeo (Chapter III), San Gabriel (Chapter IV), San Luis Rey (Chapters VI and XVI), San Juan Bautista (Chapter XV), Pala (Chapter XVIII), San Diego (Chapter XIX), and San Juan Capistrano (XXV). Six of the first eight chapter headings in Volume I and the four of the first five in Volume II, in fact, depict missions. Sandham thus reinforced the prominent role the missions play in the novel, prominent in part because of the events that take place at them, but perhaps more so because the Franciscans’ mission enterprise in Alta California established a range of historical, religious, social, and cultural underpinnings for many of the main characters and their actions.[91]

Fig. 16. Henry Sandham (Canadian, 1842-1910), Santa Barbara, from Volume I, Chapter II of the Monterey Edition, p.21, with Sandham’s monogram at lower right corner, Private Collection

Salvierderra was assigned to Mission Santa Barbara and it was there that Felipe met with him in an important scene at the end of the novel. Ramona’s father, who figures in the story only briefly in the very beginning, is said to have lived at San Gabriel, and Alessandro was raised by his family at San Luis Rey until the missions’ secularization forced their move to Temecula. Throughout the novel, scenes these and other scenes that place at the missions remind the reader of California’s mission heritage. As a Los Angeles Sunday Times critic noted, “Glimpses of the mission churches are here, ancient gateways under the palms which seem like the spiritual language of the crosses they overshadow.”[92]

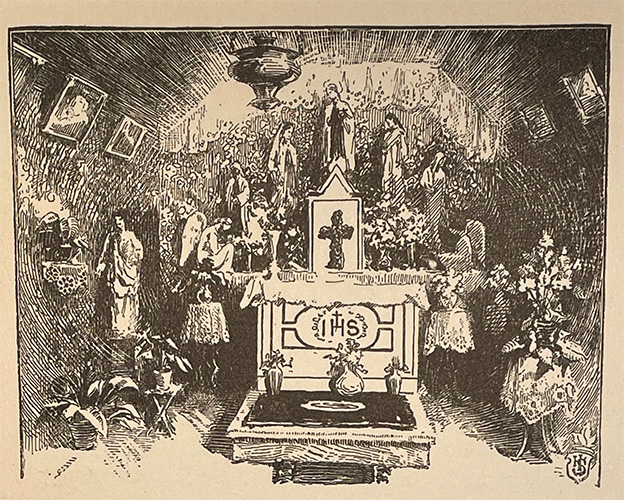

The novel’s second chapter, in fact, contains a brief history of the missions and their subsequent decline following secularization by Mexico in 1834.[93] Señora Moreno’s ranch, for example, is described as being on lands formerly part of missions San Fernando and Buenaventura (Volume I, 23). Secularization resulted in the rapid deterioration of most of the missions, and faithful parishioners sometimes appropriated religious objects to protect them from sale or theft in hopes of their being put to use in the missions’ churches at some point in the future. In the novel, the chairs and bench on the Señora Moreno’s veranda “had been brought to the Señora for safe keeping by the faithful old sacristan of San Luis Rey.” (Vol. I, 30). Similarly, “it had come about that no bedroom in the Señora’s house was without a picture or a statue of a saint or of the Madonna; and some had two; and in the little chapel in the garden the altar was surrounded by a really imposing row of holy and apostolic figures, which had looked down on the splendid ceremonies of the San Luis Rey Mission, in Father Peryi’s time.” (Vol. I, 30-31).[94] The importance of these multiple connections between the novel’s characters in the context of post-secularization mission history in the still young state of California are introduced early on in Sandham’s illustrations. The frontispiece to Volume I shows a meeting between Ramona and the Franciscan Father Salvierderra from Mission Santa Barbara, and the first Decorative Heading depicts the chapel at Camulos with all of its religious statuary (Fig. 17). The chapel, like the porch at the ranch, became one of the iconic images readers associated with the novel.

Fig. 17. Henry Sandham (Canadian, 1842-1910), Interior of Camulos Chapel, from Volume I, Chapter I of the Monterey Edition, p.3, Private Collection

For the most part, the missions are shown as uninhabited and in poor condition, reflecting the sad circumstances in which most of California’s missions had found themselves by 1900. Indeed, their dilapidated state was not only recognized but deplored by Jackson in her May and June 1883 Century articles, “Father Junipero and His Works.” There she commented on virtually all of the missions she and Sandham saw. “Many of them are still in operation as curacies; others are in ruins; of some not a trace is left, -- not even a stone.” San Diego had only its crumbling walls standing, at San Luis Rey “Piles of dirt and rubbish fill the space in front of the altar, and grass and weeds are growing in the corners’ great flocks of wild doves live in the roof, and have made the whole place unclean and foul-aired,” while “The most desolate ruin of all is that of La Purissima Mission…Nothing is left there but one long, low adobe building.”[95]

Jackson reserved her most searing condemnation for the condition of San Carlos Borromeo, which was Serra’s home church: “The roof of the church long ago fell in; its doors have stood open for years; and the fierce sea-gales have been sweeping in, piling sands until a great part of the floor is covered with solid earth on which every summer grasses and weeds grow high enough to be cut by sickles… It is a disgrace to both the Catholic Church and the State of California that this grand old ruin, with its sacred sepulchers, should be left to crumble away. If nothing is done to protect and save it, one short hundred years more will see it a shapeless, wind-swept mound of sand. It is not in our power to confer honor or bring dishonor on the illustrious dead. We ourselves, alone, are dishonored when we fail in reverence to them. The grave of Junipero Serra may be buried centuries deep, and its very place forgotten; yet his name will not perish, nor his fame suffer. But for the men of the country whose civilization he founded, and of the Church whose faith he so glorified, to permit his burial-place to sink into oblivion, is a shame indeed!”(Fig. 18).[96]

Fig. 18. Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916), Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, Monterey County, c.1883, silver print (15 1/4 x 21 3/8 inches), J. Paul Getty Museum: Gift in memory of Leona Naef Merrill and in honor of her sister, Gladys Porterfield, 94.XA.113.33

Señora Moreno, too, advocated for the missions’ restoration, and felt duty bound to return items from the missions placed in her trust “whenever the Missions should be restored, of which at that time all Catholics had good hope.” (Vol. I, 30). Sandham’s comment in his “Notes on Ramona Illustrations” at the beginning of the 1900 edition noted Jackson’s interest in preserving the missions and what the passage of time between his and Jackson’s trip and the publication of this edition had done to the missions. “The restorations of late years have materially altered the appearance of many places referred to in the story, a good example of such alteration being found in the heading of Chapter XIII (Fig. 19). Readers familiar with this Mission (Santa Clara) of late years only will remember the inside pillars of the corridor as neat and trim in a nice coat of plaster, one way doubtless of aiding in their preservation, but at the unhappy cost of utterly destroying that the feeling of picturesque ruin and age, the very quality that appealed most strongly to the poetic nature of the gifted author, and which really formed the basis of the inspiration of her work. The illustrations may, then, have this claim to a share of the reader’s attention: they, at least, faithfully represent the scenes and objects as they were actually seen by Mrs. Jackson at the time of the inception of the book, and before the hand of the preserver had destroyed their poetic value.”[97]

Fig. 19. Henry Sandham (Canadian, 1842-1910), Decorative heading with Our Lady Angels, Los Angeles (Mission Santa Clara) from Volume I, Chapter XIII of the Monterey Edition, p.260, Private Collection

Sandham’s comment reflects the growing concern about the missions’ condition. When he made it in 1900, there was already an organized effort underway to preserve the missions. In 1888, Reginald del Valle, then owner of Rancho Camulos, founded the Association for the Preservation of the Missions.[98] Four years later Tessa Kelso, the Los Angeles’ city librarian, formed a group to raise funds to save the state’s missions. When Kelso accepted a job back east in late 1893, she asked Charles Fletcher Lummis, who had helped del Valle found the earlier group, to take over the organization. Lummis enthusiastically agreed and by 1895, after securing the support of San Francisco Chronicle publisher Harrison Gray Otis and engineer Richard Egan, a director of the Santa Fe Railroad, Lummis incorporated the Landmarks Club. Using his magazine, Out West, to publicize this effort, making speeches, and even publishing a cookbook to help raise funds, over the next twenty years Lummis and the Landmarks Club eventually organized the restoration of San Juan Capistrano, San Diego, San Fernando, and Pala.[99] Sandham’s lament, then, seems to minimize the success of these various efforts to preserve and restore these relics of the Spanish missionary enterprise. Their perceived picturesque character and “poetic value” to which he refers had been noted by travelers to California since the 1820s, but it was evident by the end of the nineteenth century that their very survival was threatened, as Jackson herself had written in her Century articles.[100]

Sandham’s preference to show the missions in their “poetic” ruinous state, however, had a purpose in the story beyond simply being historically accurate to both the period in which the novel is set and the time of Jackson’s visits. With the exception of his illustration of Santa Clara in Chapter XIII, his images of the missions and even of Alessandro’s village at Temecula are almost entirely devoid of signs of human life. The loneliness Sandham depicts, which very likely was the conditions he and Jackson encountered on their visits, was also suggestive of the degree to which Ramona and Alessandro were themselves alone, striving and ultimately failing to find a way to live their lives together peacefully as husband and wife when their communities and cultures were under assault.

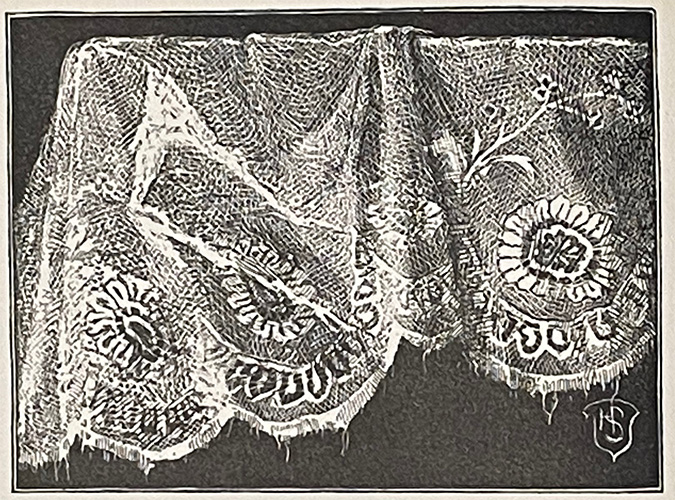

Sandham also included close-up views of various objects symbolic of key events in the story, such as a torn altar cloth that Ramona accidently tore and then secretly repaired so as not to sustain Señora Moreno’s wrath (Fig. 20). Another was the chest containing jewels and mementoes from Ramona’s father’s fiancé which the Señora kept hidden from her, as well as Indian-made baskets and lace. In each instance, these decorative headings typically set the stage for the events that take place in that chapter, predictive of the future rather than relating to actions in the present in contrast to those seen in the full-page illustrations. For Sandham, each type of illustration had its specific and consistent role to augment the text.

Fig. 20. Henry Sandham (Canadian, 1842-1910), Torn Altar Cloth, Camulus, from Volume I, Chapter V of the Monterey Edition, p.82, Private Collection

Despite the large number of subsequent editions and printings after the two Monterey editions of 1900, it would be more than thirty years before Ramona would again be so richly illustrated.[101] Nonetheless, there were other important visualizations of the novel in the 1910s. One of the most significant was the so-called “Tourist Edition” of 1913, also published by Little, Brown & Co. The version was nearly as elaborate in concept as the earlier Monterey editions. It included an introduction by Adam Clark Vroman, who in 1899 had published one of the earliest Ramona-related illustrated books, The Genesis of the Story of Ramona. The 1913 Tourist Edition of Ramona, however, was a new variation on previous models.[102] Copying the format of the 1900 Monterey edition, it included Sandham’s Decorative Headings at the beginning of each chapter, but to these Vroman added twenty-four full-page reproductions of photographs used in his 1899 Genesis book, focusing, of course, on the sites that Jackson visited that served as an inspiration for her narrative. Among them were eleven scenes of Camulos Ranch, five of Guajome, views of missions Santa Barbara, San Gabriel, and San Luis Rey, and one of the Indian village at Temecula. This reliance on images of the places associated with Ramona gave the edition a sense of authenticity no doubt appreciated by its readers.[103] In doing so this aptly named Tourist Edition could better compete with the many existing Ramona-related publications designed to appeal to the growing number of Ramona pilgrims to southern California. Even its cover (Fig. 21), based on Vroman’s frontispiece illustration for Volume I of the Moreno house at Camulos, was selected to compete for this audience.[104]

Fig. 21. Unknown designer, cover from 1913 Tourist Edition depicting Rancho Camulos, Private Collection

The strength of Vroman’s illustrations, of course, lay in their photographic fidelity to the well-known Ramona sites. One of the most intriguing is “Indian Houses at Temecula” (Fig. 22). It shows a small group of Indians from the village, standing or on horseback, before three typical tule-roofed dwellings. The ground around them is barren, and the scene’s emptiness a palpable reminder of the tragic situation in which Alessandro and his villagers found themselves as American settlers appropriated Indian lands in southern California.

Fig. 22. Adam Clark Vroman (American, 1856-1916), Indian House of Temecula, Plate XIX from 1913 Tourist Edition, p.238, Courtesy of HathiTrust

In terms of how the image serves to complement the novel’s text, however, its context differs significantly from that in the 1900 Monterey edition. Like all the halftone reproductions of Vroman’s photographs that appear in the Tourist Edition, each image was covered with a tipped-in sheet bearing a printed title, text or texts relating to the scene depicted, and the page and volume number for the text(s). This format is much the same as found in the 1900 edition: the reader would first come upon the tipped-in sheet with title and text on the left-hand page and then lift it up to reveal the illustration located on the adjacent right-hand page.[105]

In contrast to the 1900 edition, however, where the full-page illustrations are directly related to events described on the pages directly adjacent, Vroman’s are not so closely aligned with the relevant text. His thirteen plates in Volume I, twenty-six pages apart from each other, begin on page four,[106] and are accompanied by eighteen selections from Jackson’s text.[107] Twelve of these selections, however, refer to passages on pages twenty-two to thirty. This concentration of text references within these early pages of the novel is understandable, as it is in these early chapters that Jackson describes the Moreno ranch that is the subject of so many of Vroman’s illustrations to Volume I. This disjuncture between text and image, however, is even more exaggerated in Volume II. There, of the nineteen quotes on its eleven plates, eleven refer to texts in Volume I. The quotes for Volume II are even more distant from the corresponding parts of the narrative; the text accompanying Vroman’s image of Temecula actually appears more than one hundred and eighty pages earlier than the plate.[108]

This disjuncture was made unavoidable by the decision to employ Vroman’s photographs of Ramona sites for the novel’s main illustrations. They depict real places rather than an illustrator’s creative interpretations of dramatic events in the novel. Their value was due to photographs’ implied verisimilitude, rendering fact rather than fiction, thus resulting in a fundamentally different relationship between image and text in this otherwise strikingly and richly illustrated version of Ramona.

BRINGING RAMONA TO THE BIG SCREEN

At the same time these variations upon the 1900 Sandham-illustrated editions of Ramona were released, the novel found expression in another, arguably more dynamic medium that would alter the public’s visual conception of Jackson’s novel for decades. In 1910 D.W. Griffith made the first Ramona film. He was already familiar with Jackson’s novel, having played the role of Alessandro – twice – in Virginia Calhoun’s 1905 theatrical version of the novel.[109] As he prepared to take his company to California for the first time in 1910, he pressed the American Biograph Company to acquire the rights to the novel from Little, Brown, and Company.[110] Just two years before, a U.S. Supreme Court decision required filmmakers to pay authors for the rights to make movies from their novels, and Biograph thus paid Little, Brown & Co. $100 to do so, the highest price yet paid for such rights.[111] Seeing the film’s potential, Biograph issued a special handbill to promote its production.

For Griffith, it was the most ambitious of his films to date cinematically by including forty-five scenes photographed from twenty-two camera positions. In addition, there were eighteen subtitles, more than in any of his previous films, necessary in that these subtitles, which immediately preceded the scenes, helped explain the narrative. Jackson’s book, after all, was more than four hundred pages long with twenty-six chapters and reducing it to the 1000-foot film length limit imposed by Biograph presented a significant challenge. Perhaps for that reason, the film was given a more explanatory title, Ramona: A Story of the White Man’s Injustice to the Indian.

Griffith sought to make the film adhere as closely as possible to what was, after all, a story well-known to his likely audience. The credit noted not only that it was “Adapted from the novel of Helen Jackson by arrangement with Little, Brown & Company,” but that “This production was taken at Camulos, Ventura Country, California, the actual scenes where Mrs. Jackson placed her characters in the story.” In this regard, he was surely seeking to take advantage of the degree to which places associated with Ramona in Jackson’s novel had become pilgrimage sites for the devoted, and he did not disappoint. His shots at Rancho Camulos of the veranda, chapel, and mission bells and trellis would have been immediately recognizable to those familiar with either the illustrated versions of Ramona or Vroman’s 1899 book, as well as to those thousands who actually visited the site.