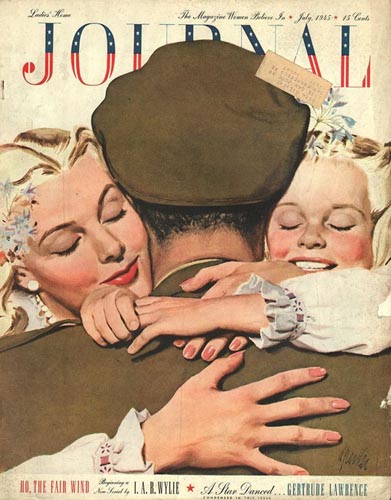

Fig. 1. Alfred Charles Parker, Cover of Ladies’ Home Journal (Mother and Daughter Welcome Returning Soldier), July 1945. Al Parker Collection, Department of Special Collections, Washington University Libraries.

The longing for normalcy that fills any people engaged in a conflict such as one so costly as World War II presumes that, with the end of fighting and the return of the warriors, things can somehow go back to the way they had been before the shooting began. But for Americans in 1945, following after not only four years of war but also the Great Depression, which was a decade old when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, whatever had been “normal” for parents and grandparents was gone beyond recall. For this generation, far removed by both time and dramatic change from the pre-depression twenties, the very notion of everyday life awaited redefinition. Emerging from a long, dark period of extraordinary circumstances and profound political and economic transformation that, given the extreme demands of mere survival had largely gone unrecognized, Americans had little idea in 1945 what “normal” and “everyday” might mean in their own time.

Al Parker’s post-war illustrations, while continuing to appear in the same magazines that published them before 1941 and expanding on themes already introduced in that early work, provide a remarkable insight into how in the America of 1945 he and his countrymen were re-imagining themselves and the new lives they were hoping to begin. Production, finely tuned by wartime necessity, turned in peacetime to new products and consumers. What had been denied in years of want and insecurity became abundantly available and now, rather than marketed as luxuries for the few promoted as essential to everyone. Single family homes in the suburbs filled with modern appliances, new cars, new amusements, and conveniences of a startling variety were being offered as the substance of a new “normalcy” and the better life to which military success and peacetime entitled us.

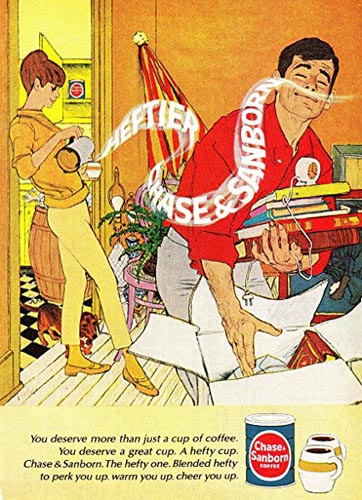

Fig. 2. Alfred Charles Parker, Chase & Sanborn coffee advertisement, 1968. Al Parker Collection, Department of Special Collections, Washington University Libraries.

So it was that Al Parker, while illustrating magazine stories, was depicting a dramatic cultural transition as well, not only picturing new products for advertisers but also a new lifestyle. He was showing his countrymen who we were or, to be more precise, who we imagined we could be. What copy such as this for Chase and Sanborn declared—“You deserve more than a cup of coffee. You deserve a great cup. A hefty cup.”—Parker interpreted, giving a face and personality to the “you” together with a home and family in which Chase and Sanborn’s brew was only one of many constituent parts. His pictures created a context for washing machines and cars and telephones, a larger rationale for the things that Americans were being sold, and he visualized a way of life in which these products both made sense and contributed to a stronger conviction of well-being. There is in all of his work, along with the straightforwardness required by advertising, a wry and ironic sensibility and, most importantly, a special pleasure in transgressing boundaries of every sort. It is this last characteristic that allows him to represent the post-war ethos, to elaborate a cultural phenomenon in which any usable past was too far removed to rejoin.

In this regard Parker was often well matched to the wares he promoted, a point perhaps most apparent in the several American Airlines advertisements featuring his art. Limited to the rich before the war, air travel by the 1950s was being promoted more broadly as a travel alternative, with carriers insisting in mass-market venues that much that had in the 1920s been “far removed” was now amazingly close at hand. “Mountains or beaches?” a 1952 advertisement asks before adding the new option, “or both?” “Spring never leaves Acapulco,” another reports, and in yet another, individuals freshly delivered from northern travail shrug off coats to join friends on beaches or boats. In scene after scene, an enticing leisure life that prior to the 1950s had belonged exclusively to the wealthy was suddenly presented as a middle-class prerogative. What gave that astonishing claim credibility was neither economic data nor sociological analysis but Al Parker’s pictures, images in which “ordinary” Americans appear in exotic settings and indulge in forms of relaxation that would have surprised—if not shocked—their parents, and look for all the world as though they are unaware that anything unusual is taking place.

Central to Parker’s genius was his ability to blur the lines between ordinary and extraordinary, to cross a social and cultural boundary that had been carefully maintained and policed in the pre-World War II world. He accomplished this transgression by emphasizing choice over class and treating the latter as largely a matter of costume and posture. In an era when the preferred evening dress of old money could be obtained on an hourly basis (thanks to a new tuxedo rental industry) or when high-fashion knock-offs could be purchased off the rack in department stores, sophistication hinged on the ability to look at ease, even detached, rather than on pedigree. In one American Airlines advertisement, a man in a light grey jacket and pants chats with two attentive and beautiful young women. Smoking, drinking, and chatting, they appear to be in a luxury liner’s salon car rather than on a plane. There is no display of the white-knuckle concern of inexperienced travelers, and certainly no insecurity about belonging in either this setting or company. Signals of class are both pronounced and ambiguous; the women are elegantly dressed, one with a fur collar and gloves, and the stewardess is carrying away a mink coat, but the ad is addressed to “experienced travelers,” implying an urbanity that is the consequence of experience rather than of birth or wealth. Of the male figure little can be said other than that he is clearly comfortable, confident, and sure of himself in a way that only privilege or experience can explain. Unlike his fur-bearing companions, he shows no particular evidence of affluence, his dress only tasteful and his manner confident. But for an America “experienced” in economic depression and world war, taste and confidence counted for more than old presumptions, and an easy manner was more important than high social connection. The man on this transcontinental flight, most likely a business traveler, represents the audience American Airlines was aggressively pursuing. In this brave new world in which geographical distance has been conquered by jet travel, so has the gap between the middle and upper classes been narrowed, at least in claims to worldliness and sophistication.

In the 1930s, Parker (and the writers he was illustrating) tended to exoticize class, to titillate readers with the opportunity to spy, unobserved across the boundaries that were so starkly drawn in depressed America between affluent society and everyone else. As in fan magazine accounts of movie star life, popular interest in high society depends upon the distance that divides the audience from the subject and the unbridgeable nature of that divide. A December 1933 Ladies' Home Journal piece entitled, “Sheathe Yourself in Glamour and Elegance for Evening,” for example, is superimposed over a scene—appropriate to a Noel Coward stage set—of tuxedoed men and sleekly “sheathed” women slouched on chaise lounges, clearly free from the worries of ordinary life and bored of their own small talk. The fact that by the late 1940s Parker could be using quite similar costumes and postures for more ordinary Americans, though largely without the implied ennui, suggests a remarkable transition. In his drawings, this change seems directly linked to the most dramatic revision in America’s dress code—the inclusion of men in military uniform. Apart from the implications of rank (when it can be determined), service dress concealed class and suggested a level of experience that became the foundation of post-war notions of sophistication. In an April 1945 Ladies' Home Journal illustration, a man in dress greens, hair oiled and combed in the same fashion as the tuxedoed males of 1933, leans one elbow on an ornate fireplace, the opposite arm bent with hand on hip, and watches bemused as a female figure who nearly obscures him tilts back, eyes closed, to smell a bouquet. Her dress is an updated version of the silk sheathes that, twelve years earlier, promised both glamour and elegance. Her lithe fashion model stance as she curves herself, impossibly, into the moment, updates the older model of sophistication, but with a much greater physical presence. The posturing here involves a self-awareness missing from the earlier picture, part of a performance not of boredom but of seduction, a game that the uniformed man’s slightly bemused, slightly impatient look acknowledges.

Physicality of a sort missing in the earlier drawing, the clear sense of a man and a woman as opposed to a drawing room group, was an essential part of Parker’s appeal to post-war readers. This, too, reduced the importance of class, suggesting the greater significance of attraction and desire. When the same uniform reappeared in the July 1945 issue of Ladies' Home Journal, it is back and center as the returning veteran is embraced by the famous blond mother and daughter so familiar to Ladies' Home Journal readers. The back of the soldier’s head and shoulders are all that can be seen of him as he cradles his wife’s head on one shoulder and his daughter’s on the other. Like the glamorously styled woman in the May issue, the females in this illustration are impeccably dressed and made up, and like their predecessor they both come with flowers and demurely closed eyes. But this is a domestic moment rather than one of seductive posturing, and the man in the uniform is a classless American, one remade by his uniform and the experience it implies.

Al Parker’s mother-daughter covers, including those from before the war, confused issues of class in much the same way as did 1950s television portrayals of the American family. His women—suburban and urbane, glamorous and representative— embodied an anticipated rather than a recalled or realized United States, and represented a new kind of relationship between generations as well as sexes. Where other illustrators looked back to an idealized past for their cultural moorings, Parker looked to the future, choosing reinvention over recovery in his representation of post-war aspiration. In this version of our national story we were more defined by what we were about to become than by what we had been. The modern was embraced and progress assumed. Transformed by the profound disruption of depression and war, and all the better for the change, Americans were freed to take greater liberties, to express themselves more fully. A sort of middle-class classlessness was the imagined foundation for a new society, a culture being rebuilt by the likes of Levitt on the former potato fields of Long Island and the equivalent farmland surrounding every major metropolitan center. If the reality was nearly always shabbier than advertised, popular commitment to this path of reconstruction rarely wavered. New appliances, a second car, and do-it-yourself improvements would salvage the brighter future even from the betrayals of profiteering developers and corrupt politicians. On television, General Electric’s Betty Furness virtually waltzed around her kitchen in cocktail dress, heels, and pearls, her housework apparently made effortless by the bright new appliances she was hawking. Harriet Nelson and June Cleaver, similarly attired, oversaw traditional families and ordinary husbands and lived lives that seemed familiar enough even if their clothing and unfailing cheerfulness were not. In these portrayals of American life, the ordinary and the exotic were effortlessly combined, the reality of everyday life—cooking, cleaning, mischievous children, slightly bumbling husbands—were mixed with elegance and luxuries associated a generation earlier with great wealth. What had once required servants could now be provided by mechanical devices, machines either within reach of the middle class or close enough to seem attainable after the next promotion.

Fig. 3. Alfred Charles Parker, Cover illustration for Ladies’ Home Journal (Mother and Daughter Skiers), March 1942. Collection of Kit and Donna Parker.

The redundant grace and apparent contentment of Parker’s homemakers, especially the women depicted on the Ladies' Home Journal covers who seem to enjoy both family and an abundance of leisure time, surely contradicted the experience of the magazine readers for whom they were intended, and yet they remained popular by aspiration. Somehow Americans imagined this was the way things could be, the way they should be—glamour and housework reconciled, children and personal development made compatible, marriage and romance combined. The new mother could be as stylish as a socialite and still dispense homely wisdom, and added to her femininity was an athleticism more sexually charged—at least for Parker’s generation—than the elaborate postures of an earlier sophistication. The new family (as in the 1950 American Airlines ad in which the businessman husband returns to an elegantly attired wife and loving children), properly housed and costumed, became a more glamorous subject than high society soirees, the suburban mother as elegant as the fashion model whose dress she seems to have adopted, upper-class ennui less interesting than the middle-class excitement of achieving and consuming.

The foundation of this idealized America appears to have been cleanliness. Parker’s mother and daughter subjects were not only blond but also much inclined to wear white, and they were always (with the exception of a wartime stint as auto mechanics) spotlessly, breathtakingly clean. In a 1943 story cover, his blond female subject is exiting a vehicle, stepping down into a muddy rural road despite her white shoes and frock, but she is frozen in the moment before she is dirtied by the mire. Her male companion, leans out the truck door sufficiently far that we can see that his white shoes and slacks remain immaculate. The tension of the picture seems as much invested in the confrontation between all that purity and all that mud as with whatever is going on between the separating figures. For obvious reasons Parker seemed to prefer sand—or even ice—to mud for his outdoor scenes and used that whiteness to ground his characters in an unsullying world.

Dirt, albeit of a sanitized sort, is appropriate to nostalgia, the smudged faces of the children we used to be, the work-begrimed figures of the farmer or the village smith, but the future we are inclined to imagine is clean, scrubbed of toil and anxiety as well as mud. Utopias are without fail very tidy places. Looking back, it is easy to attribute much of 1950s longing as a response to nearly fifteen years of war and deprivation. The heavily advertised detergents, toothpastes, body soaps, dishwashing liquids, mouthwashes, deodorants, and all of those washers and driers and vacuum sweepers that drove the American economy almost as far as did the automobile, were surely part of a campaign to scrub away those years of unhappiness and insecurity.

But just as important was a sense of what social progress demanded. The more disturbing post-war conditions—childhood diseases like polio, persistent poverty, racism, political witch-hunts—were also cold war realities, not just lingering disruptions from a cruder past, and without fail they also engaged a vocabulary of “cleaning up.” Our first line of defense against disease or profanity (as every mother and advertising firm knew) was soap and water; the badge of justified poverty was dirtiness, and those families identified as the “deserving poor” bought their first concessions by being well scrubbed even if also patched; bigotry was widely regarded as our national dirty linen either to be laundered or, the more popular solution, swept under the rug; and J. Edgar Hoover, himself impeccably tidy and freshly laundered, liked to imagine the FBI as a national cleansing company, “cleaning up and clearing out” all our social and political contaminations.

Fig. 4. Alfred Charles Parker, Cover of Ladies’ Home Journal, October 1948

Popular art, whether literature or movies or magazine illustration, was divided between works exploring the inherent messiness of America in the post-war era and those who cleaned things up. If Joanne Woodward won the Academy Award for Three Faces of Eve, Doris Day with her pristine romantic romps was queen of the box office; Grace Metallius portrayed a very different version of the family than did Ozzie and Harriet; and the wifely experience gracing the cover of Ladies' Home Journal would in the early 1960s be challenged by Betty Freidan. Exposure and illusion were equally marketable. Whatever the Kinsey Report had to say in its hundreds of pages, Hugh Hefner offered a formula designed to simplify it all. However compromising and self-annihilating espionage might be portrayed as by Graham Greene or, later, John LeCarre, Ian Fleming made the game easy and fun.

Not surprising since he was both illustrating and creating a popular culture, there is much that Al Parker seems to share with Playboy and James Bond. Masculine sophistication was a preoccupation of all three, sometimes (at least with the Bond novels and the Parker images) with tongue at least reaching for the cheek, but always rooted in a ‘50s and ‘60s version of cool. Playboy’s rise was due to its ability to combine a skin magazine’s titillating vulgarity with an aggressively marketed image of urbanity, an effort to relocate pictures associated with garage calendars and the underside of mattresses in adolescent male bedrooms to the penthouse or the mansion. Marketing “sophistication,” providing the appearance of experience to precisely those who lacked it, became a major function of men’s magazines. In much the same way that women’s magazines advised their readers through the transition into the suburbs and middle-class, books and magazines written for a male audience found steady business in post-war America advising insecure men. A crucial difference was that while the family, motherhood, and home maintenance were central to the articles in Ladies' Home Journal, no comparable emphasis on fatherhood or husbandhood is evident in Playboy. The market for “cool,” combined with pictures of naked women, filled the pages of the new men’s magazines with advice on clothes, apartment furnishings, music, and wine—virtually everything a middle-class bachelor might need in order to impress the “girls” he could bed without commitment.

Ironically, the sophistication newer men’s publications were promoting often bore a resemblance to the post-war culture Al Parker had begun portraying even before the war ended. If the high fashion once reserved for celebrities and high society appeared on both mother and daughter in his most celebrated pictures, so did its masculine equivalent replace the military uniform of his early forties illustrations. Well-tailored men joined their female partners in Parker’s promiscuous mix of class and condition. However, while Playboy pretended that its readers did not marry or have children, Parker celebrated a kind of “cool” that was not so restrictive. The enthusiasm for cocktail parties and supper-clubs so strong in the '50s and '60s existed side by side with the sleek kitchen appliances and family vacations in his version of the new American culture, the version not surprisingly embraced by women’s magazines. The peculiar seriousness of Playboy in its pursuit of a more discriminating (one of that magazine’s favorite words) reader nicely illustrates, by contrast, a persistent playfulness in the Parker illustrations. If his mothers get to be glamorous, it is, often as not, in a fashion connection to their children, and the attractive woman on the arm of a man-about-town may very well be his wife. Having devoted so much of his career portraying a fantasy that was in many ways masculine in publications intended for women, he developed a subtlety and humor mostly absent from the men’s magazines.

It is striking how consistently Parker’s art both anticipated and then illuminated the post-war conception of a new America and a new American. He, and the magazines that employed him, realized that the returning GIs and their necessarily self-sufficient wives had a unique opportunity to shed old identities and challenge traditional stereotypes. Taking off their uniforms—whether military order or occupational—men and women could choose what they would put on next. If the workplace was being returned to male employees, women were neither willing nor able (given the housing shortage) to return to the homes in which their mothers worked. Levittown and similar developments offered affordable housing designed around appliances unavailable before depression and war. If mothers were recharged with old duties, the performance of those chores promised to involve a technology never before available. Clothes were to be washed in neatly contained boxes, notably missing the wringer, and subdivisions increasingly frowned even upon clotheslines as tacky and inappropriate for progressive homeowners. The marvelous kitchens that defined the new American home were, thanks to electricity and natural gas, clean burning, and dry cooling, and labor saving. And at the end of the day, middle-class men who labored at white collar jobs eagerly returned home, tired but free of grime, to wife and children. All of this Parker’s illustrations promoted and celebrated, a convenience-filled life with more time—time for vacations and family outings, time as he shows us for coffee and fly tying, time for reading and music, cocktail parties, and nights on the town.

In short, Parker’s Americans are people with greater personal freedom and more choices than any of their predecessors had enjoyed. They are athletic and youthful, ironically unchanged by domesticity. In his world, women who have given up their wartime jobs for more traditional homemaking do not surrender the physical activities of their youth, but rather share them with their daughters. His mothers and daughters skate and ski and swim as well as sew and bake. Similarly they do not, simply because of marriage, cease to be objects of desire, but are allowed to combine the domestic with the romantic. These people, women as well as men, are blatantly physical, even sexual in a manner similar to yet also quite different from that of the bachelors and bunnies in Playboy or the men and women of Ian Fleming intrigue. Whereas the desires depicted in these latter publications seem perpetually restless and impossible to satisfy, reasserting themselves unchanged in issue after issue and book after book, Parker’s men and women convey an aura of well-being, of contentment. The presentation of intimacy developed in his mother-daughter covers for Ladies' Home Journal expands and intensifies over time, enriched rather than undermined by commitment.

Of course Parker presented an image of American life that was idealized, that let us have our cake and eat it too, a fact he often acknowledged with ironic wit (consider his comic sequence in which a man is trying—with masculine efficiency—to do the housekeeping), but that image reflects an aspiration that is in many ways admirable. While it transgresses many social boundaries, it does so in a way that attempts to reconcile rather than antagonize. If he does not depict the actual households in which most baby-boomers grew up, his version is nevertheless one that expands rather than constricts, that recognizes and applauds the aspirations of women as well as men, and that tries to imagine a family that is happy rather than merely submissive—a family that actually enjoys itself.

Fig. 5. Alfred Charles Parker, Stevie, 1956. Story illustration for McCall’s, January 19, 1956, Al Parker Collection, Department of Special Collections, Washington University Libraries

In one of the most compelling of Parker’s paintings, done for McCall’s in 1956, a child peeks through a sort of visual crack in the canvas. Amidst all of that white, she peers out at the world in which we live, the reality beyond the page. A Christmas cover similar in layout but done twelve years earlier—part of the Ladies' Home Journal’s 1944 mother-daughter series—features the familiar look-alikes in matching outfits opening the picture like a stage curtain. They are anticipating, a note from the child informs us, that “Daddy … will be home pretty soon now.” The effect is hopeful, dominated by a Christmas pattern on both the surrounding space and their apparel. The women represent what the father is fighting for, and his return is the promise of restoration and wholeness. In none of these wartime images is the father needed for his competence, but rather is missed for himself. It is his presence they await rather than a better way to make ends meet. In this picture, the connections between mother and daughter—a shared beauty, an obvious pleasure in each other’s company as well as the redundant dress—provide the reassurance that family is supposed to give. But the child in the later picture seems more on her own, challenged to make sense of whatever is out here where we readers live, a world both cluttered and empty, both shaped and waiting to be made. It is this wonderful moment in which the picture requires us to imagine what she sees as she peers out at us and, in that leap, to reconsider what we imagine ourselves to be. We recognize an exciting and terrifying challenge in her situation and in it a powerful evocation of the one that faced Americans at the end of war and in the years that followed, one full of risks and possibilities. In this picture Parker, who has so broadly described what that world might contain, allows us to see ourselves, looking childlike into a life that we are always simultaneously already in and about to enter.