Andy Warhol and Norman Rockwell together under one roof—how amazing is this? To many it might appear to be the art world’s version of “The Odd Couple,” but to me it makes perfect sense. Then again, I am an illustrator who ranks both artists high on my list of heroes, and perhaps I cannot help but be biased since I am nephew to Andy Warhol, whom I still refer to as my “Uncle Andy.” Some may surmise that Rockwell and Warhol have little in common and it’s probably true—but as image-makers of the 20th century, they are two powerhouses. I am thrilled to write a few thoughts about how I relate to them for Inventing America: Rockwell and Warhol, as both had an influence in my decision to become an illustrator. Of course, I’ll have more to say about Uncle Andy, as I was running around at his feet when he was illustrating shoes and painting soup cans.

In discussing the work of Rockwell and Warhol, I can’t help but start off with the question often asked me—artist, illustrator, or both? There has always been a running conflict regarding these two livelihoods. Some illustrators don't feel any affection toward modern art while some artists are of the opinion that the field of illustration is below their domain. This snobbery of artist and illustrator isn’t just among ourselves; it also extends to art collectors, art directors, art critics, historians, gallerists, and whoever else wants to get into the fray. The conflict will always be around, but in the context of this show it is especially evident. Rockwell was proudly an illustrator and perhaps less interested in the “artist” label, but many will agree he was as fine an artist as ever will be. My uncle, though known as an artist, was always very proud of his work as an illustrator. To me he was indifferent to the subject. He would say “it’s all the same,” which I took to mean that it’s all about creating imagery, so why differentiate? After my uncle was well recognized as a Pop artist, he was still excited by the opportunity to illustrate covers for magazines like Time and TV Guide, and the numerous record album jacket designs requested of him. Many artists would never have gone near such commercial work, but Andy did, with pride. Rockwell and Warhol under one roof is a great opportunity to think about the dual professions of commercial illustration and fine art, their purpose and function, and how they may overlap.

When I first became aware of Uncle Andy, he was already an eccentric uncle living with my grandmother, Julia, in New York City. Julia had followed him soon after he first arrived there so she could take care of him, as she had in Pittsburgh. My older siblings have memories of him from his Pittsburgh days as a Carnegie Tech student before he left for New York in 1949. I eventually followed in his wake, hearing endless stories from my father, Paul (Andy’s oldest brother), my grandmother, Andy’s many relatives, childhood friends, college classmates, professors, his fifties crowd, and finally his Silver Factory crowd. My first memories of Andy were of a very busy illustrator—ever a workaholic—already with a different name than ours. Oh, about why the name change from Warhola to Warhol, a question I’m often asked. He dropped the 'a' simply because his name was easier to pronounce without it—not because he knocked the ‘a’ off trying to hit a roach coming out of his portfolio while on his first interview, as my father used to tell.

In Pittsburgh, he was Andrew Warhola, the youngest of three and the only one destined for a higher education. Enough can’t be said about his mother, Julia, and her strong influence. I remember her as a very special, spiritual immigrant woman straight from the ”old country,” who was creative on all fronts: music, dance, art, and storytelling. Andrej, Andy’s father, complemented the parental influence with his strong work ethic. Both of them nurtured the essence of Andy Warhol with their Carpatho-Rusyn heritage straight from the Carpathian Mountains in Slovakia. Their bond was tight, especially since Andy spoke their native dialect, Rusyn, as his first language.

Thanks to some money his parents had put away, Andy was able to go to the local college which was within walking distance, Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University). Carnegie Tech was mostly a science and engineering school, yet it had a strong art department that stressed solid design principles. Carnegie Tech’s approach to art emphasized creative freedom and expression, which was encouraged over academic realism. I had the good fortune to study with a few of his former professors, who loved telling Andy stories. Though he almost flunked out, the shy, awkward art student eventually became the class star. He left strong impressions on his fellow students and teachers. His class of 1949 included an exceptional group of students, many of whom became successful in other areas of art and design.

Andy Warhol’s career as an illustrator started during the summer of 1949, practically the minute he stepped off a bus in New York City with fellow art friend, Philip Pearlstein. Who knows what the art world would be like if Pearlstein hadn’t obtained permission from Julia to take Andy to New York? Andy’s only other option would have been staying in Pittsburgh and becoming a public school art teacher.

Andy’s illustration portfolio consisted of charming, expressionistic images that utilized his favorite college technique, the “blotted line” method. Art directors immediately fell in love with the spontaneous look. Soon that look became a favorite of art directors at book publishers, record companies, and advertisers.

Though Andy’s illustration career only spanned about twelve years, it was enough to make him a very successful and wealthy professional. His workaholism made him incredibly productive. He could never turn down a job offer, and soon needed an assistant to help him meet deadlines. He worked with many of the best art directors and designers in the business, which allowed him to perfect his intuitive skill as a designer and colorist. It was the best twelve-year master’s art program that anyone could have. More important, his drawing skills improved dramatically, from the nervous, jittery line of his college days to a line that was silk-smooth. When I was a youngster, watching him at his desk often late into the evening, I would see him pick up one shoe at a time and with his other hand draw it as if he were doing choreography with ink and pen—very hypnotic for a five-year-old to watch. Thus began my ambition to be an illustrator like Uncle Andy.

Besides the “blotted line” technique, he also discovered that he could make art by carving gum erasers. Although similar to linoleum printing, a carved gum print was much quicker and easier to make. He found a source for large four-inch slabs of gum erasers which produced a larger image. He could draw and cut one of these within an hour and then use it to print images repeatedly. These images, each slightly different, achieved the spontaneous look he was aiming for. His fascination with printing may have started as a three-year-old when my father showed him how to pull the ink off the Sunday funnies using soft wax. Andy’s interest in mass-produced imagery continued when he discovered silk screening.

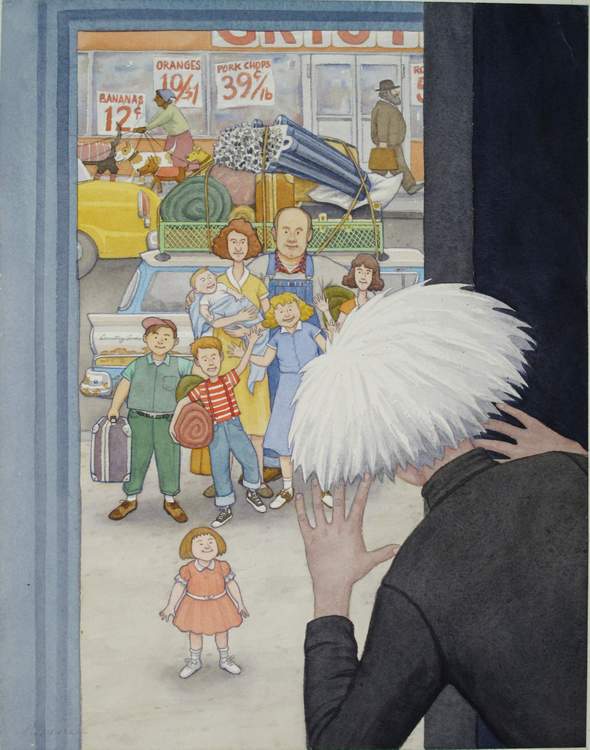

When I describe my uncle as “eccentric” in those days, I mean that he was different from men like my father and all the other burly steelworker types in Pittsburgh. In New York, my uncle was a thin, delicate, bespectacled guy drawing pictures at a desk. One would have never known he was one of the Warhola clan. Andy was very comfortable with us seven kids, more so than he was with adults. He was playful, easy-going, talkative, humorous, and at times a disciplinarian, since we weren’t always angels. Andy and Julia’s house had a very cozy family atmosphere when we would crash with them for visits. You may refer to my book, Uncle Andy’s, for further details about those visits.

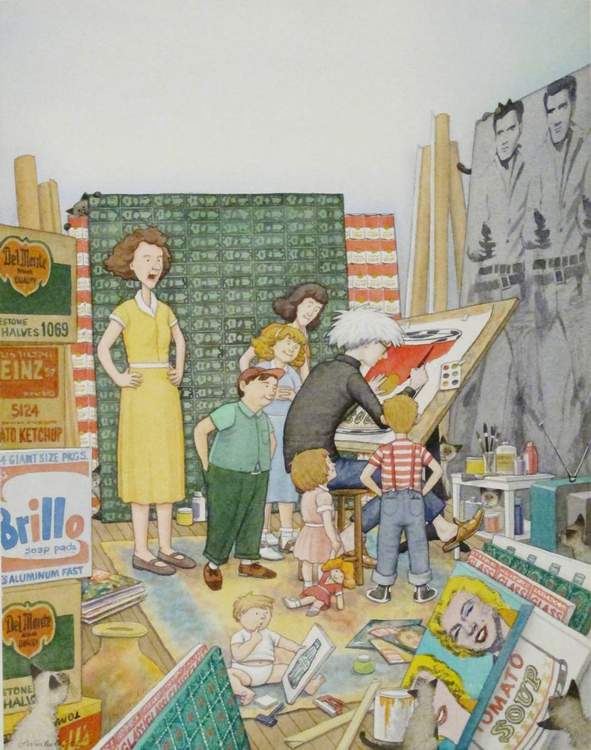

Our family didn’t grasp the deeper meaning of his art. We accepted the first drippy Pop images as larger versions of his commercial work. Eventually his paintings became less brushy and more colorful. It was only after the house started filling up with stacks of paintings and rolls of canvases that we knew that something different was happening. Even though we often visited unannounced, he remained very focused on his mission of painting canvas after canvas. I don’t think we ever interrupted his flow as he continued to produce many versions of everything: Coke bottles, soup cans, dollar bills, Marilyn images, “fragile” labels, comics, S&H green stamps, movie stars, newspaper headlines, telephones, nose job ads, dance step diagrams, paint-by-numbers, etc., etc.

All of this came out of two small rooms in about 1962. To the family, his art was very special but we had no idea of his bigger concept. He was simply mirroring society with all of these recognizable images. Ultimately, it was the soup can that became his strongest image—a very simple, stark, familiar, and most of all, ordinary object. It’s hard to believe that it was this image that got him noticed with such a splash. From that point on, he was our ”famous” Uncle Andy.

His last home studio assistant, Nathan Gluck, continued to stop by the house to help out with his later illustration jobs, but it was my older brother Georgie and I who first helped him to stretch canvases. Andy knew that we worked well in my dad’s junkyard. We took instructions and were good with our hands, so he would keep us very busy during our visits. Little did we know that many of these early Pop canvases would end up in museums throughout the world.

As for Andy’s interest in my becoming an artist, he was always very encouraging—showing me art-related methods and giving me his old art supplies: brushes, paints, and canvas. Upon my graduating from Carnegie Mellon and moving to New York to pursue a career as an illustrator, he tried to persuade me to go into photography and filmmaking instead. He said that illustration was a dying field, which may have been true due to the increased use of photography. I didn’t want to believe it. I stuck with illustration hoping to find my own niche.

Though my inspiration and encouragement to be an artist came from Uncle Andy, I am more connected to Norman Rockwell in substance and style. While I was growing up, Rockwell was ubiquitous to me. I could not help but be excited by his wonderful narrative images. As an art student I soon became aware that I was not the experimental, expressionistic type, but more interested in traditional realism. When I arrived in new York in 1977, I realized that I needed to improve my painting skills, so I attended the Art Student's League—Rockwell’s school. There I studied with academic painting teachers and learned traditional oil painting techniques. Whenever there was an original Rockwell painting hanging somewhere in the city, my fellow art students and I would make a beeline to that particular gallery. We loved Rockwell’s characterizations and his technique. My interest in the narrative led me to the publishing field, doing paperback covers, children’s books, and images for Mad magazine.

My uncle’s reputation grew in the art world and he is now a household name. Yet, he never forgot his roots in illustration. He showed a keen interest in my illustration work, always admiring the projects I was working on even though they were unrelated to his own. His appreciation for the visual had no boundaries, whatever its original intent.

Inventing America: Rockwell and Warhol brings together two extraordinary image-makers. No matter how different their art may appear, it’s nice to see them in a historical context together as a reflection of how our society has evolved. This exhibition also brings to the forefront the similarities and differences between illustration and fine art. Uncle Andy would have been thoroughly delighted to have his work hanging next to Norman Rockwell’s—so much so that I can just hear him saying, “It’s so greeeeat! Everything looks so absolutely marvelous.”