A Brief History and Analysis of Tattooing in

the United States from 1790 to 2020

by

Sarah Etherton

The first time I walked into a tattoo shop when I was in college, I was immediately greeted by the smell of disinfectant and the sounds of the machines buzzing. I was intimidated by the inked men and the crazy tattoo designs framed on the walls. Pin-up girls and kewpies smiled down at me while ferocious looking dragons and tigers grimaced. As I nervously handed my first tattoo concept (quickly sketched on printer paper) to the artist I noticed bold black and red ink forming a rose on the back of his hand. “That must have hurt,” I thought to myself, suddenly wondering what I was doing in this place. I was about to get ink injected into my skin; a permanent mark. Of course, I did not know then that this would be the first of many tattoos that I would collect, but I also did not realize that in the moment the first quick needles poked me, I was joining in a practice that has been part of human history for thousands of years.

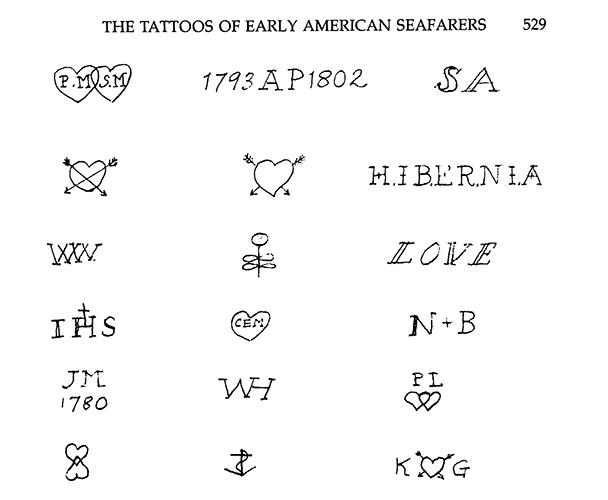

Fig. 1. Visual log of tattoos seen on sailors in a survey done in 1809. (Ira Dye, “The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 133, no. 4 [1989]: 520-554.)

Even now archeologists are discovering older and older preserved bodies that feature the distinctive black marks of charcoal ink punched into the skin with early tattooing tools. In North America, indigenous people of tribes such as the Navajo, Mohawk, and northerly Inuit, have used tattoos in their culture several hundred years before the first European colonists arrived on the continent.[1] (It is not within the scope of this paper to thoroughly discuss the rich history of tattooing among the indigenous peoples of North America, and while I primarily will discuss the appropriation of Samoan and Maori tattoo designs, modern Native American tattooing traditions are also appropriated in American tattoo culture.) I would be remiss to say that tattooing started in the United States with the American sailors of the 19th century (fig. 1). However, the tattooing practice in the United States that has grown so much in popularity today largely found its origins among the seamen who sailed in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[2]

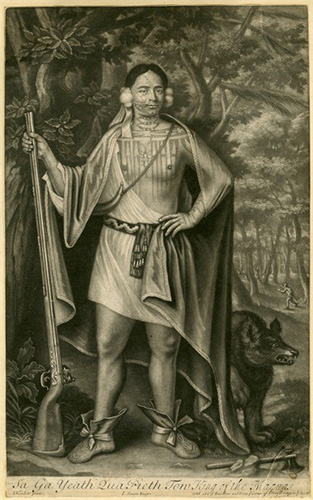

Fig. 2. Etching of Mohawk Chief Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow with tattoos on chest and face, ca.1710. Credit: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

While there is a recorded history of tattooing traditions in Neolithic Germanic, Anglo Saxon, and Gaelic communities, the people who sailed to the colonies to live in the early settlements of the New World had not practiced voluntary tattooing for hundreds of years.[3] It is important to distinguish ‘voluntary’ tattooing because the practice of tattooing criminals and slaves was practiced and would have been familiar to these colonists.[4]

When colonists first arrived in the Americas, they would have seen tattoos on the indigenous people they met (fig. 2). However, colonists did not adopt this practice from the indigenous tribes with whom they encountered and cohabited. One of the earliest official and visual records of European Americans with tattoos was documented in 1790. It is noted that sailors had been seen with tattoos before this, and men reported having the tattoos years before the record was written.[5] When American seafarers started sailing into the Pacific Islands, such as Samoa (whose word “tatau” was the origin of the word “tattoo”), sailors would have seen tattoos on the skin of the indigenous people there.[6] It is after this interaction with these tattooed individuals that historical records note the presence of tattoos on European American sailors.[7]

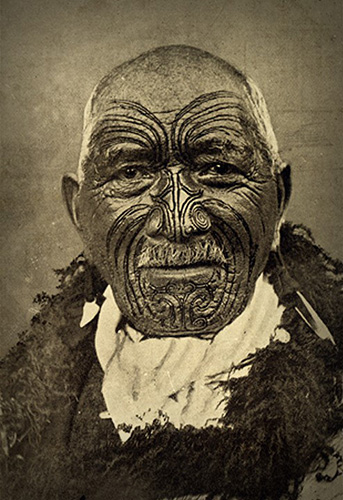

It is interesting to note the difference between the tattoos that the European American sailors received and the designs they would have seen on the Maori or Samoans they encountered (fig. 1 and fig. 3). There are also clear threads of designs that have continued into American traditional style tattoos today, such as hearts with Cupid’s arrow, anchors, initials, and religious imagery (fig. 1). This early record also describes the sailors’ reasons for the tattoos, including important dates for their loved ones back home, and also to denote having done something important (such as traveling a far distance).[8] These motives echo the purposes of tattoos in other cultures beyond the Polynesian influences, most directly inspiring the practice among sailors and people in modern times.[9][10]

Fig. 3. Maori community leader with ta moko on his face, ca.1905. Credit: PBS 2003.

While there are records of seafarers with tattoos as early as 1790, the practice of tattooing was largely relegated to those who sailed, either in the military or for trade.[11] Specifically, those in the enlisted military might have received tattoos as officers were prohibited, perpetuating the difference in status that tattooing denoted.[12] Tattooing was still seen as taboo, even as the first brick and mortar tattoo shop opened in New York City in 1846.[13]

While historically considered separate from illustration or other forms of art, contemporary thinking about what constitutes a piece as ‘illustration’ has changed. In History of Illustration by Susan Doyle, Jaleen Grove, and Whitney Sherman, illustration is defined as art that, “serves the purpose of documenting, narrating, persuading, or ornamenting.”[14] I believe that this definition firmly puts tattooing into an illustrative practice, as it not only ornaments the body but also is used to document important events. In this mindset, tattooing traditions as they emerged in the mid-19th century can be compared to the ‘Golden Age of Illustration’ that occurred at this time as well.[15]

During the mid-19th century, art in the United States was undergoing major changes. With the wide use of new printing presses and commercialization of products that would normally be homemade, illustrations were being printed and utilized more than ever before. Artists who worked primarily in these media were in high demand, and the profession of illustration became lucrative. Now art, something that had been exclusive to the wealthy, was accessible to anyone. Illustrations adorned magazines, canned soups, and posters hung in windows.[16]

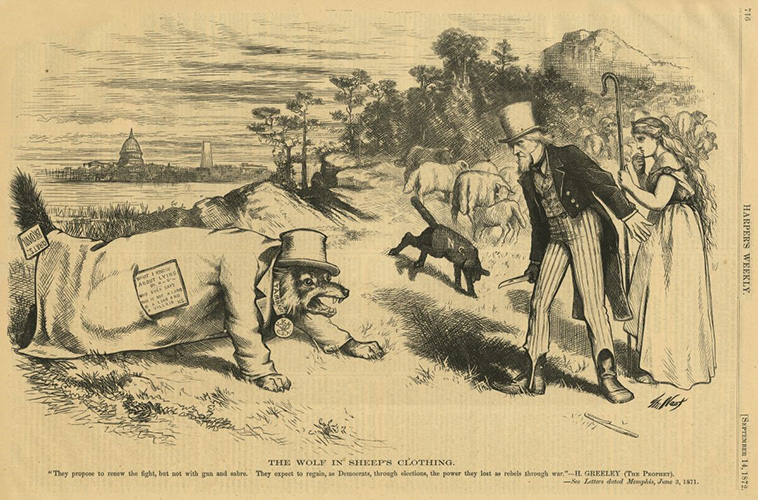

Similar to the way tattoo motifs were used to represent similar accomplishments among sailors, illustrators used motifs to evoke certain memories, feelings, or reactions to their work. For example, the German-American illustrator Thomas Nast used images of Columbia and Uncle Sam (fig. 4) to depict America, and a ‘wolf in sheep’s clothing’ to represent someone who may not be what they seem (in this case the Democratic Party) in his political cartoons.[17]

Fig. 4. Thomas Nast, “The Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing,” utilizing Uncle Sam, Columbia, and the ‘wolf in sheep’s clothing’ motif. Credit: New York Historical Society, 2018.

As demand for illustration grew in the United States from the 1850s through the 1920s, it is interesting to notice that the practice of tattooing was slowly growing in popularity as well.[18] While still very much a taboo among the American upper and middle classes, people other than sailors and those enlisted in the military were getting tattoos in growing numbers. Tattooed ladies started appearing in traveling shows. Working men were getting the names of their sweethearts tattooed onto their arms.[19] This popularity grew over the 20th century and, finally, in the 1980s and 1990s tattooing started to emerge into mainstream culture.[20]

With the surge in tattoos in popular media and on celebrities, Americans with tattoos showed off different styles in their collections. Rather than stick to the American traditional styles that sailors and others were getting at the beginning of the 20th century, tattoo artists brought tattooing traditions from around the world back home to the United States. Dragons and geishas styled after Japanese tattoos and imagery became popular as well as the bold lined ‘tribal’ style that mimicked the Polynesian tattoos that had influenced European American sailors 200 years earlier.[21]

As more and more Americans got tattooed, it was beneficial for tattoo artists to learn the different and popular styles that customers would want.[22] In the tradition of tattoo apprenticeship, an aspiring artist would train under an experienced tattooer and practice drawing in the style and tracing images that he or she wanted to tattoo. The common practice of ‘flash’ or collections of tattoo ideas that artists use to advertise their work, often featured common motifs in the style in which they trained.[23]

As styles influenced by Polynesian, Japanese, and other traditions became more popular, more artists trained to work in these ways to cater to customers’ requests.[24] The pervasion of this imagery caused a wide gap to grow between the culture from which these tattoo traditions originated and the Americans who were getting them. The more tattooing motifs were perpetuated, the fewer Americans knew about where those motifs came from.[25] Widespread cultural appropriation in the tattoo industry started to gain momentum.[26]

It is important to differentiate between the terms ‘appropriation’ and ‘cultural appropriation.’ Appropriation is a common and longstanding practice for artists. In art making, it is any time an artist co-ops imagery from another piece into their own. A printmaker might take commercial imagery and use it in his or her own piece. The American artist Andy Warhol is a classic example of an artist who used appropriation in his work, taking American commercial images like photos of Elvis Presley or the Campbell’s Soup can, and incorporating those images into new pieces.[27]

Cultural appropriation, however, refers to a dominant culture co-opting something integral to a culture experiencing oppression.[28] For example, in the 1940s and 1950s musicians like Elvis Presley took music that was almost exclusively performed by Black musicians for Black audiences and adapted it into his own style. He and artists like him were then credited with the emergence of “Rock and Roll” music in the American mainstream, even though they were using a type of music originated by others who were not allowed the same exposure by virtue of their race. In this way, white musicians culturally appropriated a style of music from the African American music scene.

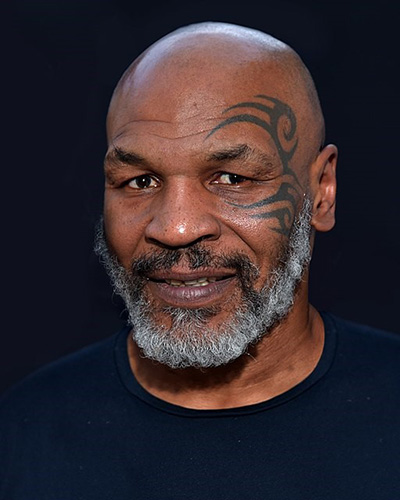

It is important to discuss and inform oneself about cultural appropriation because it can be damaging to the oppressed community. Traditions such as music or tattooing have generations of history in these communities, and that significance can be ignored, minimized, or even destroyed by cultural appropriation. Furthermore, often the features co-opted from these communities were once or still may be used to discriminate against the people who traditionally practice them. For instance, the Maori people of New Zealand were historically ostracized for their ta moko (the Maori term for a tattoo) on their faces, however, celebrities like Mike Tyson (fig. 5) have facial tattoos without a similarly negative connotation.[29]

Fig. 5. Mike Tyson with facial tattoo design coopted from traditional Maori ta moko designs. Credit: © Glenn Francis, www.PacificProDigital.com

These are some examples of cultural appropriation that can occur in many places around the world among many different communities. It does not only occur in the United States, but for the purposes of this analysis, cultural appropriation will specifically refer to American people co-opting tattooing traditions from oppressed communities, primarily those indigenous to the Pacific Islands, such as Samoa and New Zealand.

One question that arose as I researched the history of tattooing in the United States was why cultural appropriation seems so pervasive in the American tattooing community. The origin of the practice itself in the United States was primarily adopted from the Polynesian people by European American seafarers, but the designs were not.[30] It was not until the 1980s that the emergence of ‘tribal’ tattoo styles took hold in the American tattoo industry. Suddenly, designs that were distinctly from different parts of the Pacific Islands, such as ta moko in New Zealand and tatau in Samoa, appeared on American arms, chests, and backs. It was not clear why these particular designs rose in popularity, but when celebrities (both of Maori and Samoan descent and non-Maori/Samoan descent) started showing these tattoos, the trend was set.[31]

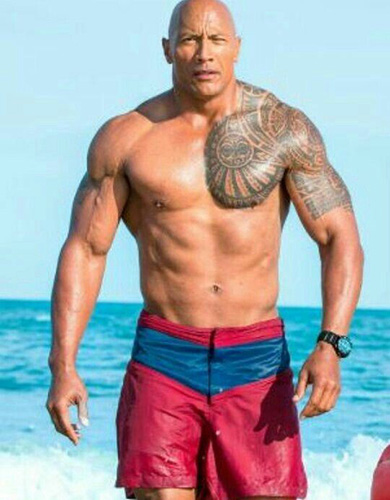

Fans of celebrities like Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson might admire him for his strength, humor, or good looks. Although, not everyone is aware that he has Samoan heritage, and the tattoo he sports on his chest and left arm is representative of that heritage and specific to Samoan people and culture (fig. 6). Someone might see tattoos on celebrities they admire and want these tattoos themselves. While Johnson is an example of a person honoring their own heritage with his tattoo, there are plenty of celebrity examples of non-Maori and non-Samoan Americans getting tattooed with these designs simply for the aesthetic. Mike Tyson is not of Maori descent and sports a ta moko design on his face (fig. 5). The popularization of the Polynesian-inspired tattoo has even grown beyond celebrities, being featured in ‘temporary tattoo’ packs and on ‘fake tattoo sleeve’ garments.[32] While some might argue participating in trends like this is harmless and fun, there is a very important history that is being ignored in the commercialization of ta moko and tatau.[33]

Fig. 6. Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, with his Samoan tattoo, honoring his Samoan heritage. Credit: assets.com

The Maori people of New Zealand traditionally believe that the face has incredible spiritual importance, and when an adolescent receives their ta moko it is an important milestone in that young person’s life. The ta moko on a person’s face communicates who their family is and their role in a community. The Maori also believe that someone’s spiritual essence is displayed through their ta moko. Traditionally the designs were ‘carved’ rather than stamped into the skin, and a full face ta moko can take over a year to finish, although needles and tattoo machines are now used.[34]

In Samoa, the tattooing tradition has been practiced for over 2,000 years. The practice is passed from parent to child and many practitioners in Samoa still use traditional tools to imprint the ink.[59] Tattoos each have their own significant meaning and could denote someone’s rank, familial heritage, strength, and endurance.[35] (As noted earlier in the paper, to properly discuss the history and significance of ta moko and tatau in Maori and Samoan culture respectively would require many years of research, extensive writing, and interaction and experience with the people from the cultures studied.)

In both Samoan and Maori culture, receiving a tattoo is an important and sacred process, built upon centuries of tradition and heritage. Selling ta moko temporary armbands for parties or getting tatau designs tattooed because of the way they look ignores the significance that this tradition holds to Samoan and Maori people.

Another question that is important in this discussion is how Maori, Samoan, and other Polynesian people themselves feel, and what they have to say about the widespread use of ta moko and tatau designs in American culture. PBS published a series of articles called “Skin Stories” interviewing various members of Polynesian communities on their experience with their tattoos and appropriation of tattoos on others.[36] While the testimony of a few individuals does not speak for the entire community, it is helpful to hear what some have to say.

Manu Neho, a Maori woman who grew up in the Bay of Islands and Auckland, initially rejected her heritage after the death of her grandfather and her family’s belief in the Mormon Church, but as she got older she reconnected with her roots and decided to get a ta moko on her chin. The ceremony to receive her ta moko was a weekend-long event attended by her close family and friends. It was an emotional and sacred occasion for Neho. In getting her ta moko on her chin, which depicts a shark swimming to represent her mother coming to New Zealand and meeting her father, Neho reclaimed her Maori heritage. She recounts seeing others with moko designs and, “would see [non-Natives with moko] as an affront to that particular culture…and I do feel affronted when people just blatantly disregard process.”[37]

Professor Te Kahautu Maxwell at the University of Waikato, who is a Maori man with ta moko on his face, commented in an article discussing ta moko on white women that these tattoos are, “the Maori deciding to reclaim their heritage and identity” and that “we have to protect the last bastions that we have as Maori that makes us different.”[38]

This is not meant to condemn tattooing in the United States, or to be the definitive source for whether a tattoo is right or wrong based on one’s heritage. The importance of this research not only into cultural appropriation in tattooing today, but also the history of tattooing in the U.S., is to learn about where the practice comes from, where particular designs come from, and to further the conversation about preserving cultural heritage in oppressed communities. As an American tattooed person, I believe it is important to acknowledge one’s part in a very long history, of the tattooing practice as well as colonization and cultural appropriation. Although tattooing is and will continue to be a popular form of expression in the United States, the history and cultural significance of certain imagery is still strongly threaded to oppressed communities around the world, which is important to acknowledge.

[1] Ira Dye, “The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 133, no. 4 (1989): 520-554.

[2] Mary Kosut, “An Ironic Fad: The Commodification and Consumption of Tattoos,” The Journal of Popular Culture 39, no. 6 (2006): 1035-1048.

[3] “Tradition Unbound: Tattoos beyond Polynesia,” PBS Skin Stories: The Art and Culture of Polynesian Tattoo 2003. https://www.pbs.org/skinstories/history/

[4] Dye, “The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818,” 520-554.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Josep Perez Marti, “Tattoo, Cultural Heritage, and Globalization,” The Scientific Journal of Humanistic Studies 2, no. 3 (2010): 1-9.

[7] Dye, “The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818,” 520-554.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “Tradition Unbound: Tattoos beyond Polynesia,” https://www.pbs.org/skinstories/history/

[11] Josep Perez Marti, “Tattoo, Cultural Heritage, and Globalization,” The Scientific Journal of Humanistic Studies 2, no. 3 (2010): 1-9.

[12] Dye, “The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818,” 520-554.

[13] “Tradition Unbound: Tattoos beyond Polynesia,” https://www.pbs.org/skinstories/history/

[14] Susan Doyle, Jaleen Grove, and Whitney Sherman, History of Illustration (New York : Fairchild Books, 2018).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “American Woman? Amerique, Columbia, and Lady Liberty,” New York Historical Society: Women at the Center, October 23, 2018. http://womenatthecenter.nyhistory.org/american-woman-amerique-columbia-and-lady-liberty/

[18] Mary Kosut, “An Ironic Fad: The Commodification and Consumption of Tattoos,” The Journal of Popular Culture 39, no. 6 (2006): 1035-1048.

[19] Christina Parrella, “Tattoo You: A History of Tattooing in New York,” NYC the Official Guide, Feb. 17, 2017. https://www.nycgo.com/articles/tattooed-new-york-nyc-tattooing-history

[20] Kosut, “An Ironic Fad: The Commodification and Consumption of Tattoos,” 1035-1048.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Parrella, “Tattoo You: A History of Tattooing in New York,” https://www.nycgo.com/articles/tattooed-new-york-nyc-tattooing-history

[24] Kosut, “An Ironic Fad: The Commodification and Consumption of Tattoos,” 1035-1048.

[25] Mika Young, “Ta Moko and the Cultural Politics of Appropriation,” Sites: New Series 15, no. 2 (2018): 1-15.

[26] Kosut, “An Ironic Fad: The Commodification and Consumption of Tattoos,” 1035-1048.

[27] Liz Linden, “Reframing Pictures: Reading the Art of Appropriation,” Art Journal Vol. 75, Issue 4 (2016): 40-57.

[28] Young, “Ta Moko and the Cultural Politics of Appropriation,” 1-15.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Dye, “The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818,” 520-554.

[31] Kosut, “An Ironic Fad: The Commodification and Consumption of Tattoos,” 1035-1048.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Young, “Ta Moko and the Cultural Politics of Appropriation,” 1-15.

[34] “Tradition Unbound: Tattoos beyond Polynesia,” https://www.pbs.org/skinstories/history/

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] “Maori face tattoo: It is OK for a white woman to have one?,” BBC News, May 23, 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-44220574

__60_60_c1.jpg)