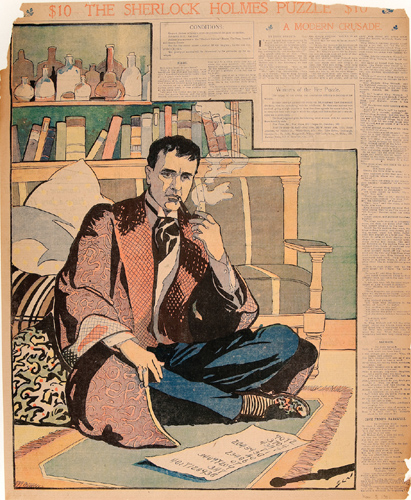

Fig. 1. John Sloan, The Sherlock Holmes Puzzle, from the Philadelphia Press, March 3, 1901, Delaware Art Museum, John Sloan Manuscript Collection

Over the summer, many visitors to the Delaware Art Museum tried to solve the The Sherlock Holmes Puzzle, a brainteaser designed by John Sloan (1871-1951) for the Sunday supplement of the Philadelphia Press of March 3, 1901. Sloan’s puzzle asked readers to “solve the problem of the paper on the floor,” which requires holding the newspaper up to a mirror to decipher a message. The surrounding image depicts a handsome Holmes seated on the floor of a Victorian study filled with books, beakers, and questionable decorating decisions. The detective’s attire, including in a smoking jacket, patterned slippers, striped socks, and rings on two fingers, conveys a rather louche and bohemian Holmes—more Robert Downey Jr. than Basil Rathbone—who is immediately familiar over one-hundred years later. And Sloan’s Holmes is convincingly individualized, yet, unlike many of the men in Sloan’s early illustrations, he does not resemble the artist or his friends. This set me to wondering about the visual history of Holmes. Although the editions of Arthur Conan Doyle’s books that I own are not illustrated, what sources for Holmes imagery were available to Sloan?

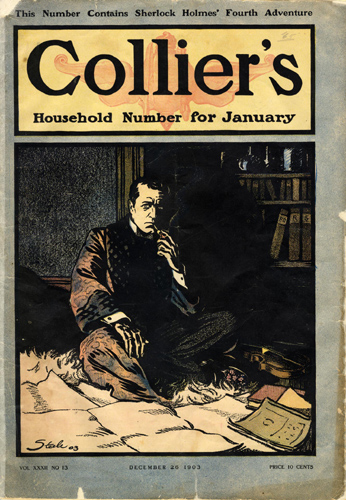

Fig. 2. Frederic Dorr Steele, Cover illustration for Collier's Magazine, December 26, 1903

A quick internet search yielded a nearly identical image by Frederic Dorr Steele (1873–1944) for Collier’s Magazine. Steele is the American illustrator most closely associated with Sherlock Holmes, having illustrated several stories for Collier’s when they were first published in 1903 and 1904. His images are striking, displaying a poster-style aesthetic with elegant outlines and broad swaths of flat color and pattern very similar to Sloan’s work for the Philadelphia newspapers. A logical source for Sloan, except that the timing didn’t work: Steele’s cover is dated 1903 (and was published on the cover of Collier’s in December 1903), and Sloan’s newspaper puzzle was published in 1901. And while it is possible that Steele borrowed from Sloan, this seems less than likely, as Sloan’s puzzle had appeared in a Philadelphia newspaper years earlier.

Having begun to delve into Holmes illustration, I assumed both Sloan’s and Steele’s images might have their source in a drawing by Sidney Paget, who illustrated the Holmes stories for The Strand magazine, but a review of these on the Victorian Web yielded a very different Holmes. Paget’s Holmes is slender and fine-boned with a notably receding hairline. He fits a type—intellectual, a bit effete—that would have been immediately recognizable to Victorian readers in England and the United States, and he is a far cry from the handsome, square-jawed detective of Sloan’s and Steele’s depictions. Paget’s Holmes wears a smoking jacket on occasion and inhabits a Victorian interior, but (with one exception in 1891) he doesn’t sprawl on the floor, and the rings and aggressive patterns are nowhere in evidence.

Further research on Steele pointed in a different direction. According to an inscription on an original drawing at The Players in New York, Steele’s version of Holmes was modeled on the actor William Gillette, who starred in the play Sherlock Holmes which opened in 1899. Gillette also authored and stage-managed the production (with approval from Arthur Conan Doyle), performing as Holmes some 1,300 times in his long career. As witnessed by Sloan’s and Steele’s illustrations, Gillette’s performance—with the deerstalker cap, calabash pipe, and voluminous smoking jacket—immediately influenced popular visions of Doyle’s hero. During its first run at the Garrick Theatre in New York, a critic for The New York Times predicted in their November 7, 1899 edition that “Sherlock Holmes’s triumph on the stage will equal if not fairly surpass his triumph in the circulating libraries.” When Sherlock Holmes opened in Philadelphia on January 28, 1901, it was, to quote the Philadelphia Inquirer of February 3, “literally the sensation of the hour.” This high-profile theatrical engagement must have been what sparked Sloan’s puzzle. A fan of the theater, Sloan created a clever and timely puzzle within weeks of the opening, playing on the interest of his audience. Sloan’s image is drawn from Act II, when Holmes ruminates on a problem in his rooms at 221B Baker Street, but the play itself may not have been the direct inspiration for Sloan’s composition.

A photograph of Gillette as Holmes, taken at the New York studio of Napoleon Sarony, captured him cross-legged on the floor in the very same pose used by Sloan, and Sloan’s Holmes resembles Gillette down to the position of his hand and the rings on his fingers. Produced for publicity, the photograph appeared in The Strand in December 1901, and it may have been disseminated earlier (though it did not appear in the Press or the Inquirer in 1901). Sloan certainly would have seen a publicity photograph as fair game. In the 1890s, before the widespread use of the half-tone process in newspapers, one of Sloan’s responsibilities as a newspaper illustrator was to copy photographs of famous people for reproduction in the newspaper.

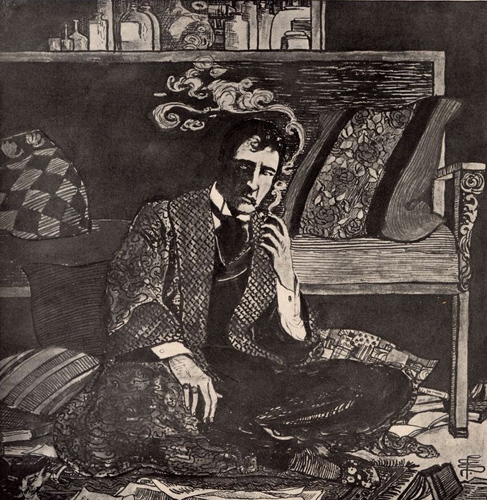

The Sarony photograph was almost certainly the source for an illustration by Gillette’s cousin, the young illustrator Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951), who produced a souvenir booklet entitled, William Gillette as Sherlock Holmes, published by R.H. Russell in 1900. Smith’s illustration features the now-familiar pose, complete with a couch and cluttered shelf. The profusion of patterns is present, as is the drifting pipe smoke. Smith’s is the nearest in spirit and composition to Sloan’s puzzle. However, I have been unable to determine if Sloan saw her work—it certainly wasn’t a common book and she was not a famous illustrator—though the visual evidence strongly suggests he did.

Investigating this illustration reminded me of the importance of theatrical, as well as printed source material for turn-of-the-century illustrators. Many illustrators enjoyed the theater and employed theatrical devices to convey narrative. And stealing a composition was not unusual, especially for illustrators on a deadline. Illustrators as accomplished as Howard Pyle borrowed compositional elements often, drawing on a wide variety of paintings, prints, and other illustrations. Sometimes they even rehashed their own illustrations, and Sloan was no exception.

Sloan conceived of and produced full-page, color puzzles almost every week for three years, and he searched everywhere for inspiration. He consulted books on puzzles and looked at other picture-puzzles that appeared in the popular press. Even the “non-puzzling” elements of his illustrations, like the figure of Holmes, show the influences of art nouveau posters, Japanese woodblock prints, and British children’s books. Sloan was one of the most exciting newspaper illustrators at the turn of the century, and his newspaper work deserves scholarly attention. This summer’s exhibition, The Puzzling World of John Sloan—organized by Margarita Karasoulas, the Alfred Appel Jr. Curatorial Fellow at the Delaware Art Museum—was an important step forward in understanding this exciting body of work.

Fig. 3. Pamela Colman Smith, William Gillette as Sherlock Holmes, 1900

RESOURCES

1) The Victorian Web has links to reproductions of every Paget illustration of Sherlock Holmes.

2) The Holmes blog Always 1895 explains the source for Frederic Dorr Steele’s Holmes in the performances of William Gillette.

3) A website dedicated to Pamela Colman Smith provides helpful details and images of her Sherlock Holmes project.