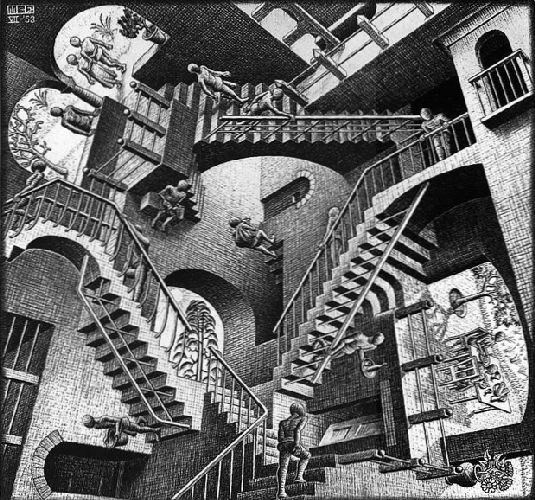

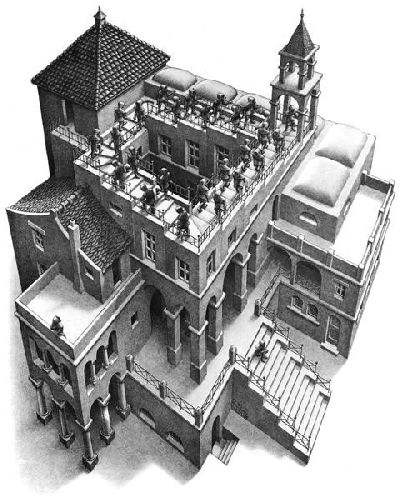

The Dutch graphic artist and printmaker Maurits Cornelis Escher (1898-1972) is world-famous for his prints of tessellations and impossible objects. His work has been reprinted, recolored, redesigned, and used as tattoos and album covers (often with little regard to the copyright). Numerous popular films, games, and comics have borrowed inspiration from his artwork as well. (For example, the staircases in both Jim Henson’s musical fantasy film, Labyrinth, and Shawn Levy’s comedy adventure film, Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb, were inspired by Escher’s Relativity [fig. 3]. The visual art style of the indie puzzle game, Monument Valley, by Ustwo Games is heavily influenced by Escher’s impossible architecture prints. In Kentarou Miura’s influential manga, Berserk, the scene of “Abyss” shares great similarity to Escher’s stairs prints.)

However, despite being very influential to popular culture, Escher’s work stayed somewhat neglected in the art world for a long period of time. Even now, although he was a highly skilled and productive printmaker, Escher’s work frequently gets frowned upon as being too much like illustration.

Escher’s own interpretation of his role and his work may be one of the main reasons that the artist is not treated seriously by the art world. He never regarded himself as an artist, simply referring to himself as a designer. In public, he always insisted that his prints carried no hidden meanings and were merely illustrations of interesting mathematician concepts.[1] However, no matter what caused Escher’s constant denial of hidden meanings in his work, his artworks stand on their own and speak for themselves. Whether conscious or unconscious, Escher’s experiences, emotions, and worldview are reflected in the artworks he made throughout his life.

The Life of M.C. Escher

Escher was born in 1898 in the Netherlands. Beginning in childhood, he suffered from various diseases and underperformed at school, partially due to the illness. The introverted artist was also constantly troubled by social anxiety. Despite these difficulties, he made many friends, built a family, and found his career path as an artist.

While in school, Escher studied architecture until one of his teachers, Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita (1868-1944), a Dutch graphic artist, discovered Escher's talent in art, and encouraged him to switch to graphic art.[2] During the training under de Mesquita, Escher quickly discovered his love for printmaking.

Escher also moved multiple times in his life. He lived in Rome from 1923 to 1935, when he and his family were forced to relocate due to the illness of Escher’s two children and the rising Fascism in Italy.[3] Afterward, the family spent several years in Switzerland and Belgium, and moved back to the Netherlands in 1941. Before eventually settling down in the Netherlands, Escher also took time for extensive travel in the search of artistic inspiration.

It is also worth noting that the artist lived through two World Wars, and one deadly pandemic in 1918. Compared with many people of the same generation, Escher may be considered a lucky and privileged person. Escher was not a direct target of the Nazis, and his parents’ wealth helped to keep him relatively safe during that turbulent time. However, Escher was not free from the stress and trauma associated with these events, especially during World War II. The artist had many Jewish friends who were killed by the Nazis, including his teacher, de Mesquita. The war left Escher deeply pessimistic about humanity, and the artist sought comfort in depicting imaginary scenes, rather than work based in reality.

During the last three decades of his life in the Netherlands, the artist dedicated himself to his work, and his fame grew continuously. At the same time, he gradually became isolated from his family and suffered from deteriorating health.[4] Escher passed away in 1972 at the age of seventy-three. During his life, he created 448 lithographs, woodcuts, and wood engravings, and more than 2,000 drawings and sketches.[5]

Social Anxiety, Portraits, and Stiffness of Figures

Throughout his life, Escher struggled with some level of social anxiety, which is reflected in the artist’s work. Declaring himself to be “shy about noise and movement,” Escher refrained from socializing with people face to face. He seldom drew portraits—having someone sit for him as a model was too much for him to handle.[6] Most of Escher’s portraits are of himself, observed through a mirror. The artist created a few portraits of the people to whom he felt close, such as his father, wife, and sons. These rather personal artworks were rarely for sale. For example, the fifteen prints of the lithograph Escher made of his father in 1935 were created exclusively for sharing among family members.[7]

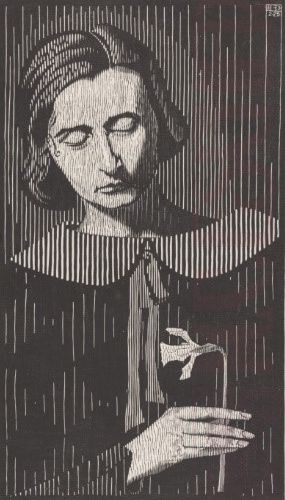

Both Escher’s self-portraits and portraits of other people show great technical skills and sharp observation. The prints that the artist made of his family members reflect his emotional attachment to them in subtle and delicate ways. One example of these portraits is a woodcut of his wife, Jetta Umiker, made in 1925 (fig. 1). This portrait was printed about half a year after the couple’s wedding in 1924, showing Jetta calmly holding a flower, with eyes closed, and seemingly deep in thought.

Fig. 1. M.C. Escher, Portrait of G. Escher–Umiker (Jetta), woodcut, February 1925

There is subtle round-shaped soft light behind Jetta’s head, resembling the glowing halo from the old religious paintings. The halo speaks of Escher’s admiration for his wife. The delicate shape of the thin, straight fingers and the flower stem echo each other, reflecting the artist’s perspective of Jetta at the time: beautiful, lovable, and fragile. Shapes are defined by values and textures instead of contour lines. Escher carefully used vertical lines of different lengths and weights to portray different elements in the print. The artist especially paid a lot of consideration towards the texture of Jetta’s skin. This texture composed of slightly curved irregular lines is achieved by carefully carving away the wood wavily, possibly using V-shaped chisels and round gouges. This technique is difficult due to the straight wood grain. The wavy texture on Jetta’s face and her right hand, contrasting with the straight and even lines elsewhere in the composition, effectively emphasizes the tenderness of the skin. The sophisticated skin texture also draws the audience’s attention to Jetta’s facial expression and hand gesture, which were clearly part of what Escher found extremely attractive and fascinating in his wife.

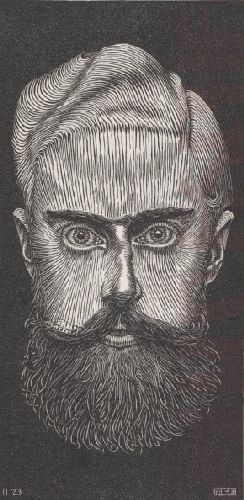

Fig. 2. M.C. Escher, Self-Portrait, woodcut, November 1923.

Escher’s Self-Portrait (fig. 2), printed in November 1923, was created by using a similar carving technique. The work was finished months after the artist’s engagement with his future wife. The skin texture in this print seems more rigid when compared to his wife’s portrait, done two years later. Instead of the wavy skin texture in Jetta’s portrait, Escher’s skin is made with radiating lines, effectively leading the audience’s sight to the artist’s gazing eyes. The strokes are straight and strong, showing the determination of a young artist who just started his career. This is Escher’s first self-portrait showing the artist’s iconic beard. He appeared to look confident, even if he might have been a little unsure of the future.

Contrary to these early portraits of himself and his family members, made before World War II, the figures in Escher’s post-war work are not very impressive. From the 1950s to the early 1960s, Escher created a series of prints featuring imaginary characters in impossible architecture constructions. Such body of work includes Relativity (1953) (fig. 3), Convex and Concave (1955), Belvedere (1958), Ascending and Descending (1960), and Waterfall (1961). Despite having perfect proportions, the poses and motions of figures in these prints are often quite unnatural. The stiffness may have originated from the lack of real-life models, due to the artist’s social anxiety.

Fig. 3. M.C. Escher, Relativity, lithograph, July 1953

The other interesting feature of the figures in these later artworks that possibly reflects Escher’s discomfort with socializing is the minimal interaction among the characters represented. Although multiple figures are featured in the pictures, these characters usually face different directions and focus on whatever they had at hand, indulging in their own personal world. The facial expressions of the characters are often blank or indifferent, as if they are not aware or not interested in the presence of others. In both Relativity (fig. 3) and Ascending and Descending (fig. 8), the characters’ faces are not even visible. The impossible architectural background emphasizes such psychological division among figures who exist in different realities with different perspectives and rules of gravity. These post-war prints by Escher, while created to illustrate impossible constructions, seem to convey Escher’s perception of the difficulties people have to reach out and understand each other at the same time.

A Self-Induced Loneliness

Printmaking is seldom a fast or easy artistic process; woodcuts and wood engravings are especially time-consuming and labor-intensive. As a printmaker with a complex, precise, and detail-oriented artistic style, Escher was extremely productive. However, this productivity took a toll on Escher's relationship with his family, and a growing sense of loneliness began to appear in his later prints, when the artist became more and more isolated.

While Escher was living in Rome from the 1920s to the 1930s, the artist’s work habits were already creating tensions in his family. When he tried to conceptualize a new piece of work, Escher had no tolerance for any interruptions and would get angry if any of his family members ever made too much noise. Not wanting people to see what he was doing, the artist locked himself in the studio and forbid anyone to walk by his window. The tension could last for weeks.[8] These habits barely changed throughout the artist’s life, as Escher believed that this kind of self-isolation was the only way he could possibly work.[9] After leaving Italy in the mid-1930s, Escher gradually discovered his own artistic voice. As he stated, “I started working with passion when I discovered that I myself had things that had to get out, that I can express something that someone else does not have.”[10] Escher’s increasing devotion of his time, energy, and attention to his work left his family feeling more and more neglected and abandoned. Eventually, the love and affection between the artist and his wife turned into frustration, anger, and bitterness.

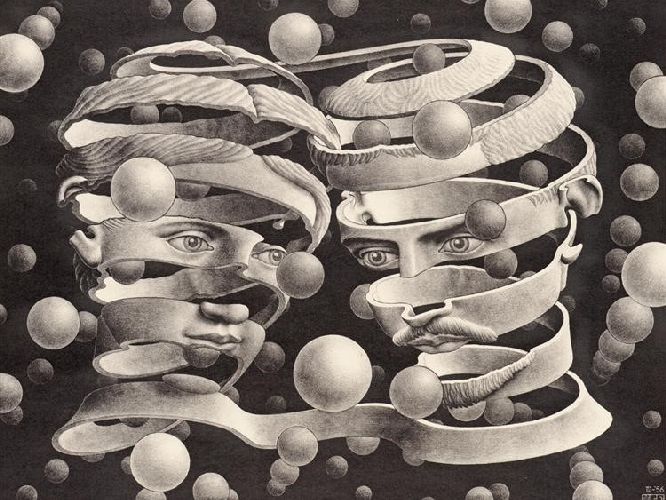

Fig. 4. M.C. Escher, Bond of Union, lithograph, April 1956

The built-up tension within the couple confused and frustrated Escher. In 1956, he created the lithograph, Bond of Union (fig. 4), possibly as a way to express the complex feelings of his relationship.

In the print, the heads of Escher and Jetta are represented and broken up into one connected strap. The two heads are hovering in the void, surrounded by floating bubble-like globes. The facial expression is pensive, almost sad. It looks as if although the two figures are connected and inseparable, as their personalities are disintegrating and getting dissolved into the void. In a 1968 interview, Escher claimed this piece to be merely an experiment to show the concept of endlessness and a reaction to sculpture.[11] However, he also wrote about this print, “Like an endless bond, even their foreheads are woven together, they form an inseparable entity. Whether these two are glad to be bound as a family together, I cannot tell. It is a perilous undertaking, and they look a little sad.”[12]

This is one of the rare portraits Escher made after World War II. However, this piece is significantly different from his portraits of himself (fig. 2) and of Jetta (fig. 1) made more than thirty years earlier. The same faces now appear reserved and indifferent. The figures are facing towards each other but there is no shared eye contact, almost as if the couple is avoiding each other. Escher’s facial expression, contrary to his confident look shown in the early self-portrait, seems troubled and tired.

Fig. 5. M.C. Escher, Waterfall, lithograph, October 1961

Escher’s print, Waterfall (1961), also seems to unconsciously reflect Escher’s struggle with the increasing distance in the relationship with his wife. In the final sketch of the print, two men and one woman were presented. However, in the finished lithograph, only a man and a woman remained.[13] The woman is focusing on the work at hand and the chores of real life, while the man is gazing idly at the impossible waterfall structure. There is a theme of parallel, duality, and contrast in this image. The viewer can see two towers connected by bridges. The river is flowing upwards while the waterfall is dropping down. While the towers are connected, and the water circulates in the river and the fall, they are connected only in an impossible way that cannot happen in real life. The composition seems to imply that, similarly to the towers and the river, the two figures are also only connected by a weak and unrealistic bond. This work may be a metaphor of the artist’s relationship with his wife: being together while staying separated, connected yet detached.

Nostalgia for Italy

Italy was an important place in Escher’s artistic life. He first traveled there in 1921 and fell in love with the Italian landscape and architecture. Escher revisited the country multiple times and eventually decided to settle down in Rome with his new family in 1925.

During the ten years spent in Rome, Escher was happy, motivated, and productive. The artist made mountain trips through desolate regions almost every year, usually in Spring. During these trips, he produced sketches, took photos, and kept a travel diary to record everything that inspired him.[14] The artist was especially interested in the southern Italian landscape, the Moorish architecture, and the rocks.[15] In fact, most of Escher’s landscape prints were created during his Italian period. These works were made with incredible skill and patience, conveying his love and passion for the subject. Escher was also impressed by Rome’s architecture as seen at night, intrigued by the light, shadows, and shapes created by the darkness and streetlights. This interest led to the creation of a series of woodblock prints featuring Rome’s nighttime cityscapes titled, Nocturnal Rome (1934), which showed impressive skill in manipulating values and textures.

Escher’s work in his Italian period was generally carefree and calm—even cheerful. He was financially well supported by his parents, had just built a family of his own, and started his own career out of college. He was surrounded by rich inspirations and the warm weather of Italy, and was absorbing information and improving as an artist every day. When the family had to leave Italy in 1935, losing that connection with his artistic inspirations left Escher very depressed. He then turned to the creation of “inner images.”[16]

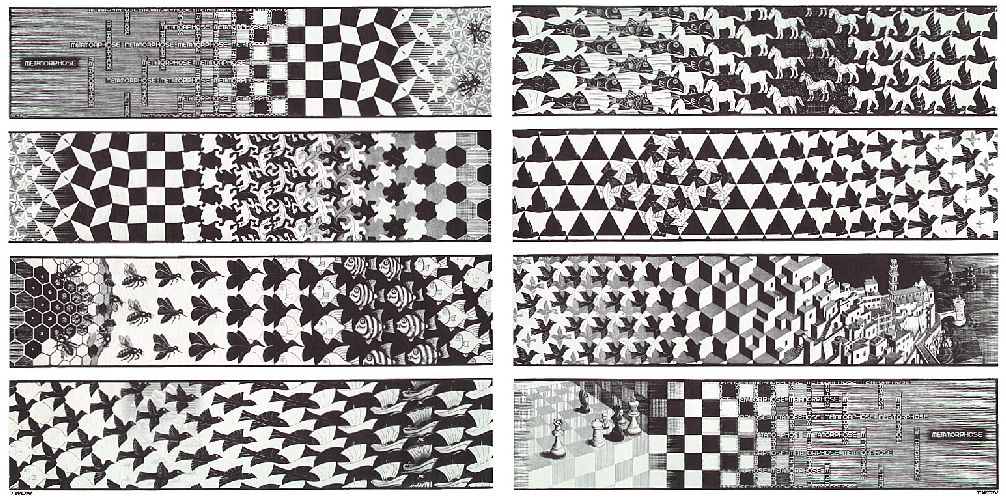

However, in the following decades, Escher frequently revisited the various inspirations he had gathered during trips when he was in Italy, to create nostalgic and melancholic compositions. For example, he portrayed the Italian town Atrani in all three of his famous Metamorphosis series (fig. 6). He also featured Moorish architectural elements such as arches and domes in all of his “impossible architecture” prints in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Fig. 6. M.C. Escher, Metamorphosis III, woodcut, 1967-1968

Trauma from the War

As with many other artists of the time, Escher was not free from the emotional toll caused by World War II. When the artist moved back to the Netherlands in 1941, the country was already occupied by Nazi Germany. The same year, the Nazis founded the “Kultuurkamer” (“Chamber of Culture”) in the Netherlands, an anti-Jewish propaganda agency created to serve the occupying force and its Fascist ideology. Becoming a member of “Kultuurkamer” meant a formal assent to the occupier; the artists who did not join would not be allowed to exhibit, publish, or make music. Deeply trouble, Escher wrote to his friend Hein ’s-Gravesande on December 1, 1941, “Since the complete exclusion of the Jews, I have had an unpleasant feeling whenever I exhibit, a sense of profiteering.” Escher despised the Nazis, but was also scared that if he refused to join the organization he would be left in danger, “alone or almost alone.”[17] However, Escher chose not to register, resigned from associations that had collective membership with the propaganda machine, and stopped exhibiting his work. On January 11, 1942, he wrote to ‘s-Gravesande again, “I find it easier to look my Jewish fellow artists in the eye now.”

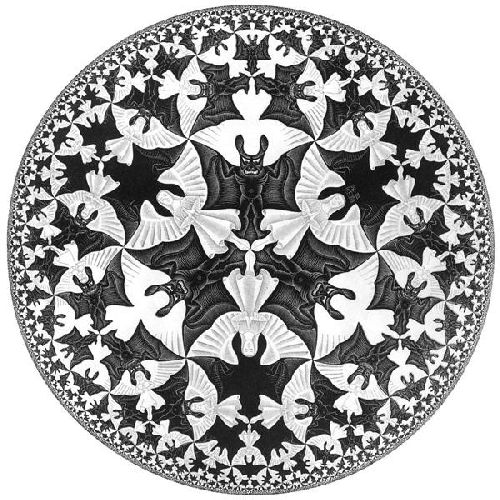

Fig. 7. M.C. Escher, Circle Limit IV (Heaven and Hell), woodcut, July 1960

During the time between writing the two letters of 1941 and 1942, likely torn by fear and conscience, Escher made a tessellation drawing of angels and devils titled, Regular division drawing nr. 45. In this drawing, white angels and black bat-like devils intersect. The devils are laughing menacingly, while the praying angels stay reserved and almost emotionless. This piece of work seems to be important in the artist’s mind since he revisited the design twice afterward: one time carved into a wooden ball (1942), and the other time made into Circle Limit IV (Heaven and Hell) (1960) (fig. 7), the last piece of his Circle Limits series. This tessellation design is one of the few artworks by Escher that presents the contrast of good and evil, and the confusion and disquietude when the two are interlocked together.

As the war progressed, many of Escher’s Jewish friends were killed by the Nazis. On January 31, 1944, Escher went for a regular visit to the home of his former teacher and long-time friend, Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita, hoping to bring his isolated family some apples. He arrived at an empty house with broken windows, and stepped over artwork scattered on his teacher’s studio floor. The entire Portuguese-Jewish family was taken away to a concentration camp, at which none survived.[18] The trauma of witnessing the tragedy of his teacher’s family lingered with the artist. Even in 1968, seventy-year-old Escher still claimed to, “have the greatest difficulty with the Krauts (German soldiers)” and could not bear hearing others speaking German.[19] The artist was never able to completely get over the loss and deaths brought by the war, and turned pessimistic about human society in his later years. He wrote to a friend, “It’s a pity that the world we live in is such a hopeless case. It’s an unfathomable while dangerous world, an irrational gamble. I myself prefer to live amongst obstructions that have nothing to do with reality.”[20]

Fig. 8. M.C. Escher, Ascending and Descending, lithograph, March 1960

This pessimistic view of the world is reflected in Escher’s lithograph Ascending and Descending (1960) (fig. 8). In the print, the roof of a building with an atrium in the center was turned into continuous stairs (Penrose stairs). On the steps, two queues of figures are walking in opposite directions. However, despite the fact that the figures are constantly moving, they are neither going up nor down. They are trapped in this endless, hopeless loop, unable to reach their destination. The image may be a metaphor for human society repeating the cycle of war and tragedies again and again.

In an interview given eight years later, Escher said, “I’m not sure what to do with reality, my work has nothing to do with it. I know it’s wrong. I know it is your duty to help, to help it all turn for the better. But I am not interested in humanity.”[21] In Ascending and Descending, aside from the walking figures on the roof, there are two figures located at opposite sides of the lower levels of the building. One figure is looking at the people on the roof, while the other figure is deep in thought. In Escher’s “impossible architecture” prints, occasionally the viewer can see characters observing some kind of puzzles. These characters possibly serve as the artist’s self-projection. Such examples include the boy playing with the puzzle in Belvedere (1958) and the man looking at the towers in Waterfall (1961) (fig. 5). In Ascending and Descending, the “observers” are the two lone figures on the lower levels, seemingly reflecting Escher’s own confusion of reality, disappointment with humanity, and guilt of not knowing how to help direct society in a better direction, despite his growing fame as a graphic artist.

Following the end of World War II, Escher turned from depicting real-life scenes to creating imaginary worlds. Working on such a subject was possibly a coping method for the artist to escape from the harsh and traumatizing reality that he disliked and feared. By isolating himself in his studio, he enjoyed the impossible, but rational and stable, world he constructed through imagination.

Themes of Illness and Death

Struggling with health issues throughout his life, world wars, and the deadly pandemic of 1918, Escher was not unfamiliar with illness and death. All these experiences seemed to ignite the artist’s interest in themes of death and loss. In 1932, Escher created a lithograph of the mummified priests in the catacombs of the Madri di Gangi church (fig. 9). At the sight of the church, there were many framed texts hanging next to the priests’ bodies, narrating the life stories of the priests. However, in the finished print, Escher removed the frames, leaving only the bodies behind. Below the priests, the artist added a line of text: “Ite, missa est,” the dismissal formula addressed to people at the end of the Mass of the Roman Rite.

Fig. 9. M.C. Escher, Mummified Priests in Gangi, Sicily, lithograph, June 1932

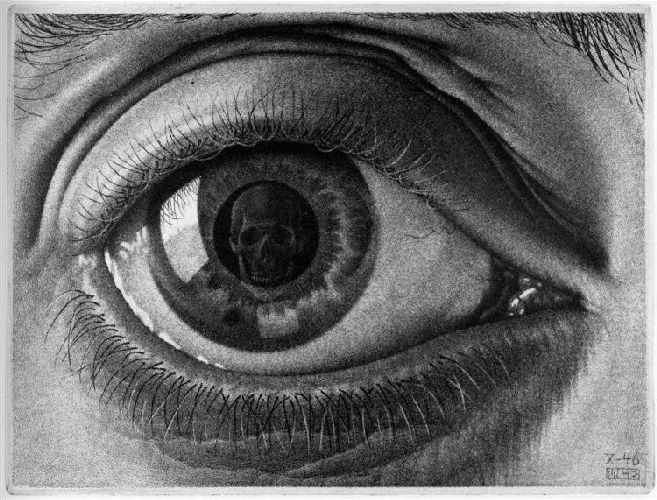

In 1946, one year after the end of World War II, Escher made two pieces of unsettling mezzotint prints titled, Mummified Frog and Eye (fig. 10), possibly as a reflection of the deaths he witnessed during the war. The first piece was created after a real mummified frog was found behind a piece of furniture in his own house. Just as he captured the scene of the priests fourteen years ago, the artist depicted the frog the way it was discovered.[22]

Fig. 10. M.C. Escher, Eye, mezzotint, October 1946

In the second print, Eye, a skull is reflected in the pupil of an eye. This is Escher’s own eye studied through a convex shaving mirror. Shortly after the creation of this piece, the artist wrote to a friend, “As the viewer always sees himself in the eye he is looking into, I decided to show a skull reflected in it. As a variant on the prints with reflective spheres. Because we are all forced to look at Death, whether we like it or not. Or He looks at us.”[23] This artwork may be a continuation of a series of three prints of skulls he made from 1917 to 1921.

By using the motifs of the skull and mummified bodies, Escher represented death. The featured objects are used as Memento Mori (Latin for 'remember that you have to die,’ referring to a symbolic reminder of a human’s inevitable death in artwork). The skulls and remains of once alive bodies are used to remind the audience and Escher himself of the powerful and indifferent existence of death.

Conclusion

Escher’s life experience generated a huge influence on the content of his artworks. The artist’s personal life, emotions, and worldviews are deeply integrated into the design of his artworks. From the often tense and changing relationship with family members, to the awareness of the inevitability of death, Escher’s work records the ups and downs and reflected the happiness and sadness of his life. There are many more personal self-expressions presented in these artworks than the artist gave himself credit, and Escher deserves to be respected more as a great artist.

[1] Elisabeth Maria Lampe-Soutberg, “Bibeb interviews Escher: ‘I think what I make myself the most beautiful and also the ugliest’.” Bibeb. Translated by Google. Vrij Nederland, April 18, 1968. Accessed November 7, 2020. https://www.vn.nl/bibeb-escher/

[2] “Timeline.” Escher in Het Paleis. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.escherinhetpaleis.nl/about-escher/timeline/?lang=en

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Biography.” M.C. Escher Collection. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://mcescher.com/about/biography/

[6] Lampe-Soutberg, “Bibeb interviews Escher.”

[7] “Portrait of Father Escher, 1935.” Escher in Het Paleis (August 25, 2018). Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.escherinhetpaleis.nl/escher-today/portrait-father-escher-1935/?lang=en

[8] Filiz Efe McKinney, Uriah McKinney, and Aaron Sarnat, “The House of Four Winds.” Brave Sprout Productions in association with the M.C. Escher Foundation. Video. 2015. Accessed November 7, 2020. https://vimeo.com/142037451

[9] Lampe-Soutberg, “Bibeb interviews Escher.”

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Jan Bosdriesz, “Metamorphose: M.C. Escher, 1898-1972.” Cinemedia, Nederlandse Programma Stichting (NPS), Radio Netherlands Television. Video. 1999. Accessed November 7, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g4VAxilTRGs&t=1907s

[13] “The OMG Moment of Waterfall.” Escher in Het Paleis (October 12, 2019). Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.escherinhetpaleis.nl/escher-today/waterfall/?lang=en

[14] “Timeline.” Escher in Het Paleis.

[15] Bosdriesz, “Metamorphose: M.C. Escher, 1898-1972.”

[16] Lampe-Soutberg, “Bibeb interviews Escher.”

[17] “The ‘Kultuurkamer’.” Escher in Het Paleis (January 5, 2019). Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.escherinhetpaleis.nl/escher-today/the-kultuurkamer/?lang=en

[18] Lampe-Soutberg, “Bibeb interviews Escher.”

[19] Ibid.

[20] Bosdriesz, “Metamorphose: M.C. Escher, 1898-1972.”

[21] Lampe-Soutberg, “Bibeb interviews Escher.”

[22] “Mummified Frog.” Escher in Het Paleis (August 4, 2017). Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.escherinhetpaleis.nl/escher-today/mummified-frog/?lang=en

[23] “Eye.” Escher in Het Paleis (October 26, 2019). Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.escherinhetpaleis.nl/escher-today/eye/?lang=en