Known as the father of political cartoons, no other artist wielded more power in influencing public opinion of the American political scene than Thomas Nast during the 19th century. Thomas Nast was born in Germany, and his family moved to New York City around the time he was six. In 1855, Nast landed his first illustration job at Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. After a few years, in 1862 he moved on to join Harper’s Weekly, one of the most widely circulated magazines in the United States during his time.[1] Nast worked for the publication as an artist for the next twenty-five years, and it is within those years he rose to prominence as a political cartoonist. As the most recognizable figure of Harper’s Weekly, Nast won the popularity of an extraordinarily vast audience through his “artistic talent, keen political perception, devastating satire, inventive genius, and unquenchable conviction.”[2] One of his most notable achievements during his career includes facilitating the dismantling of the notoriously corrupt Tweed Boss and Tammany Ring that swindled New York City of millions of dollars. However, towards the end of the 1870s, Nast’s popularity eventually waned and he was alienated at Harper & Brothers, the company that owned Harper's Weekly, due to a combination of political conflicts between him and the editor, cultural shifts towards civility among the American middle class, changing techniques in image productions in the publishing world, and his disappointment in the Republican party.

Even though Thomas Nast’s most successful works were published during his time working for Harper’s Weekly, what truly shaped him into a political cartoonist was his experience working at Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Here, young Nast not only honed his drawing abilities and artistic style, but he also became interested in politics. “Nast gravitated to politics not because he happened to have worked as a political illustrator; he worked as a political illustrator because he was drawn to politics.”[3] Nast was merely fifteen when he joined Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper as a staff artist and was constantly surrounded by a team of artists, illustrators, engravers, and journalists who produced content that reflected a wide range of political events, issues, and ideas of the day—from common problems of street maintenance and dangerous vehicles to immigration rights and police corruption. At Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, illustration and journalism were not distinctly separated, and the mixture of art and reporting created a sense of urgency and purpose, which was endorsed by the founder, Frank Leslie. He wrote, “An illustrated newspaper, if it fulfills its mission, must have its employees under constant excitement. There can be no indolence or ease about such an establishment. Every day brings its allotted and Herculean task, and night affords no respite.”[4]

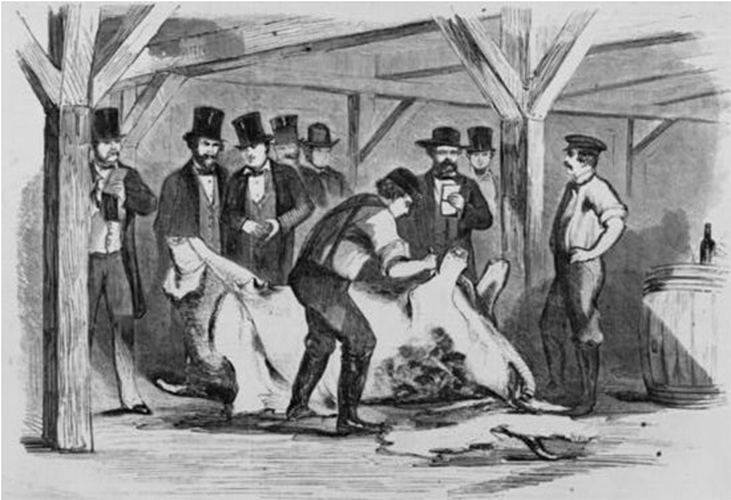

Fig. 1. Thomas Nast, Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper’s investigations on swill milk led to a nation-wide scandal, published on May 13, 1858.

Thomas Nast was also involved in the thick of action during his time working at Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. His most important assignment was to lead the attack on the swill milk scandal. In the 1850s, the corrupt city officials of New York protected the action of selling polluted milk from diseased cows who were milked in filthy stalls; the milk was mixed with plaster, starch, and eggs.[5] Nast was one of the artists who was sent by Leslie to draw illustrations that reflected the horrendous conditions of the barns (fig. 1). After receiving death threats and facing immense obstacles, Leslie’s persistence eventually led to a bitter, fierce, and successful campaign. This was Nast’s first encounter with a corrupt city government, and he learned the power of his political cartoons. It is at Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper where Nast built his foundations and found his mission of being a social crusader, which was consistently reflected in his works throughout his career.

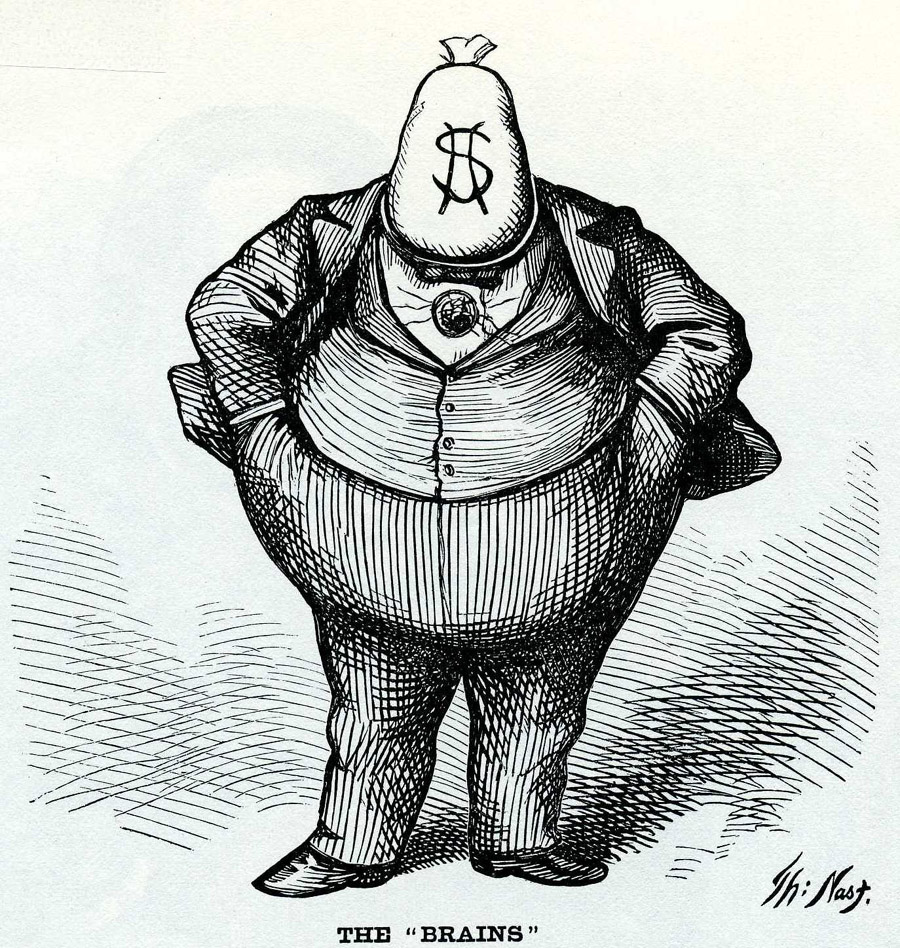

Thomas Nast had found a desire to express his political viewpoints and sway the public. Besides having a strong motivation, his strategy of using effective visual tactics and his ability to engage and provoke his audience is what established him as a successful political cartoonist. “He not only enthralled a vast audience with boldness and wit, but swayed it time and again to his personal position on the strength of his visual imagination.”[6] Nast sustained a profound impact on the public; people not only enjoyed his drawings for entertainment, but saw them as a source of direction. “Let’s wait and see what Tommy Nast says about it”[7] shows people’s respect for his insight. During the course of his career, Thomas Nast turned political cartooning into a respected and powerful journalistic form. Nast’s success could not be achieved without adapting to a straightforward and bold drawing style, simplifying complex political subjects into a matter of good versus evil that was easily understood by a broad audience. He also mastered the use of visual metaphors and recognizable and memorable symbols such as the Republican elephant and the dollar sign as a “graphic evocation of greed and surplus wealth”[8] (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Thomas Nast, The "BRAINS" that achieved the Tammany victory at the Rochester Democratic Convention, 1871. Boss Tweed is represented as having a money-bag face. Another identifying feature is the $15,500 diamond stickpin.

Nast’s famous confrontation against the notoriously corrupt William M. Tweed, who was the “boss” of the Tammany Ring, proves the power of persuasive imagery. The Tammany Ring was the main political machine of the Democratic Party, and played a major role in controlling politics in New York City and New York State. Tweed and his Tammany Ring directed local services, controlled elections, received millions of dollars in bribes, and stole immense amounts of money from tax revenue. Contrary to Tweed, Nast was an idealist and patriot who favored the new Republican Party. He embraced the Emancipation Proclamation, Abraham Lincoln, and Ulysses S. Grant.[9] There was no doubt that Boss Tweed and the Tammany Ring would be a target of Nast’s pencil. Nast created a series of political cartoons that captured the hypocrisy and greed of Tweed and Tammany using graphic forms and symbolism that communicated his ideas without the need for captions.

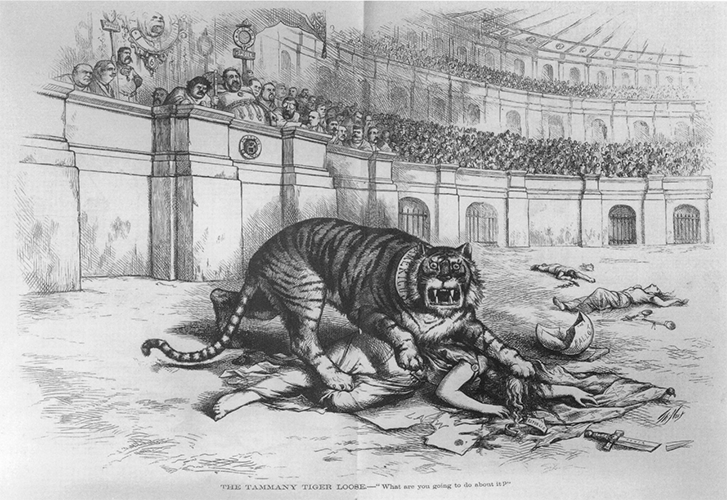

Fig. 3. Thomas Nast, The Tammany Tiger Loose. “What Are You Going to Do About It?,” Harper’s Weekly, Vol. 15, November 11, 1871.

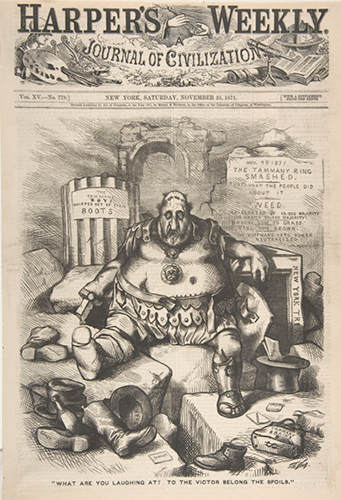

In the cartoon titled The Tammany Tiger Let Loose (fig. 3), which was published right before the election, Nast intensified the accusation against the Tammany Ring through the depiction of the savage Tammany Tiger. In this drawing, Nast “cast the female allegorical symbol of Liberty as a Christian martyr, mauled by the Tammany Tiger in a Roman amphitheater dominated by Boss Tweed enthroned as emperor.”[10] Before being knocked to the ground by the tiger, the woman had been wearing a crown labeled “Republic” and carried a sword labeled “power.” She lies defeated on top of a ripped paper that notes “Law,” and further in the background the “Ballot” is shattered. The audience watching the battle carries a sign that reads “Tammany Spoils.” The inhumane cruelty and savageness of Tammany Hall became fully visible in Nast’s image. The tiger he drew here has a frightening expression with his jaw wide open, it is no cartoon feline but an entirely plausible predator.[11] Even the illiterate could not fail to grasp his message: letting the Tammany Tiger loose in the arena is a disastrous situation to the American democracy and the people of New York. This piece served as a final blow towards Tweed and Tammany; it was likened to a destructive missile, “a pictorial projectile so terrific in its power, so far-reaching in its results, that Ring rule and plunder the world over shall never cease to hear the echo of its fall.”[12] Nast’s crusade against Tammany and Tweed made himself a household name and “catapulted him into the forefront of his profession, and he became a national celebrity and sought-after companion in powerful New York and Washington political circles.”[13] The rage he sparked in the public achieved substantial victory—many government officials with ties to the Tammany Ring were voted out of office and Tweed himself was thrown into jail. In What Are You Laughing At? To the Victor Belong the Spoils (fig. 4), Nast celebrates the defeat of his target by portraying Tweed as Caius Marius, who was the former consul of Rome exiled to the ruined city of Carthage. In the image, Tweed wears a crown of dollar signs but is surrounded by the boots of his beaten allies voted out of office. The treasure Tweed sits on is empty and his sword is broken, symbolizing the end of Tweed’s political and financial power.

Fig. 4. Thomas Nast, What Are You Laughing At? To the Victor Belong the Spoils, Harper's Weekly, November 25, 1871.

Despite Nast’s success during the 1870s, he inevitably fell from favor while still a young man. The rapid changes in the publishing world and the political scene did not sit well with Nast and he struggled to maintain his past glory. As new technology made color printing cheaper and faster, Nast was forced to change his artistic technique as Harper’s Weekly switched from producing images using wood engraving to photo-chemical engraving. He was forced to change his solid cross-hatching lines made on engraver’s wood and use pen and ink on paper, which negatively affected his ability to create intense characters.[14]

Besides technical difficulties, Nast also struggled with the visual language of his personal style. He used to work under Fletcher Harper who supported his style of not afraid of being bold by making use of violence and savagery. However, when George William Curtis took over as the editor, he “frequently implored Nast to be less cruel and uncompromising in his characterization.”[15] The problem did not lie between diverging core political opinions between the two, but rather how to set the tone for political debate. For example, they had different attitudes towards critiquing the Republican Party. “While Curt mildly critiqued Republican politicians or possible allies, Nast brazenly criticized them.”[16] Curtis’s preference was aligned with a cultural shift in America that occurred in the 1880s. The middle class now had a “renewed interest in civility and gentility” to which Nast failed to adapt. Magazines like Harper’s Weekly were caught between two different publishing realms—newspapers and books. Newspapers were often more accessible to the raw market, the language and imagery are more likely to be associated with bias and savagery, while books represented a more polite and civilized version of culture and history. During the Civil War years, Nast’s cartoons were well-received because they reflected a turbulent political scene filled with conflicts. As the American public transitioned out of those years, they began to prefer less of Nast’s violent style. To remain a popular publication, Harper’s Weekly attempted to appeal to the new desires of its readers, which was not in line with Nast’s intentions.[17] He expressed his opinion in a quote, “I cannot do it. I cannot outrage my convictions.”[18]

Another personal political dilemma Nast underwent was his torn opinion towards the Repulican Party itself and the candidates that now represented the party. In the 1880 election, James Abram Garfield became the Repulican candidate. Nast did not favor him because of Garfield’s involvement in the Crédit Mobilier scandal and less radical position towards Reconstruction. On the other hand, the Democratic Party nominated Winfield Scott Hancock as its candidate. Hancock was a close friend of Nast, someone who Nast respected and admired. At one point, Nast drafted a cartoon that endorsed Hancock by saying that the Democrats had finally chosen a great candidate, though the cartoon was rejected by Harper’s Weekly. Nast eventually gave in by making cartoons that attacked the Democratic Party in general, but not Hancock as a person.[19] However, this was not the end of Nast’s conflict with the new Republican Party, but was later intensified in his opposition against Republican candidate James G. Blaine.

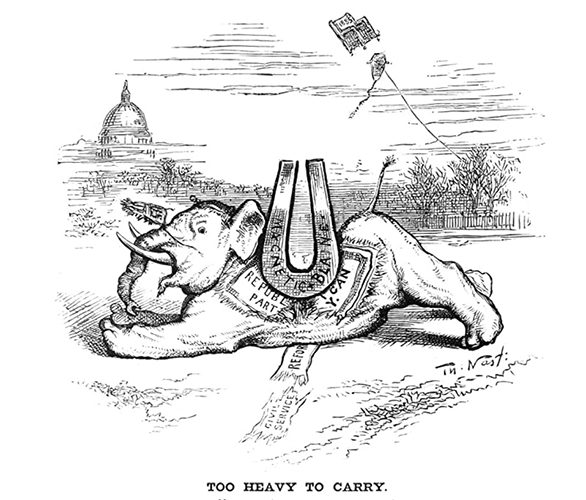

Fig. 5. Thomas Nast, Too Heavy to Carry, 1884. Thomas Nast illustrating the heavy burden of the James G. Blaine candidacy on the Republican party.

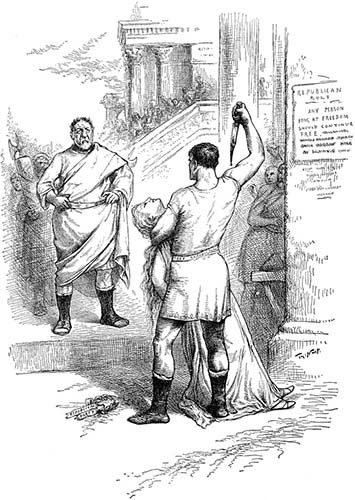

None of the obstacles that hindered Nast’s career dealt more damage than his harsh rejection towards Blaine. He first depicted Blaine as a burden to the Republican Party in Too Heavy to Carry (fig. 5) where Blaine is represented by a magnet that crushes the Republican elephant and tainting the sacred purity that the part animal represents. Nast later ruthlessly opposed Blaine in Death Before Dishonor (fig. 6) by referencing Virginius’s death before the corrupt ruler Appois Claudius tainted her purity. The man killing the virgin is wearing a belt that says “Free Republican,” which suggests that the Republican Party should abandon Blaine before he ruins the value the party stands by. Nast’s stab at the Republican Party attracted bitter complaints. “In Judge, a bit of verse summed up the reaction: Poor, poor T. Nast/ Thy day is past—/ Thy bolt is shot, thy die is cast-/ Thy pencil point is out of joint/ Thy pictures lately disappoint.”[20] The opposition to Blaine was a costly step for Nast, Curtis, and Harper's Weekly. Even though Nast saw success in Blaine’s defeat in the presidential election, the journal suffered critical financial loss and never recovered fully, as did Nast’s career. “Harpers lost its Republican base as a consequence, and subscriptions plummeted.”[21] Nast eventually left Harper’s Weekly and both he and the paper suffered by the end of their relationship. “In quitting Harper's Weekly, Nast lost his forum; in losing him, Harper's Weekly lost its political importance.”[22]

Fig. 6. Thomas Nast, Death Before Dishonor Virginius “On thee and on thy head be this blood,” Harper's Weekly, June 21, 1884.

Even though Thomas Nast eventually faded out of popularity, the legacy he left behind is impossible to ignore. During his own days, he not only acted as the pictorial advocator but also contributed to the development of political cartooning in America. The power of his imagery is proved in his success of swaying public opinion, most notably is his achievement in defeating the Tammany Ring and Boss Tweed. The symbols and imagery he created such as the dollar sign and the Republican elephant have become an unforgettable element of the American culture. Most importantly, Nast has set a precedent for other artists who wish to use their artistic talent as a tool to advocate. If used efficiently, pictures can prove to be more powerful than words.

[1] Baird Jarman, “The Graphic Art of Thomas Nast: Politics and Propriety in Postbellum Publishing,” American Periodicals 20, no. 2 (2010): 156-189.

[2] John Chalmers Vinson, “Thomas Nast and the American Political Scene,” American Quarterly 9, no.3 (1957): 337-44.

[3] Fiona Deans Halloran, Thomas Nast The Father of Modern Political Cartoons (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 57.

[4] Halloran, Thomas Nast The Father of Modern Political Cartoons, 25.

[5] Thomas Nast and John Chalmers Vinson, Thomas Nast, Political Cartoonist (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1967), 3.

[6] Albert Boime, “Thomas Nast and French Art,” American Art Journal (1972): 43-65.

[7] Nast and Vinson, Thomas Nast, Political Cartoonist, 1.

[8] Boime, “Thomas Nast and French Art.”

[9] Halloran, Thomas Nast The Father of Modern Political Cartoons.

[10] Vinson, “Thomas Nast and the American Political Scene.”

[11] Sarah Burns, “Party Animals: Thomas Nast, William Holbrook Beard, and the Bears of Wall Street,” American Art Journal (1999): 8-35.

[12] Vinson, “Thomas Nast and the American Political Scene.”

[13] Brooke Speer Orr, “Crusading Cartoonist: Thomas Nast,” Reviews in American History (2014): 291-295.

[14] Vinson, “Thomas Nast and the American Political Scene.”

[15] Ibid.

[16] Jarman, “The Graphic Art of Thomas Nast: Politics and Propriety in Postbellum Publishing.”

[17] Ibid.

[18] Halloran, Thomas Nast The Father of Modern Political Cartoons, 221.

[19] Ibid., 248.

[20] Ibid., 261.

[21] Tom Culbertson, “Illustrated Essay: The Golden Age of American Political Cartoons,” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era (2008): 276-295.

[22] Vinson, “Thomas Nast and the American Political Scene.”