Illustration (detail) above: Standard Of Ur. Sumerian commemorative mosaic, 2550 B.C.

The word Mesopotamia means “Land Between Two Rivers” (the Tigris and Euphrates), where several city-states formed in what is now Iraq and Iran. Home to the Sumerians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, the region was a vast and fertile flood plain that encouraged agriculture and domestication of animals and helped to establish self-supporting societies. The cultivation of grasses having seeds that could be ground into flour led to a renewable—and tradable—food source that improved the health of the collective. Similarly, ancient Egyptian society developed as a result of the rich soil of the Nile flood plain. Regional cultures competed, fought, cooperated in trade, and evolved independent artistic styles.

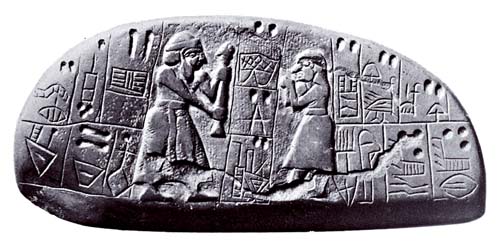

Blau Monument, Mesopotamia, 3000 B.C.

Image making and writing were formal activities conducted by an elite caste of artisans and scribes who were employed to portray the events and affairs of royal life and honor the reigns and achievements of its leaders through writing, illustration, and portraiture. Illustration with accompanying text (cuneiform, hieroglyphics) was considered an important element of monumental architecture as well as of small, commemorative plaques. It was integrated into religion and burial, used to honor military campaigns, used in business documentation and depicted the lives, activities, and entertainments of royalty. Images represented kings conducting affairs of state, hunting and fishing, and being honored with gifts, and queens attended by servants and dancers.

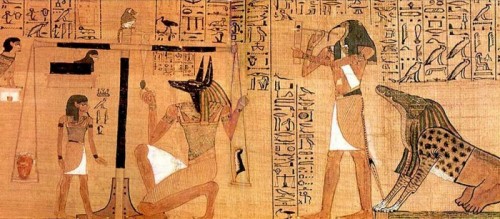

Book of the Dead, Egyptian scroll, Papyrus of Ani, 1420 B.C.

Matters of life and death, magic, mythology, law, science, and the attributes of gods were described through both writing and art together in a confluence of word and image that was more complete than either would be alone. Books of the Dead, for example, were necessary documents that were created—for a fee—by craftsmen to portray in formal text and pictures the worthiness of a particular soul to pass into an afterlife.

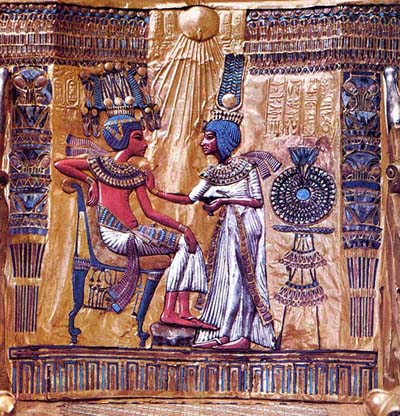

Throne of King Tut (detail), 1350 B.C.

In Egyptian culture, painting became more than an embellishment for sculpted reliefs or a substitute for stone carvings. Art was a visual equal of the tactile and real world. Representational illusionism was employed to show translucent garments and objects in space. Beauty was described through the depiction of makeup and personal ornament, as well as through the elegance of form and pose. Specific localities were represented—gardens, docks, warehouses, and palaces. Illustration could be seen everywhere in royal courts, on furnishings, plaques, and wall paintings. Art reflected earthly life and the afterlife and through symbolism, scale, and composition provided a framework for understanding culture. Without illustration, our knowledge of the ancient world would be sparse and incomplete.

Assyrian wall relief (detail), palace of King Ashurbanipal, ca.630 B.C.