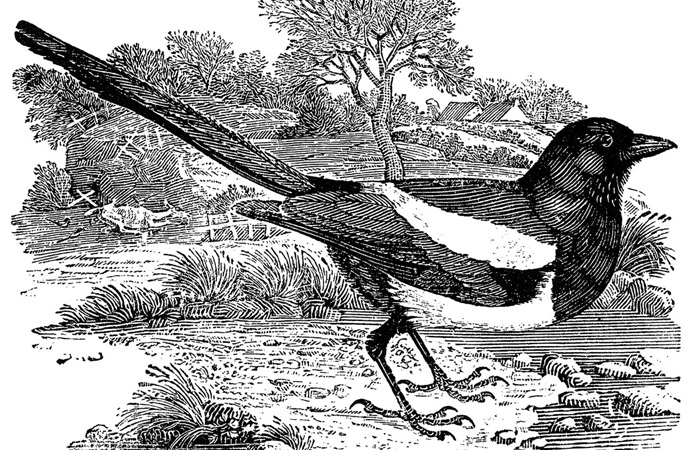

Illustration (detail) above: Thomas Bewick, wood engraving, "The Magpie," ca.1790s

The Industrial Revolution began in the mid-1700s, marking the change from an agricultural society to an industrial one. A factory system of machines creating products was established, and towns expanded to surround the new manufacturing buildings. Masses of people left the meager existence of farm life to seek employment in the cities, and political power shifted away from the aristocracy and landowners towards merchants, manufacturers, and capitalists. A middle class arose quickly and in large numbers—especially in England. Workers in the factories advanced to become managers who sought better lives, better housing, and more schooling for their children. Consequently, literacy rose and the demand for books, magazines, and newspapers increased, because the new middle class wanted to read about current events affecting their lives and jobs, and also wanted to be entertained and enlightened.

With increased demand for reading material, production was stimulated and printing technology improved to meet the demand, resulting in more publications being distributed and seen. Illustration became more commonly encountered in daily life—typically as etchings or copper engravings which were inserted into books, or as woodcuts or wood engravings which would be used in mass-produced publications.

Thomas Bewick, Little Tommy Trip, 1779

English wood engraver and publisher Thomas Bewick established a studio in the 1780s solely for the creation and printing of commercial illustration. His wood engravings were intended for many purposes and covered subjects like sports, outdoor activities, music, the arts, and natural history. They ranged from large, full-page illustrations for books to small decorative cuts intended for educational primers, children's stories, title pages, and flyers.

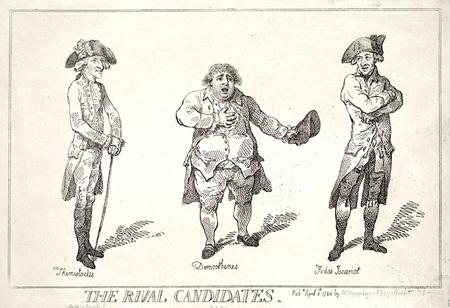

The gradually industrializing cities of Europe were ever noisier and more crowded and social classes collided on a daily basis. Art and literature of this period focused on social conditions through cautionary tales and satire. William Hogarth’s work in the early 1700s was pivotal in establishing the tradition of the mass-produced popular print that carried a moral or social message. Satirical drawing, caricature, and the political cartoon were popular items for purchase from print shops and street stalls because people enjoyed seeing their own opinions on social and political subjects confirmed through art.

Thomas Rowlandson, political candidates, 1784

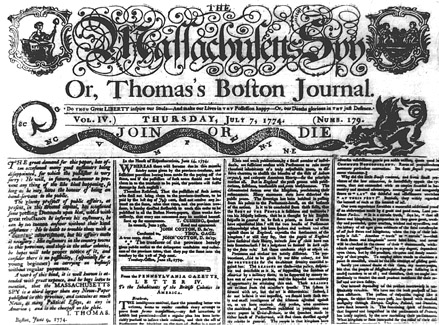

The Massachusetts Sun, 1774

Newspaper publishing spread throughout Europe and the Americas and often utilized woodcuts or wood engravings to embellish the front-page masthead. American engravers and printmakers attempted to produce well-crafted images, but their skills could not compare to the classically trained artists of Europe like Charles-Nicolas Cochin, whose parents were both life-long engravers in Paris.

Etched and engraved print, "A New Method of Macarony Making as Practiced at Boston" (man being tarred and feathered), ca.1775

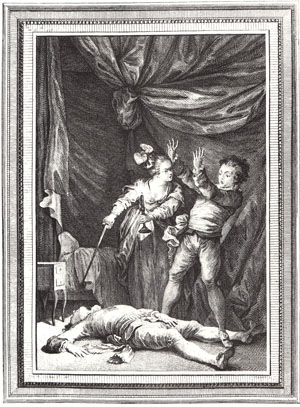

Charles-Nicolas Cochin, book illustration, "Gabrina and Filandro," Roland Furieux, ca.1780