Illustration (detail) above: Simon Bening, hand painted plate in prayer book, 1500s

The Renaissance was a period in Western Europe when there was a rebirth of the classical Roman and Greek belief in the spirit of the individual man—humanism.

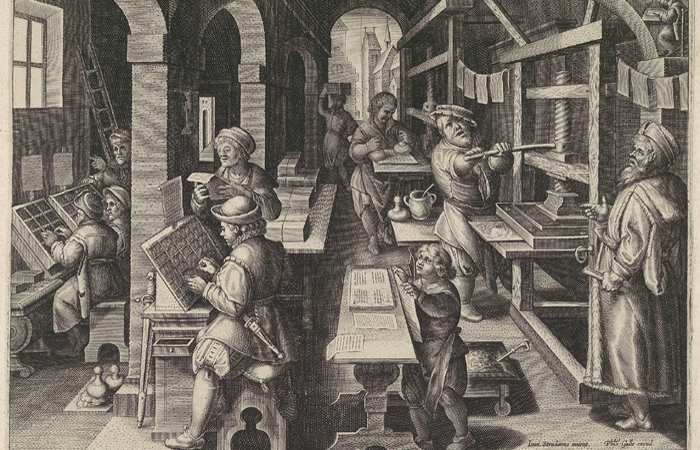

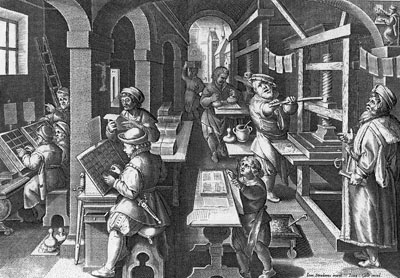

It marked the advance of a cultural sophistication that was gradually beginning to coexist and even compete with the dominant tenets of Christian life that defined the Middle Ages. There was new music, literature, art, and printed books, which could be mass produced and distributed due to the perfection of a mechanical process by Johannes Gutenberg and his workshop in 1452. The creation and distribution of publications that used woodcuts and engraved prints along with typesetting brought images and ideas to a wide audience. With inexpensive woodcut devotional or decorative prints being sold, it became possible for even ordinary people to experience art. Printing technology spread from Germany to the rest of Europe and then the world in a very short time.

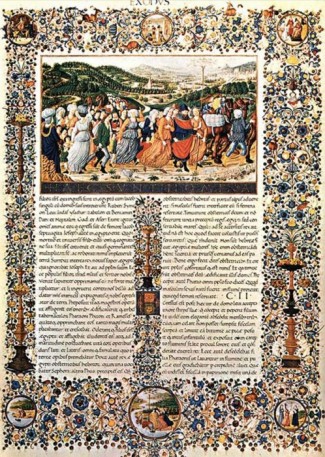

Urbino bible, poss. illuminated by Davide and Domenico Ghirlandaio, among others, 1478

Print shop, engraved print, ca.1500s

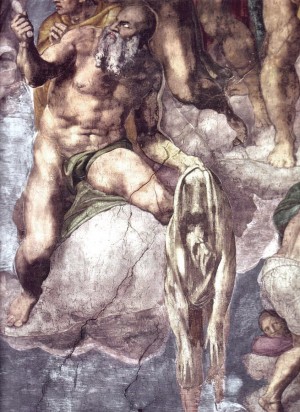

Michelangelo Buonarotti, The Last Judgement, panel (detail) from the Sistine Chapel, 1512

Artists were trained from an early age by masters and grew in capability while working as apprentices on commissioned projects. Some, like Botticelli (and Giotto before him), would become leaders of successful, independent studios. Throughout the Middle Ages and into the central period of the Renaissance, there was no difference seen between picture-making and any other craft or skill. Michelangelo and most others performed commissions that were essentially illustrative (and often, narrative) in nature and served government, business, the royal courts, or the clergy. Like today's illustrators, artists of the Renaissance worked with clients and had to seek approval for their designs, state the costs of materials, and sign contracts agreeing to all of the conditions and fees.

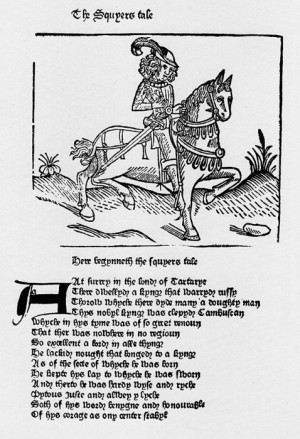

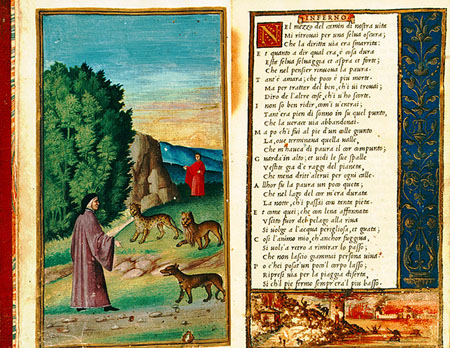

In the later Renaissance, distinctions began to be made between "fine art” and craft. The magnificence of the artworks being created for the church by Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael were truly inspiring in both technique and effect. The skills of these artists elevated them above ordinary craftsmen, and they were seen to have divine gifts. Patrons sought out great artists because their works brought status to the person, church, or ruler and inspiration to the viewer. Magnificent achievements like the Urbino bible, illustrated by Davide and Domenico Ghirlandaio, among others, were hand-calligraphed, but in the late Renaissance hand painting might be applied to typeset books that could be manufactured. The Italian printer Aldus Manutius published Dante's Inferno in 1508 to which illustrations were added. The English printer, William Caxton, produced the first printing of Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales.

Canterbury Tales, printed by William Caxton, 1484

Illuminated Dante's Inferno, printed by Aldus Manutius, 1508

Strong and stable governments allowed for improved trade that added to the wealth of monarchies and financed colonial expansion. Navies were built to protect shipping, and expeditions were sent out to locate the best and fastest routes for reaching new trading partners. The Renaissance roughly coincides with the beginnings of Europe’s Age of Exploration, and when ships were sent on a mission, artists accompanied them to record and illustrate what was encountered. Jacques Le Moyne, John White, and others, made drawings and small watercolor paintings of animals, plants, and the human populations. When the ships returned, the drawings were exhibited, replicated by engravers, printed, and bound into folios or published as books for sale to collectors.

Jacques Le Moyne, ca.1560s, engraved prints by the publisher de Bry, ca.1590