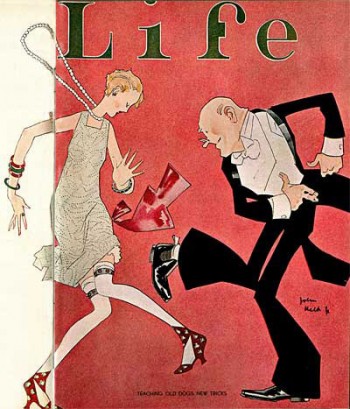

Illustration (detail) above: John Held Jr.

The end of the First World War brought prosperity as well as great social change, and America became the economic and political powerhouse of the world. Soldiers returned to a confident country, eager for jobs, family, and friends. Women had been granted the right to vote. College education was more common and could lead women to professional careers. America began to set the trends and tastes for world-wide popular culture and faced the first large "generation gap." The social freedoms that were now possible for America's young people separated them entirely from their Victorian-era parents. They dressed differently, had new forms of music and dancing, and exhibited a libertarian morality. The publishing, advertising, and entertainment industries catered to this age group and made twenty-somethings and their current styles the focus of the culture.

John Held, Jr., Life magazine cover, 1926

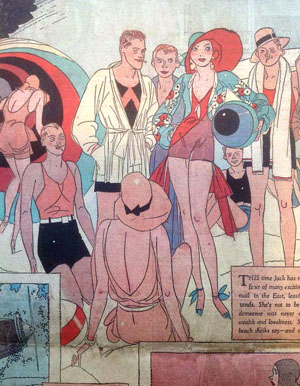

Russell Patterson, newspaper panel page, 1929

American magazine illustrators had been, for the most part, portraying literal reality, but in this decade a shift began: stylized illustration was becoming a dominant trend. Earlier, Maxfield Parrish, J.C. Leyendecker, and Rose O'Neill had developed stylized characterizations, but in the 1920s John Held Jr., like no other artist before him, used an abstract cartooning and comic illustration approach to capture the essence of a whole young generation. His thin, angular girls with long legs, short skirts, and pouty lips were cute and provocative—and the symbols of social revolution. Russell Patterson portrayed upper-class characters from the same generation in drawings and comic panel pages, and Henry Patrick Raleigh’s narrative scenes of drama and romance were populated by tall, elegant figures that were the precursors of modern fashion illustration.

Henry Raleigh, magazine illustration

Narrative realism in the Brandywine tradition continued with the paintings of Dean Cornwell, a student of one of Howard Pyle’s pupils, Harvey Dunn. Cornwell was one of the great masters of illustration, considered even by his contemporaries as without peer. His technique ranged from spontaneous brushwork to high realism, and he created pictures for all the major magazines, worked on advertising campaigns, and produced a strong body of mural work.

Dean Cornwell, magazine illustration, 1923

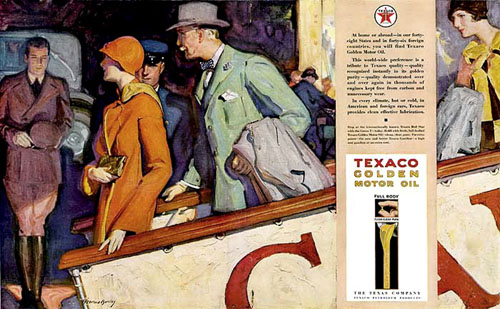

Advertising agencies began to take on a powerful role in setting cultural trends. Ad agency art directors could commission illustration that rivaled publication work in quality and technique, while paying much higher fees to artists. Ads could portray everything from realistic situations to comedy, and illustrators used to narrative were given the chance to make personal interpretations of advertising concepts (McClelland Barclay).

McClelland Barclay, advertising illustration, 1929

In general, illustration had become a highly paid field for the very top artists, and their lifestyles reflected that with grand estates, chauffeured limousines, and live-in chefs. Illustrators socialized with literary and entertainment industry stars, and female illustrators—like actresses in the movie business—began to achieve personal successes that rivaled men's. After many commissions for humor publications like Puck and Life and early success at the turn of the century and 1910s, Rose O’Neill became a millionaire in the late 1920s and 1930s through the merchandising of her Kewpie characters and dolls. Neysa McMein, a women’s rights activist and friend of writers and playwrights, was one of the earliest and most successful female advertising illustrators. She was best known for her many McCall’s magazine covers that featured women in society.

Rose O'Neill, self-portrait with Kewpies

Neysa McMein, advertising illustration

Norman Rockwell's long career was solidly underway in the 1920s with The Saturday Evening Post covers that portrayed American character types in captured moments of ordinary life. Rockwell achieved a connection to his viewers because his characterizations reminded them of things they'd seen or felt or done themselves. They displayed ordinary human qualities, were rarely handsome or beautiful, and were exaggerated just enough to draw attention to their expressions, body language, and interactions with each other so that the scene and characters could be quickly understood. Rockwell produced art for people to relate to.

Norman Rockwell, cover illustration, The Saturday Evening Post, 1921