Illustration (detail) above: Stevan Dohanos

When America entered the European war against Hitler's Nazi Germany and began to defend against Japan’s thrust into the Pacific in 1941, Europeans had already been embattled for four years and news of the war had spread around the world. In a time before television, people relied on newspapers, radio, and documentary “newsreels” in movie theaters for information about current events. Although, these media rarely captured the human side of war. For that, people turned to movies, but also to the magazines where illustrated stories brought to life the drama of both military and civilian wartime situations (Stevan Dohanos). Illustrators also found work creating propaganda posters that were intended to raise spirits, summon support for the war effort, and encourage the conservation of resources (Dean Cornwell).

Dean Cornwell, promotional ad, U.S. Government bonds

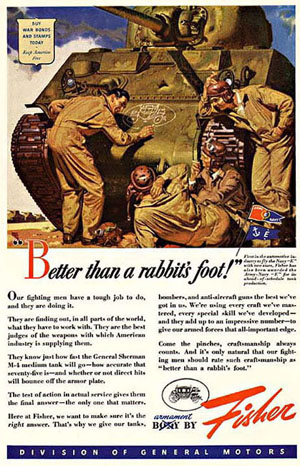

Illustrated advertisement for Fisher. Artist unknown.

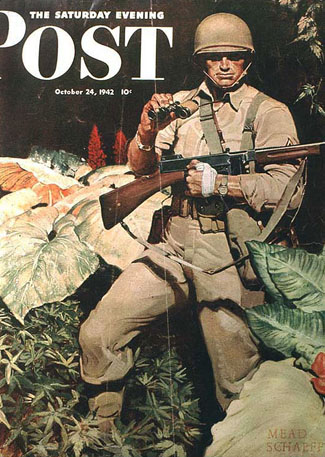

In advertising, illustrators were assigned to show the positive and patriotic roles of companies whose production had shifted into making war materials. For example, the Fisher company, supplier of the structural frames for General Motors cars, had, throughout the 1930s, become known for an ad campaign called "Body by Fisher"—a tag line that led to a visual pun in a campaign that featured a beautiful woman illustrated by McClelland Barclay. In wartime, the Fisher company made frames for tanks instead of automobiles and trucks and used illustration to show their products in war service. Saul Tepper and other seasoned illustrators were called upon to paint action scenes for magazine fiction. The Saturday Evening Post covers shifted away from light-hearted scenes to portraying more iconic American values and patriotism, and to military personnel performing their service (Mead Schaeffer).

Saul Tepper, magazine illustration

Mead Schaeffer, magazine cover, The Saturday Evening Post, 1942

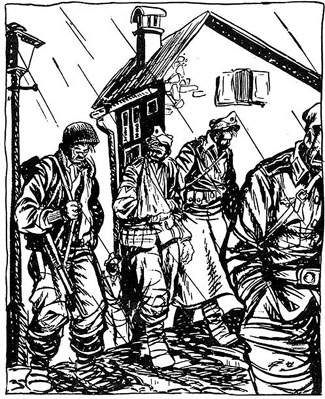

Bill Mauldin, cartoon, Stars and Stripes, 1944

Drafted or enlisted, artists entered the war. Some, like Howard Brodie, recorded in sketchbooks what they observed in battle. Others worked in the press corps or for military publications. Most popular among servicemen were cartoons by Bill Mauldin for Stars and Stripes, the Armed Forces newspaper. Mauldin was assigned to their offices in Washington D.C. for a short time but was transferred to the infantry as it cleared a path through Italy. Cartooning every day with brush and ink, he portrayed his main characters, Willie and Joe, as ordinary guys just trying to make the best of bad situations. After the war Mauldin continued his career, becoming a Pulitzer Prize winning political cartoonist.

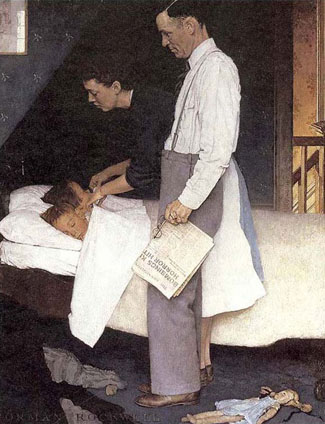

Norman Rockwell's Four Freedoms paintings—based on a speech made by President Roosevelt and published by The Saturday Evening Post—were a patriotic inspiration and a phenomenal success. After their publication, the Post received 25,000 requests for reprints. In May 1943, representatives from the magazine and the U.S. Department of the Treasury announced a joint campaign to sell war bonds and stamps. They would send the Four Freedoms paintings, along with 1,000 original cartoons and paintings by other illustrators and original manuscripts from the Post, on a national tour. Traveling to sixteen cities, the exhibition was visited by more than a million people, who purchased $133,000,000 in war bonds and stamps. Bonds were sold in denominations of $25, $100, and $1,000, and each person who purchased one received a set of prints of the four paintings. In addition, the Office of War Information printed four million sets of posters of the paintings. Each was printed with the words “Buy War Bonds.” They were distributed in United States schools and institutions and overseas.

Norman Rockwell, Freedom from Fear, 1943

Wartime was a time of mixed messages for women. The entertainment media portrayed them as glamorized sexual objects or dutiful wives, but many enlisted into the military to work as nurses or served as hostesses in the service clubs. Factories rapidly turning out war materials needed workers, and women took up the jobs for which men were no longer available. Norman Rockwell portrayed "Rosie the Riveter," a mythologized shipyard worker based on a real person, and the character became a symbol for womens' contributions to the war effort.

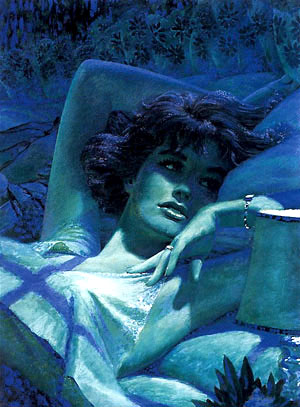

The 1940s brought a new genre of film making called film noir, with its use of strong lighting and dark shadows to create brooding scenes of lust, deceit, and murder. Magazines published fiction of the same kind, along with romance, intrigue, and wartime adventure. Illustrators were influenced by the filmmakers' approaches to lighting and composition (Edwin Georgi). Also, as movie theaters all over America projected close-up images of beautiful actresses onto big, bright screens, advertisers and art directors asked for illustrations that featured the same thing. Magazine editors demanded art that showcased the female, even if she were only a minor character in a story, and publications were filled with pretty faces and emotionless characters.

Edwin Georgi

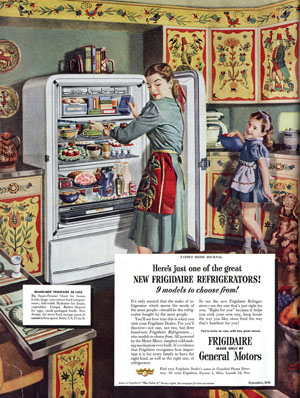

Returning servicemen were welcomed back into the workplace and the women who occupied their jobs were sent home. With a government benefits program called the G.I. Bill, veterans qualified for free college tuition or financial aid for vocational training. Many used their government benefits for art school training and then found jobs at the agencies and art studios. Vets could also get mortgages for new homes at a low 3% interest rate. The government subsidized real estate developers to build housing just beyond the city limits, and suburban life began. Every veteran who wanted to could have the American Dream: their own little house with a white picket fence, a good job, and a wife devoted to staying at home and raising a family. The post-war baby boom began. In the increasingly prosperous economy and with a ready market for goods, manufacturers already geared into high production during the war began churning out products again. Advertising agencies loaded magazines and newspapers with their clients' product advertising, and the homes in a newly suburban America filled up with the latest in housewares, labor-saving devices, bikes and cars, as well as fresh and processed foods bought from the well-stocked new, supermarkets.

Albert Dorne, advertising illustration, 1948