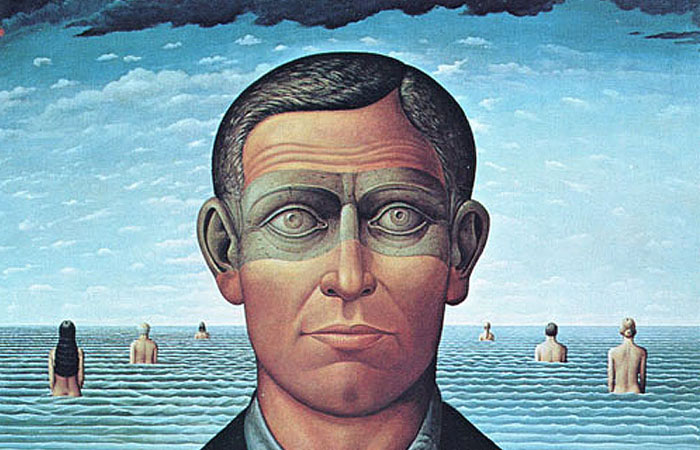

Illustration (detail) above: "Memory" by Richard Hess

In the second half of the 20th Century, America's expanded middle-class consumer society demanded entertainment, and all media were growing exponentially. The music, movie, and publishing industries were becoming stronger than ever. The post-war generation began their professional careers, and those interested in art and design had many kinds of employment opportunities in publishing, advertising, and with corporations—from insurance companies to fashion houses.

The Society of Illustrators in New York City, formed at the beginning of the 20th Century as an elite men’s club, is an important professional organization which sponsors public exhibitions of the best contemporary and historic original illustration art. The annual juried competition is open to any practicing illustrator, from well-established pros, to up-and-coming young artists doing their first work. At "the Society" original works of illustration art were being exhibited regularly in the 1970s and were being seen by larger numbers of people, especially students of illustration at art schools. Also, examples of award-winning published work were being shown in the trade magazines and provided young artists with inspiration to enter the field.

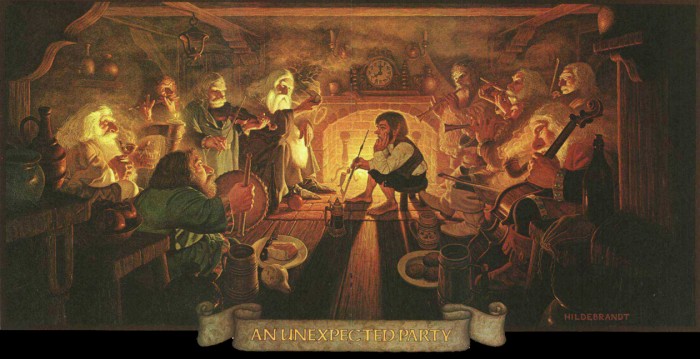

Tim and Greg Hildebrandt, Tolkien Calendar, 1978

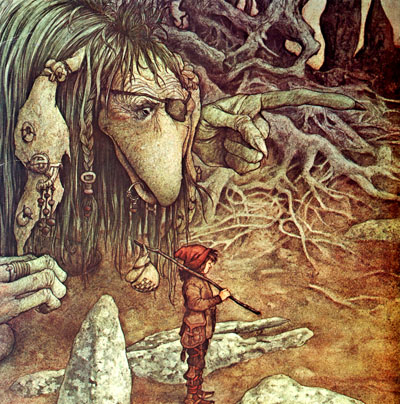

The publishing of J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings in the mid-1950s led fantasy literature to be reborn after a long sleep—since Victorian England’s love of fantasy and the freshly retold and illustrated fairy tales of the early 20th Century. The long-established genre of science fiction often included fantasy tales, but it wasn't until the late 1960s that young people fully latched on to reading about fully developed fictional worlds like Tolkien’s "middle-earth" and the imagined histories of medieval-inspired cultures populated with wizards, dragons, knights and princesses, trolls, goblins, elves, fairies, and unicorns. Writers began to generate fantasy novels, which were treated with beautifully illustrated covers. Jim Henson's studio in the early 1980s produced very popular fantasy films like The Dark Crystal, which benefitted from character drawings by artists who specialized in fantasy, like Brian Froud, himself influenced by Arthur Rackham and the Swedish artist John Bauer. In 1972 the film, Star Wars, brought together familiar worlds of medieval-like cultures, gave them advanced technologies, and pitted their knights against militant cultures bent on universal domination. The film's combination of science fiction and fantasy was irresistible and its advanced production techniques, model making, animatronic figures, painted scenic, and adventure plot line made it immensely popular with the public and a broad influence to writers and artists. Teams of illustrators helped the director to visualize the characters and sets with their drawings, enlarging what had previously been a small sub-field for artists: character and scenic design for films. This grew to become today's "concept art," which is a major area of interest and opportunity for illustrators.

Fantasy games began as an outgrowth of the fantasy movement in popular culture. With illustrated board games, role-playing fantasy card games, video games, and then—with the development of the personal computer—computer games, there was a range of new media requiring illustration. This expanded the employment opportunities of illustrators who no longer had to rely solely on the publishing industry's books and magazines for commissions.

Brian Froud, The Dark Crystal

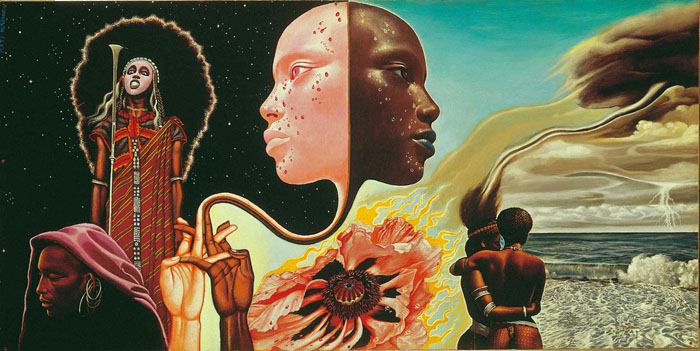

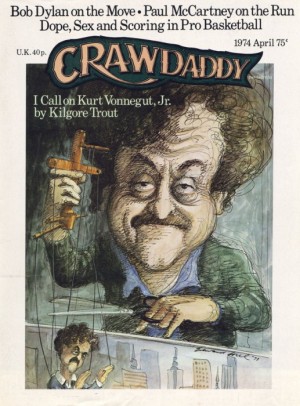

The recording industry grew in the 1970s, and illustrated album covers provided a dynamic twelve-by-twelve inch format for illustration. Mati Klarwein’s two-panel, two foot wide fold-out cover painting for Miles Davis’ album, Bitches Brew, changed the way that people thought of album art. Music magazines took a firm hold, with Rolling Stone and Crawdaddy leading the field and hiring illustrators to portray musicians, writers, entertainers, and political personalities, generating a revived interest in and enjoyment of caricature and celebrity portrait illustration. Playboy and other men's magazines commissioned the top illustrators of the day for the short fiction they published, attracting international artists to their pages. Illustrators from England, France, Germany, and Eastern Europe were being commissioned by American art directors. Magazines were published in international versions exposing more people than ever to illustration of all kinds and styles.

Mati Klarwein, album art, Bitches Brew, 1970

Edward Sorel, Crawdaddy magazine, 1974

With the post-war generation beginning to raise families, there was also an increase in books published for children, especially "picture books," where the story is brief with its words carefully designed and where the illustrations provide a world for the child to enter and enjoy. The masterful Maurice Sendak, Alice and Martin Provensen, and Eric Carle were joined by a host of new artists entering that field including Swiss-born Etienne Delessert.

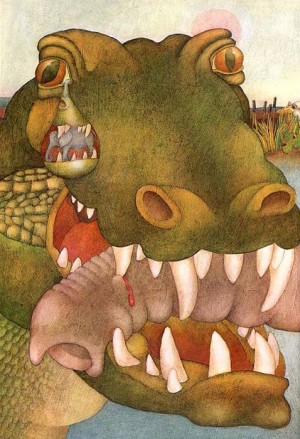

Etienne Delessert, Just So Stories by Rudyard Kipling, 1972

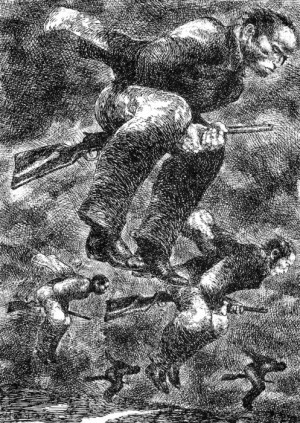

The New York Times made a bold move to bring illustration to its editorial pages. Other papers used political cartoons, but the Times either commissioned or bought conceptual illustration, meant to illustrate the ideas and opinions of its "Op-Ed" page articles and letters as in the illustration below by Brad Holland. Using metaphor, allusion, and symbolism, this art led readers to think more deeply about political and social issues.

Brad Holland, The New York Times, "Firing Squad"

Under all of these influences young artists wanted more than ever to become illustrators, and art schools were ready to oblige them with training. There were numerous ones to choose from and a variety of approaches to education that might suit their needs—private art schools, art colleges, part-time evening programs in Continuing Education with a selection of courses in illustration, and even full illustration programs leading to BFAs—with most courses being taught by working professionals sharing their knowledge and experience. Parsons School of Design, the School of Visual Arts, and Pratt Institute in New York City all had full or part-time illustration programs, as did other schools around the country, like the Rhode Island School of Design, Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, the Art Institute of Boston, and the Philadelphia College of Art.