Illustration (detail) above: "Crusader Bible," 1240 A.D.

The Middle Ages were a critically important period for Western Europe. The preceding “Dark Ages,” which lasted for hundreds of years after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, had been a time of chaos and poverty without strong central government to maintain order. During the period, Roman roads and water distribution systems decayed. Farming and mining all but ceased entirely. Travel was dangerous and trade routes were unused. Birth rates dropped, and disease and infections decimated undernourished human and animal populations. Western art and culture were virtually non-existent except for what was protected by Christian monks and missionaries. The clergy held fast to the traditions of reading, writing, manuscript illumination, and panel painting in order to maintain the Christian faith. Monasteries were the only remaining centers of cultural, educational, and intellectual activity, and consequently they were targets for looting. In Ireland, successive Viking and Norse invasions forced the removal of treasured books from their original locations so that they could be protected and hidden. A few surviving texts, such as the Book of Durrow, the Lindesfarne Gospels and the Book of Kells are wondrous examples of Christian art and craft.

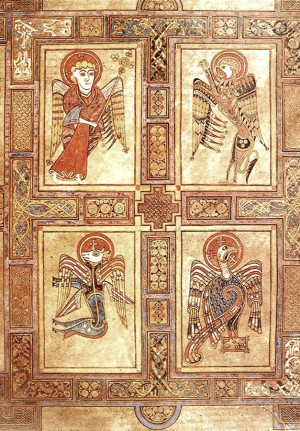

Illuminated page from the Book of Kells, "Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John," 800 A.D.

Light began to enter the Dark Ages in the late 700s, when Charlemagne, the son of a powerful warlord controlling vast lands in what is now Germany, France, Austria, Hungary, and the Netherlands, became the leader of the Franks, the largest tribe in Europe. He and his family engaged in decades of military incursions and conquests to acquire territory, and established a strong central government along with a stabilizing control structure—a feudal system—which protected the poorest of citizens through regional land-lords with private militias. This government united most of Western Europe for the first time since the fall of the Roman Empire.

In 800 A.D. Pope Leo, seeing an opportunity to reinstate a Western Church, made Charlemagne Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. But Charlemagne's goals went beyond political position. Although unable to read and write himself, he valued culture and began a series of efforts to foster it. Monk-scribes and lay craftsmen were imported into the West from the Eastern Roman Empire and began to create books. Scholars helped to establish standards for writing in Latin so that it could become the unifying formal language of the realm. New "Carolingian" art revived Roman realism and combined it with contemporary stylization. For all this, Charlemagne (Charles the Great) would be called "the Father of Europe." One of the most beautiful works of this Carolingian period was a Gospel book created by the monk Godescalc—an extraordinary example of craft, art, calligraphy, and language.

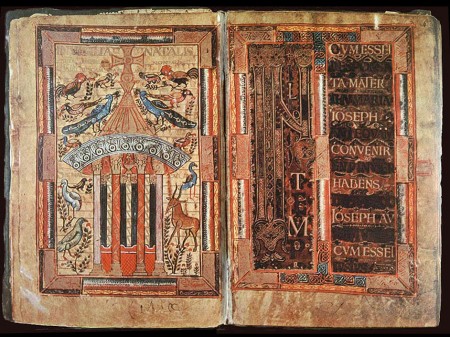

Godescalc Gospels, Carolingian illuminated book (reign of Charlemagne), 782 A.D.

International trade began again in Europe during this time. Culture grew, and by the 1200s art was no longer the sole realm of the Christian clergy. Artisans formed craft guilds, opened workshops, and sought commissions from the Church, government, the nobility, and the increasingly wealthy merchant class to create frescoes, panel paintings, and illuminated prayer books. One early remarkable example is the illuminated book called the Crusader Bible (Morgan Bible) which was created in Northern France in 1240 and features action scenes complete with battle wounds being inflicted, and detailed realism including specific types of weapons, spurs, armor, and other actual garments.

When the Black Plague struck in 1348-1350, much of what had been gained was in danger of being forever lost again when one-third of Europe’s population died. However, wealth became more consolidated in the hands of fewer families, and after recovery from the ravages of the disease there was a return to patronage of the arts—ultimately sewing the seeds for the coming Renaissance.

Illumination showing mass burial of plague victims, 1349

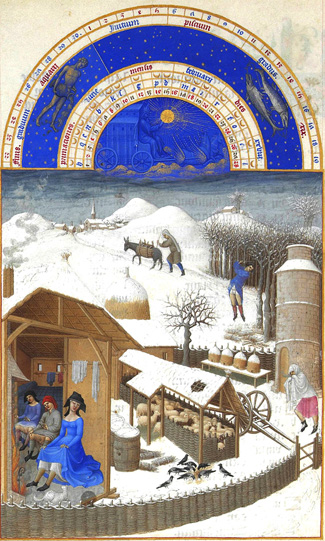

Prominent, wealthy patrons commissioned beautifully bound illustrated books as personal luxury possessions. The value of one book might be equal to that of a farm or vineyard because of the cost of materials and salary to the artists. The late 1300s and early 1400s were the great age of the illuminated book and the small, painted illustrations of Jean Pucell, Jean Fouquet and the Limbourg Brothers from that period showed extraordinary skill and accomplishment. Realism became a dominant approach to painting and the Limbourgs showed things never before rendered, like shadows, woodsmoke, and the steaming exhalation of breath on a cold day. This art rivalled anything being done in panel painting and frescoe, and all of it was illustrative.

The Limbourg Brothers, calendar page "February," Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1415

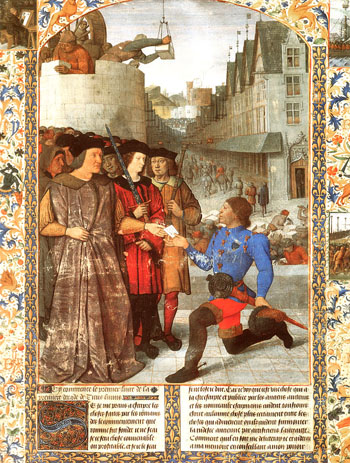

Jean Fouquet, illumination, Chevalier Hours, 1453